Now that a week has passed since Sen. John Sidney McCain III was given a truly presidential sendoff in Washington, it is not in poor form to try and amend the gushing record presented by the media and the bipartisan establishment. The plaudits and perorations are well known, including Meghan McCain’s amazing claim that America’s war in Vietnam was a noble fight “for the life and liberty of other peoples in other lands”; but now, audi alteram partem.

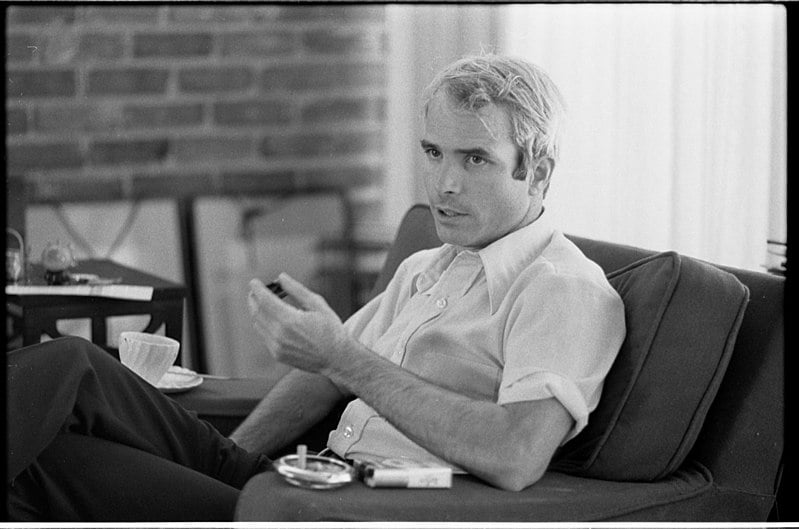

Following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, who both reached the rank of full admiral, McCain entered the US Naval Academy at Annapolis where he graduated 894th of 899. While there he earned the nickname “McNasty,” as well as hundreds of demerits every year—more than any other cadet. He was held in studied contempt by his superiors. It is well-nigh certain that he would not have graduated had it not been for his father’s rank and influence. At Pensacola, where he subsequently become a naval aviator, McCain gained a reputation as a man who partied a lot (in 1965 he married Carol Shepp, a model from Philadelphia) and who did not get on with his superiors. He was a sub-par flier, careless and reckless, prone to “push the envelope.” During the early 1960s, two of his flight missions crashed and a third collided with power lines in Spain, causing a massive regional outage. He lost four planes in all before finally being shot down over North Vietnam while bombing an electric bulb factory.

POW RECORD – As prisoner of war, McCain famously made an anti-U.S. propaganda confession in which he admitted being a war criminal for bombing civilian targets. He tried to justify it upon his release in 1973: “I had learned what we all learned over there: every man has his breaking point. I had reached mine.” But according to numerous sources—recently summarized in a long article by Ron Unz, publisher of The American Conservative—there was both more and less to McCain’s POW record than met the eye.

Unz recounts “shocking claims” made a decade ago that McCain may never have been tortured, and that he instead spent his wartime captivity collaborating with his captors and broadcasting Communist propaganda. Such doubts, Unz says, “were still in my mind a few months later when I stumbled upon Sidney Schanberg’s massively documented expose about McCain’s role in the POW/MIA cover up, a vastly greater scandal.” [Of that later.] He was subsequently given a first-hand account of McCain’s Hanoi record. It was hardly a secret in veterans’ circles, apparently, that McCain had spent much of the war producing Communist propaganda broadcasts, since these had regularly been played in the prisoner camps as a means of breaking the spirits of those American POWs who resisted collaboration. Indeed, former POWs had speculated about who possessed actual copies of McCain’s damning audio and video tapes, and wondered whether they might come out during the course of the presidential campaign.

Over the years, Unz pointed out, other Vietnam veterans have publicly leveled similar charges, and in late September 2008 another fascinating related story appeared in the New York Times. A reporter visited Vietnam to see what McCain’s former jailers thought of the possibility that their onetime captive might soon reach the White House, that the man they had spent years brutally torturing could become the next president of the United States:

To the journalist’s apparent amazement, the former jailers seemed enthusiastic about the prospects of a McCain victory, saying that they hoped he would win since they had become such good friends during the war and had worked so closely together . . . When asked about McCain’s claims of “cruel and sadistic” torture, the head of the guard unit dismissed those stories as being just the sort of total nonsense that politicians, whether in America or in Vietnam, must often spout in order to win popularity.

