“Render to all what is due them,” writes Saint Paul, “Tax to whom tax is due, custom to whom custom; fear to whom fear; honor to whom honor” (Romans 13:7, NASB). When a zealous Christian offered to help Mark Twain understand the difficult things in the Bible, Twain said something like this: “It is not the things I don’t understand that bother me, but those that I do understand.” In the United States of the 21st century, we understand tax only too well, alas, and we understand custom—or at least we used to in the days before globalization. We certainly understand fear: fear of terrorists, on the one hand, and, less plausibly, of right-wing Christian extremists, on the other. But honor? Probably Twain understood that particular concept, but it seems to have dropped out of our minds even as it has almost disappeared from our vocabulary.

In earlier ages, honor was an item so precious to men that many a man challenged an opponent who had insulted him even when he knew his adversary to be a better swordsman or pistol shot. For many, “Death before dishonor” was not an empty slogan but an inflexible rule of life—and death. Better to die on the field of honor than to live without honor. From a Christian point of view, dueling with deadly weapons has always been wrong, but honor was so highly prized that many Christians fought anyway, hoping to be forgiven afterward.

Today, honor as an ideal has almost vanished. When President Clinton’s trysts with Monica Lewinsky first became a national or even worldwide sensation, I, for a few days, expected him to slink out of sight. If a man of honor had made a speech honoring Strom Thurmond on his 100th birthday and was sharply criticized by the politically correct for it, he would have preserved his honor by responding, “I have honored an old friend; if you are offended, that is your problem.” Instead, Sen. Trent Lott abased himself, offering concessions to his detractors in an effort to preserve his status as Senate majority leader. Perhaps it was this self-humiliation, with its attendant loss of honor, that cost him the honorable post that he sought thereby to keep.

Political leaders, from town mayors to the president, have the prefix Honorable attached to their names. It once meant something, for, in theory at least, no one could rise to such eminence without being a man of personal honor. For many today, it means little, and with some, it must be seen as mocking. Would that it were not so. Would that the men and women thus called honorable felt themselves bound by the title to speak and act honorably and, if challenged, to fight for their honor—perhaps not with swords and pistols but with all the tools that unbloody rhetoric could supply.

The other title that once carried value and is now often seen as mocking is reverend. Not so long ago, it led those who bore it to act well and others to expect it of them. Florida drivers’ licenses used to identify the bearer’s profession—in my case, clergyman. When a highway patrolman stopped me for speeding (only moderately, be it said), he read “clergyman” and let me off with a warning: “Go and sin no more.” At the time, that was a witticism, for it was assumed that a minister in general avoided sinning even more scrupulously than ordinary Christians did. In his admonition to Timothy, Saint Paul tells him that a bishop (episkopos, overseer) must be “above reproach” (I Timothy 3:2). No man is totally above reproach, but the bishop was expected to make the effort; he was “to be the husband of one wife, temperate, prudent, hospitable, able to teach, not given to much wine or pugnacious, but gentle, uncontentious, free from the love of money.” Surely, anyone exhibiting all or even most of those qualities is to be revered, and with that reverence should come authority.

Those who are admired are easy to hear and easy to follow.

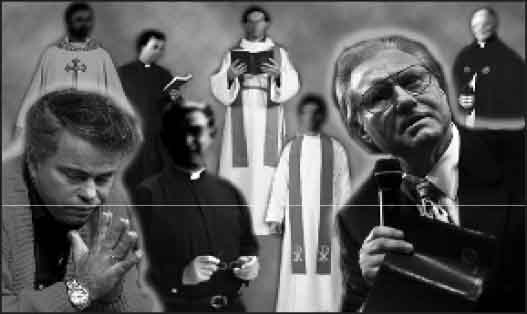

Political philosopher Hannah Arendt defines authority as the ability to elicit voluntary obedience. The man of honor is able to inspire followers in matters of civic life and conflict; the man who is justly called reverend will inspire imitators in matters of the spirit and faith. Today, as all-too-many honorables are without honor, too many reverends deserve no reverence. The political leader who lacks authority still has power that he can call upon to demand obedience, but the spiritual leader who deserves no reverence lacks power to compel and will have few followers. When many of those called reverend fail to live up to the Apostle’s instructions, the Church Herself loses respect and authority. Among Saint Paul’s standards, the one most frequently violated in Protestant circles is “free from the love of money.” Roman Catholics are used to having archbishops live in palaces, but, when a Protestant evangelist is seen to be using “the Lord’s money” as his own, it not only shatters respect for him but redounds to the harm of the Church and Her ministers in general.

In the mid 19th century, the Bernese pastor Jeremias Gott-helf (1797-1864) wrote, “Current politics are not directed only against the church, but at base against Christianity.” The disease that was beginning in Europe in the 19th century has taken on epidemic proportions there today, and here in the United States as well. The churches are under assault; Christianity itself is under assault. Viewed by the U.S. Supreme Court and found constitutionally wanting, Christianity sees both its strict and its lovable symbols (the Commandments and Manger scenes) banished from public view, its sacred texts and prayers banished from schools. Even more striking, the moral standards that have been with most of the Western world and, in spirit at least, with most of the rest of the world for centuries have become unutterable, being denounced as “intolerant,” “judgmental,” even “hate-filled.”

