I used to dislike Ernest Hemingway’s style. His iceberg technique, with so much left beneath the surface, seemed cold in contrast to the sonatas of his contemporaries like F. Scott Fitzgerald. In a letter containing advice to the latter author, Hemingway admitted as much. “I write one page of masterpiece to ninety-one pages of shit. I try to put the shit in the wastebasket,” Papa wrote. “You feel you have to publish crap to make money to live and let live.”

That was Hemingway’s gentle approach to telling a friend to get out of his own way and write.

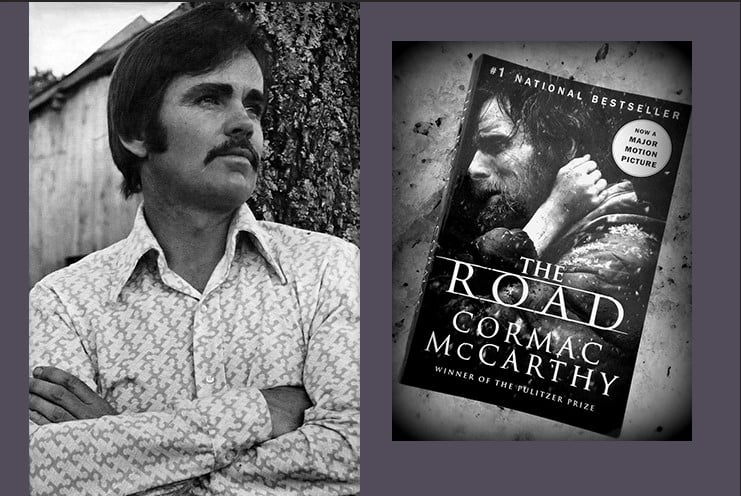

However I have a renewed appreciation for Hemingway, who is one of the most appropriate stylists for the moment. My reassessment began with Cormac McCarthy, who, as novelist Alan Bilton put it, owed a “formal debt” to Hemingway. McCarthy helped me to understand what Hemingway was trying to do and why, because he did it better. Author Peter Josyph submitted that “in All the Pretty Horses, McCarthy is Hemingway: he is what Hemingway would have been had he lived to be Cormac McCarthy.”

If you have read The Road, you have suffered through McCarthy’s most emotionally searing work. If you haven’t, without spoiling anything, it’s a story about a father and son struggling to survive after the world has ended. Bands of roving marauders rape, kill, and cannibalize the few men, women, and children yet alive. The Earth itself seems to be slowly dying as it drifts through the indifferent void of space after an extinction event has precluded the possibility of a future. McCarthy provides clues but never tells you what exactly happened. You only know that attempting to stay alive under these conditions is absurd, and yet that is what the father endeavors to do on behalf and only because of his son, his “world entire.”

No other book has affected me as much as The Road, which I read shortly after becoming a father. It was at once difficult to put down and to pick up. The narrative is a relentlessly hopeless odyssey into the darkest parts of the human psyche. And yet, it is also profoundly tender. The father and son are a single beating heart wrapped in the rags of a world that no longer exists and never will again. They have nothing but each other amid implacable misery.

McCarthy conveys all these feelings in his distinctive, spare, brutal prose that is also found in his other novels, such as Blood Meridian. He does not tell you how the characters feel; he makes you feel how they do. Nothing is “given” to the reader, who is made to suffer alongside the man and the boy.

There is something unique about The Road. McCarthy’s ability to make the reader feel what his characters are feeling almost seems like sorcery until you learn, as I later did, that the book was inspired by McCarthy having a son late in life against the odds of biology. It is easy to see, then, how McCarthy was inspired to write about a man struggling to care for a young child in a perilous world. McCarthy’s unnamed protagonist is a stand-in for every father raising a child in precarious times.

In a roundabout way, I could appreciate Hemingway more in this light. After all, Hemingway’s style was really a product of the trauma of World War I. In the words of Henry James, war had “used up words, they have weakened, they have deteriorated like motor car tires.” Hemingway reproduced that line from James in an unpublished manuscript of A Farewell to Arms. It’s a paradox that one of the greatest shapers of American literary style believed that words are, to some extent, useless. And he was right.

Words have never been more “used up” than they are today. They have never been cheaper, hollower. But that’s why I think Hemingway is fit for the moment and why those he inspired, like McCarthy, are experiencing a resurgence of interest. People do not want to read words that do not correspond with anything real. They want to feel.

Leave a Reply