As for the famous photo showing McCain still on crutches even months after his release from captivity, in early September 2008 archival footage surfaced from a Swedish news crew which had filmed the return of the POWs, and uploaded it to YouTube. It shows a healthy-looking John McCain walking off the plane from Vietnam, having a noticeable limp but certainly without any need of crutches. In Unz’s words,

It is certainly acknowledged that considerable numbers of American POWs were indeed tortured in Vietnam, but it is far from clear that McCain was ever one of them . . . [T]hroughout almost the entire war McCain was held at a special section for the best-behaving prisoners, which was where he allegedly produced his Communist propaganda broadcasts and perhaps became such good friends with his guards as they later claimed. Top-ranking former POWs held at the same prison, such as Colonels Ted Guy and Gordon “Swede” Larson, have gone on the record saying they are very skeptical regarding McCain’s claims of torture.

Unz points out that John McCain’s earliest claims of his harsh imprisonment, a highly detailed 12,000 word first person account published under his name in U.S. News & World Report in May 1973, just a few weeks after his release from imprisonment, contains many doubtful passages. Some were “perhaps drawn from the long history of popular imprisonment fiction stretching back to Dumas’s Count of Monte Cristo,” while in others McCain claimed he was spending his long period of solitary confinement “reviewing in his head all the many history books he had read, trying to make sense of human history, a degree of intellectualizing never apparent in his life either before or after”:

One factual detail, routinely emphasized by his supporters, is his repeated claim that except for signing a single written statement very early in his captivity and also answering some questions by a visiting French newsman, he had staunchly refused any hint of collaboration with his captors, despite torture, solitary confinement, endless threats and beatings, and offers of rewards . . . [Yet a] Counterpunch article provided the link to the purported text of one of McCain’s pro-Hanoi propaganda broadcasts as summarized in a 1969 UPI wire service story, and I have confirmed its authenticity by locating the resulting article that ran in Stars & Stripes at the same time. So if crucial portions of McCain’s account of his imprisonment are seemingly revealed to be self-serving fiction, how much of the rest can we believe? If his pro-Communist propaganda broadcasts were so notable that they even reached the news pages of one of America’s leading military publications, it seems quite plausible that they were as numerous, substantial, and frequent as his critics allege.

UNSTABLE PERSONALITY – McCain habitually screamed at his subordinates, red in the face and foaming at the mouth, calling them abusive names. He also shouted and insulted anyone opposing him, provided the person receiving abuse was visibly powerless (notably the POW/MIA family members, women included, at the Senate commission hearings). As Jeffrey St. Claire and Alexander Cockburn reminded us last week, a psychiatric evaluation of McCain by Spanish psychiatrist Fernando Barral presented the disturbing diagnosis of a deeply narcissistic personality, cold, aggressive, and largely devoid of human empathy.

McCain’s hysterical, sometimes literally uncontrollable outbursts reflected a profound personality disorder. His insecurity was probably enhanced by shame about his true war record. In his 1999 memoir McCain expressed guilt at having given the confession in Hanoi: “I felt faithless and couldn’t control my despair,” he wrote, and claimed that he made two “feeble” attempts at suicide. Tellingly, he says he lived in “dread” that his father would find out about the confession. “I still wince,” he writes, “when I recall wondering if my father had heard of my disgrace.”

It is still not completely clear whether the taped confession McCain gave to his captors—he admitted to being a war criminal who had bombed civilian targets—had played a role in his postwar behavior. It was played endlessly over the prison loudspeaker system at Hoa Lo and was broadcast over Hanoi’s state radio. Reportedly the Pentagon had a copy of the confession but would not release it. Also, no outsider has ever seen a non-redacted copy of the debriefing of McCain when he returned from captivity. It remains classified to this day; it could have been made public by McCain himself, but wasn’t. As veteran journalist Sydney Schanberg notes,

Many men undergoing torture give confessions, often telling huge lies so their fakery will be understood by their comrades and their country. Few will fault them. But it was McCain who apparently felt he had disgraced himself and his military family . . . In his bestselling 1999 autobiography, Faith of My Fathers, McCain says he felt bad throughout his captivity because he knew he was being treated more leniently than his fellow POWs, owing to his high-ranking father and thus his propaganda value. Other prisoners at Hoa Lo say his captors considered him a prize catch and called him the “Crown Prince,” something McCain acknowledges in the book.