The Church is under terrific pressure from without, both from courts and governmental bodies and from the general culture. Taken as a whole, She is also constantly being sapped by treachery from within—by unorthodox, anti-Christian tendencies in doctrine and in life. Protestantism in the United States flows in many diverse streams. Some bodies, such as the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod, the Presbyterian Church in America, and the Anglican Mission in America, avoid contamination with doctrinal errors and moral deviancy, but the respect that they enjoy and the reverence in which their ministers are held is contaminated and diminished by their proximity to similarly named groups less committed to older standards of faith and morals. The Episcopal Church in America suffers from both doctrinal and moral erosion; a man (John Shelby Spong) who denies the truth of the bodily Resurrection of Christ can be a bishop, and so can one who abandons his wife to cohabit with a male paramour (V. Eugene Robinson). The presence in the Episcopal House of Bishops of someone who denies the Resurrection and of someone who breaks the marriage covenant to embrace a life contra naturam is trumpeted in the media, more often with glee than with reproach.

It is true that the most egregious examples of moral failings in Protestantism, both financial and sexual, have been seen in representatives of independent ministries, such as television evangelists. The most eminent of all American mass evangelists, the Rev. Billy Graham, however, is one whose consistent teaching and modest lifestyle really deserve the title “reverend.” Sadly, but naturally enough given the nature of the media, very little is said about his traditional doctrine or his financial integrity because they are not newsworthy, as that is the way he is supposed to believe and live. By contrast, the deviations of a Jim Bakker or a Jimmy Swaggart are broadcast all over America and the world. Thus, the more truly reverend individuals and fellowships also lose respect in the eyes of the general public.

This condition is virtually irremediable, because, between the fragmentation of the Christian community and the antagonism of most of the media, it has become virtually impossible for a church to discipline even the most egregious doctrinal or moral deviations. From the earliest days, Christian communities have been troubled with such problems, and, from the beginning, they have developed procedures to rid themselves of them and the persons causing them. Today, many church bodies have abandoned discipline altogether—sometimes because they lack the necessary convictions; sometimes because they are too timid to risk the disapproval of the media and the smirks of the unbelieving public. When a church is true to her confessions and foundational principles and seeks to discipline a minister or other officer, she will be called tyrannical, judgmental, obsolete, and probably overweight to boot. The substantial numbers of fellowships and of individual members who seek to remain true to their calling generally go unreported; and, when they are mentioned, they are treated as though they are in the same bucket with the doctrinally and morally deviant.

One rotten apple can ruin a barrel, and many good apples will not prevent it.

The loss of reverence for those with the title of reverend has gone so far that many clergy use it unwillingly, if at all. Today, it is probably fortunate that drivers’ licenses no longer identify the profession of the driver. If they did, patrolmen might be tempted to suspect a speeding clergyman of being on the way to an illicit sexual tryst with a call girl (or minor boy). No matter how many ministers, priests, superintendents, and bishops live unremarkably sober and righteous lives, the widely reported immorality of a few gives license to the general public to ignore the preaching of the many. When a letter to a newspaper is identified as being from a “reverend” of any kind, instead of carrying authority with readers, it is likely to be scrutinized for eccentric doctrines that will free readers from the obligation to believe or for evidence of the “judgmentalism” that automatically cancels any moral impact that the writer might hope to have.

In countries such as Germany and Switzerland, where the churches are partly supported by the state, there is far less possibility for priests and ministers to become rich through their ministries, and, consequently, their scandals, like much of their other entertainment, are imported from America. In Europe, the ministry and the churches suffer more from being ignored and treated as irrelevant, and the clergy are regarded more as expensive nuisances than as spiritual leaders who should be respected and followed. The title used for Roman Catholic priests in Austria, Hochwürden (High Dignities), is now perceived so much as a joke that few priests like to hear it used.

The zeal with which the media report transgressions by the clergy reached a high point in the exposure, denunciation, and even, one might say, celebration of the sexual abuse of children, mostly boys, and of homosexual adventures by Roman Catholic priests. Although the number of priests guilty of sexual abuse of minors represents a tiny segment of the total Catholic clergy, the shadow that it cast on priests made many reluctant to appear in public in clerical garb. As Pitirim Sorokin pointed out in The Crisis of Our Age (and I repeated in The Sensate Culture), the modern world has made a game of ridiculing and deriding, with or without real cause, those figures who, in past centuries, could be held up as ideals, from government leaders to Catholic priests. This is a variety of what Prof. Hans Millendorfer called societal AIDS. In medical AIDS, the virus destroys the T-4 helper cells that identify the aggressors so that the body’s defense mechanisms can attack them and prevent them from killing the body. In societal AIDS, the media, the entertainment world, and much of the academic community destroy the possibility that the clergy and religious leaders can be helper cells to identify the persons and forces that are killing society.

Leave a Reply