From the December 2014 issue of Chronicles.

It has been argued that, after Shakespeare, Charles Dickens is the finest writer in the English language. His works have forged their way into the canon to such a degree that it is much more difficult to know which of his novels to leave off the recommended reading list than it is to choose which to include. Each of us has his favorites, and each begs to differ with his neighbor’s choice. True, in terms of pure brute statistics, we would be forced to concede that A Tale of Two Cities is preferred by most people, because it is usually listed as the bestselling novel of all time, with sales exceeding 200 million. (Don Quixote, which is excluded from official statistics and has never been out of print since its first publication 400 years ago, has probably sold more copies.)

Those justifiably skeptical of the claim that the bestselling is necessarily the best might point to a poll conducted by the Folio Society, a de facto private club for bibliophiles, as a more objective way of judging the best of Dickens. More than 10,000 members of the society voted in 1998 for their favorite books from any age. The Lord of the Rings triumphed; Pride and Prejudice was runner-up; and David Copperfield was third. Why, one wonders, was this particular Dickens classic selected ahead of Nicholas Nickleby, Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, and Bleak House? It’s a mystery as insoluble as that surrounding Edwin Drood in Dickens’ last, unfinished work.

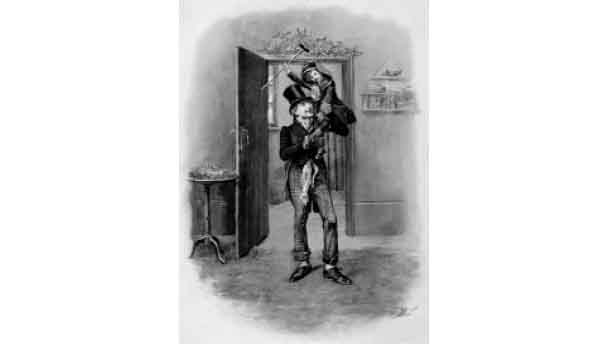

Yet none of these Dickensian heavyweights wins my vote, which belongs to A Christmas Carol, a diminutive volume that not only punches above its weight but outpunches its heavyweight rivals. Originally published in 1843, A Christmas Carol is sandwiched chronologically between the larger tomes Barnaby Rudge and Martin Chuzzlewit. But the character of Ebenezer Scrooge is a literary colossus who, without the benefit of eponymous billing, has emerged from Dickens’ imaginary menagerie as a cautionary icon of mean-spirited worldliness. Serving as a “mirror of scorn and pity towards Man”—among the qualities Tolkien considered to be the chief characteristics of all good fairy stories—Scrooge has shone across the generations as a beacon of hope and redemption, as powerful parabolically as the Prodigal Son, of which he is a type.

The story begins with the cold hard fact that Jacob Marley is “as dead as a door-nail”:

There is no doubt that Marley was dead. This must be distinctly understood, or nothing wonderful can come of the story I am going to relate. If we were not perfectly convinced that Hamlet’s Father died before the play began, there would be nothing more remarkable in his taking a stroll at night, in an easterly wind, upon his own ramparts, than there would be in any other middle-aged gentleman rashly turning out after dark in a breezy spot . . . literally to astonish his son’s weak mind.

The connection with Hamlet at the very beginning of the novella has a deep significance that the whimsical tone should not obscure. In Shakespeare’s play as in Dickens’ story, the ghosts serve to introduce not merely a supernatural dimension to the work but a supernatural perception of reality. The ghosts reveal what is hidden to mortal eyes; they see more. They serve as supernatural messengers who reveal crimes that would otherwise have remained hidden. Their intervention is necessary for reality to be seen and understood and for justice to be done. Thus, in connecting Marley’s ghost to the ghost of Hamlet’s father, Dickens is indicating the role and purpose of the ghosts that he will introduce to Scrooge, and to us. They will show us ourselves in a manner that has the power to surprise us out of our own worldliness and to open us to the spiritual realities that we are prone to forget.

It is, however, not only the ghosts who teach us timely and timeless lessons but our mortal neighbors. The first visitors that Scrooge receives are not ghosts but men. His nephew waxes lyrical on what might be termed the magic or miracle of Christmas:

I have always thought of Christmas time, when it has come round—apart from the veneration due to its sacred name and origin, if anything belonging to it can be apart from that—as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys.

There is no need to remind Scrooge’s nephew of the necessity of keeping Christ in Christmas! He knows that it is venerated because of its sacred name, and because of its sacred origin in the birth of the Savior. How can anything associated with Christmas be separated from its sacred source and purpose? The very thought, as expressed by the nephew, is plainly absurd. Scrooge does not disagree. He has no intention of celebrating the feast while ignoring its sacred name and origin, as do most people in our own hedonistic times. After complaining that his nephew should let him keep Christmas in his own way, the nephew reminds him that he doesn’t keep it at all. “Let me leave it alone, then,” Scrooge replies.

Another essential facet of the nephew’s defense of Christmas is his reminder to his uncle that the poor and destitute are “fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys.” This is not merely a memento mori but a reminder that we are not homo sapiens, smug in the presumption of our cleverness, but homo viator, creatures or “passengers” along the journey of life, the only purpose of which is to get to Heaven. Furthermore, our fellow travelers, made in God’s image, are our mystical equals, irrespective of their social or economic status. They are not “another race of creatures bound on other journeys” but our very kith and kin bound on the same journey of life. And we cannot reach the destination that is the very purpose of life’s journey without helping our fellow travelers get there with us. A Christmas Carol shows that our lives are not owned by us but are owed to Another to Whom the debt must be paid in the currency of self-sacrifice, which is love’s means of exchange.

The book operates, as might be expected of a meditation on the spirit of Christmas, most profoundly on the level of theology.

Marley’s ghost, like the ghost of Hamlet’s father, is a soul in Purgatory and not one of the damned. This is obvious from its expressed desire to save Scrooge from following in its folly-laden footsteps. When Scrooge seeks to console Marley with the reminder that he had always been “a good man of business,” the ghost appears to be flummoxed:

“Business!” cried the Ghost, wringing its hands again. “Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

If Marley’s ghost is the spirit of a mortal man, suffering penitentially and purgatorially for its sins, the Ghosts of Christmases Past, Present, and Yet To Come are best thought of as angels, divine messengers. More specifically, they might be seen as Scrooge’s own guardian angels: The first specter describes himself as being not the Ghost of Long Past but that of Scrooge’s own past.

Finally, A Christmas Carol celebrates life in general, and the lives of large families in particular. The burgeoning family of Bob Cratchit, in spite of its poverty—or, dare we say, because of it—is the very hearth and home from which the warmth of life and love glows through the pages of Dickens’ story. At the very heart of that hearth and home is the blessed life of the disabled child, Tiny Tim, which shines forth in the child’s love for others and in his family’s love for him. His very presence is the light of caritas that brings Scrooge to his senses. After his conversion, Scrooge no longer sees the poor and disabled as being surplus to the needs of the population, mere indigents who should be allowed to die, as in our own day they are routinely killed or culled in the womb; he discovers that they are a blessing to be cherished and praised. For this love of life, even of the life of the disabled—especially of the life of the disabled—is at the heart of everyone who knows the true spirit of Christmas as exemplified in the helplessness of the Babe of Bethlehem.

Leave a Reply