McCain’s history of mental instability can best be understood in the context of his problematic relationship with his father, a top-ranking admiral who then served as commander of all U.S. forces in the Pacific Theater. As Ron Unz points out, in view of the disturbing headline of a 1969 UPI wire story—“PW Songbird Is Pilot Son of Admiral”—“it would have been imperative for John McCain’s father and namesake to hush up the terrible scandal of having had his son serve as a leading collaborator and Communist propagandist during the war and his exalted rank gave him the power to do so.” Interestingly, however, just a few years earlier the captive’s father had performed an extremely valuable service for America’s political elites: Admiral McCain organized the official board of inquiry that whitewashed the potentially devastating “Liberty Incident,” with its hundreds of dead and wounded American servicemen, “so he certainly had some powerful political chits he could call in”:

Placed in this context, John McCain’s tales of torture make perfect sense. If he had indeed spent almost the entire war eagerly broadcasting Communist propaganda in exchange for favored treatment, there would have been stories about this circulating in private, and fears that these tales might eventually reach the newspaper headlines, perhaps backed by the hard evidence of audio and video tapes. An effective strategy for preempting this danger would be to concoct lurid tales of personal suffering and then promote them in the media, quickly establishing McCain as the highest profile victim of torture among America’s returned POWs, an effort rendered credible by the fact that many American POWs had indeed suffered torture.

And so the legend grew over the decades, Unz concludes, until it completely swallowed the man, and he became America’s greatest patriot and war hero, with very few people even being aware of the Communist propaganda broadcasts. The best he claims for his reconstruction of McCain’s wartime history is that it seems more likely correct than not:

Just a few years ago an individual came very close to reaching the White House almost entirely on the strength of his war record, a war record that considerable evidence suggests was actually the sort that would normally get a military man hanged for treason at the close of hostilities. I have studied many historical eras and many countries and no parallel examples come to mind. Perhaps the cause of this bizarre situation merely lies in the remarkable incompetence and cowardice of our major media organs, their herd mentality and their insouciant unwillingness to notice evidence that is staring them in the face. But we should also at least consider the possibility of a darker explanation. If Tokyo Rose had nearly been elected president in the 1980’s, we would assume that the American political system had taken a very peculiar turn.

THE KEATING FIVE AFFAIR – Before leaving the military and entering politics, McCain served as the Navy’s liaison to the U.S. Senate, beginning in 1977. This was, in his own words, his first “real entry into the world of politics and the beginning of my second career as a public servant.” In April 1979 McCain made another key career move when he met and courted Cindy Lou Hensley from Phoenix, a very wealthy young woman. Her father approved of the marriage provided that John and Cindy sign a prenuptial agreement that would keep most of her family’s assets under her name. McCain’s children were appalled at his behavior and severed contact.

It was after the marriage to Cindy that McCain decided to leave the Navy. It is practically certain that he would never have been promoted to full admiral, as he had poor annual physicals and had never been entrusted with a major sea command. Living in Phoenix, he went to work for Hensley & Co., his new father-in-law large beer distributorship. As VP of PR at the firm, he gained political support among the local business community, meeting powerful figures such as banker Charles Keating Jr. In 1982, McCain ran as a Republican for an open seat in Arizona’s 1st congressional district. He won the primary thanks to the money that his wife had lent to his campaign. He then easily won the general election in the heavily Republican district.

McCain’s Senate career began in January 1987, when he succeeded longtime American conservative icon and Arizona fixture Barry Goldwater upon the latter’s retirement. He soon became embroiled in a scandal during the 1980s, as one of five United States senators comprising the so-called Keating Five Between 1982 and 1987, McCain had received $112,000 in political contributions from fraudster Charles Keating Jr. and his associates at Lincoln Savings and Loan Association, while simultaneously log-rolling for Keating on Capitol Hill. He took nine trips to the Bahamas on Keating’s jets. In 1987, McCain was one of the five senators whom Keating contacted in order to prevent the government’s seizure of Lincoln.

McCain was the kind of Republican that liberals love: military credentials, liberal on amnesty, rhetorically strong on campaign finance reform and similar bipartisan issues. According to Jeffrey St. Claire and Alexander Cockburn, in the run-up to McCain’s first presidential attempt in 2000, the New Yorker, the New York Times, Vanity Fair et al have all slobbered over McCain in empurpled prose, culminating in a love poem from Mike Wallace in 60 Minutes, who managed in one whole hour to avoid any mention of McCain’s relationship with Keating: “McCain’s escape from the Keating debacle was nothing short of miraculous, probably the activity for which he most deserves a medal . . . When the muck began to rise, McCain threw Keating over the side, hastily reimbursed him for the trips and suddenly developed a profound interest in campaign finance reform.”

McCain was arguably the most blameworthy of the Keating Five, but he used his POW status and the complicit media to not only get out of harms way, but to save his political career in the process. In the end he was cleared by the Senate Ethics Committee of acting improperly but was rebuked for exercising “poor judgment.” In later years McCain became a poacher-turned-gamekeeper, railed against the corrupting influence of large political contributions, even made this his signature issue. But in 1997, when he became chairman of the powerful Senate Commerce Committee, he continued to accept funds from corporations and businesses under the committee’s purview. A Senate staffer offered these observations on McCain’s fundamental weakness of character:

The real question is why this Senator did not use the strong leverage he has to insist that his ‘ethical’ position be incorporated into a major bill? . . . [But] this place doesn’t really operate that way. Here, they have contempt for fluffy show pieces. Show them you mean business, and you’re someone who has to be dealt with (rather than a talk-only type), and you’ll begin to get some results. Get ready for a fight, though, because they are some on the other side who are no push-overs. Obviously, Mr. McCain was not prepared to make that investment.”

Regardless of what they told the media last week, many colleagues in the Senate knew that McCain was a mere grandstander, always happy to receive tons of pac money from the companies that craved his indulgence as chairman of very influential committees (first commerce, then armed forces). They also knew that he had a very wealthy wife that his supposed support for ending soft money spending would never get any tangible legislative application.

McCain announced his first candidacy for president on September 27, 1999, saying he was staging “a fight to take our government back from the power brokers and special interests, and return it to the people and the noble cause of freedom it was created to serve.” That was rich, coming from a power broker par excellence and a dedicated servant of special interests. On the whole, then or in later years, there was nothing “conservative” in McCain’s infatuation with big government, which he helped quadruple in size and scope during his lifetime, or in his enthusiasm for the PATRIOT Act and Military Commissions Act. From birth until death he was a pampered child of the military-industrial-security state as well as its zealous guardian, an enemy of liberty and constitutional tradition.

POW/MIA ISSUE – Former New York Times reporter Sydney Schanberg, a Pulitzer Prize laureate, has written a long and meticulously documented account of McCain’s role in suppressing information about the fate of American soldiers missing in action in Vietnam. According to Schanberg, McCain—who owed his political career largely to his image as a Vietnam POW war hero—had “inexplicably worked very hard to hide from the public stunning information about American prisoners in Vietnam who, unlike him, didn’t return home.” For much of his Senate career, he had sponsored and pushed into federal law a set of prohibitions that keep the most revealing information about these men buried as classified documents.

Thus the war hero who people would logically imagine as a determined crusader for the interests of POWs and their families became instead the strange champion of hiding the evidence and closing the books. Almost as striking is the manner in which the mainstream press has shied from reporting the POW story and McCain’s role in it, even as the Republican Party had made McCain’s military service the focus of his presidential campaign. Reporters who had covered the Vietnam War turned their heads and walked in other directions… There exists a telling mass of official documents, radio intercepts, witness depositions, satellite photos of rescue symbols that pilots were trained to use, electronic messages from the ground containing the individual code numbers given to airmen, a rescue mission by a special forces unit that was aborted twice by Washington—and even sworn testimony by two Defense secretaries that “men were left behind.” This imposing body of evidence suggests that a large number . . . of the U.S. prisoners held by Vietnam were not returned when the peace treaty was signed in January 1973 and Hanoi released 591 men, among them Navy combat pilot John S. McCain.

McCain was also instrumental in amending the Missing Service Personnel Act, which had been strengthened in 1995 by POW advocates to include criminal penalties (“Any government official who knowingly and willfully withholds from the file of a missing person any information relating to the disappearance or whereabouts and status of a missing person shall be fined . . . or imprisoned not more than one year or both”). A year later, in a closed House-Senate conference on an unrelated military bill—and at the behest of the Pentagon—McCain attached a crippling amendment to the act, removing the criminal penalties and reducing the obligations of field commanders to search for missing men and to report the incidents.

As Schanberg points out, McCain had insisted again and again that all the evidence—documents, witnesses, satellite photos, two Pentagon chiefs’ sworn testimony, aborted rescue missions, ransom offers apparently scorned—had been woven together by unscrupulous deceivers to create an insidious and unpatriotic myth. He called it the “bizarre rantings of the MIA hobbyists”. . . “hoaxers,” “charlatans,” “conspiracy theorists,” and “dime-store Rambos”:

Some of McCain’s fellow captives at Hoa Lo prison in Hanoi didn’t share his views about prisoners left behind . . . Col. Ted Guy, a highly admired POW and one of the most dogged resisters in the camps, wrote an angry open letter to the Senator . . . : “John, does this [the insults] include Senator Bob Smith [a New Hampshire Republican and activist on POW issues] and other concerned elected officials? Does this include the families of the missing where there is overwhelming evidence that their loved ones were ‘last known alive’? Does this include some of your fellow POWs?”

At the Senate POW committee hearings, McCain browbeat expert witnesses who came with information contrary to his assertions and screamed at family members who had personally faced him, insulted them, brought women to tears. (Let us note in passim what Henry Kissinger wrote his memoirs, solely in reference to prisoners in Laos: “We knew of at least 80 instances in which an American serviceman had been captured alive and subsequently disappeared. The evidence consisted either of voice communications from the ground in advance of capture or photographs and names published by the Communists. Yet none of these men was on the list of POWs handed over after the Agreement.”) Ron Unz’s conclusion is damning, and disheartening:

In 1993 the front page of the New York Times broke the story that a Politburo transcript found in the Kremlin archives fully confirmed the existence of the additional POWs, and when interviewed on the PBS Newshour former National Security Advisors Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski admitted that the document was very likely correct and that hundreds of America’s Vietnam POWs had indeed been left behind. In my opinion, the reality of Schanberg’s POW story is now about as solidly established as anything can be that has not yet received an official blessing from the American mainstream media. And the total dishonesty of that media regarding both the POW story and McCain’s leading role in the later cover up soon made me very suspicious of all those other claims regarding John McCain’s supposedly heroic war record. Our American Pravda is simply not to be trusted on any “touchy” topics.

WARMONGER – In global affairs, McCain’s “vision” amounted to assailing designated adversaries—meaning anyone unenthusiastic about America’s monopolar global empire—and demanding they be forced into submission by American “boots on the ground” (his favorite phrase). At the same time, he was eager to use genuine monsters—notably, assorted Islamic State and Al Qaeda jihadists—as tools of U.S. hegemony. After meeting their leaders in Syria in 2013, he called them “brave fighters who need our help.” He poured scorn on powerful countries such as Russia (“a gas station masquerading as a country”), or China (“ruthless, inhumane regime”), and on weak ones such as Serbia, where during Bill Clinton’s 1999 war of aggression he advocated bombing civilian targets.

In March 1999, McCain voted to approve the NATO bombing campaign against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, saying that “the ongoing genocide of the Kosovo War must be stopped” and criticizing past Clinton administration inaction. The “genocide” was a lie, but the bombs hitting purely civilian targets were real. As Jeffrey St. Claire and Alexander Cockburn reminded us last week, in one rhetorical bombing run after another McCain had bellowed for “lights out in Belgrade” and for NATO to “cream” the Serbs. At the start of May 1999, he began declaiming in the US senate for the NATO forces to use “any means necessary” to “destroy Serbia.”

Three years later, in discussions over proposed U.S. action against Iraq, McCain stated that Iraq was “a clear and present danger to the United States of America” and voted accordingly for the Iraq War Resolution in October 2002. He predicted that U.S. forces would be treated as liberators by the Iraqis. By November 2003, after a trip to Iraq, he said that victory was possible but more U.S. troops were needed. In his fifth Senate term, during the “Arab Spring” of 2011, McCain called on the embattled Egyptian president, Hosni Mubarak, to step down and urged the U.S. to push for “democratic reforms” in the region—paving the way for the brief and disastrous period of Muslim Brotherhood rule. (He also gained attention for defending State Department aide and Hillary Clinton protégé Huma Abedin against well-documented charges brought by several House Republicans and others that she had close links to the Muslim Brotherhood.)

McCain was a vocal supporter of the 2011 military intervention in Libya. In April of that year he visited the jihadist anti-Gaddafi forces in Benghazi, the highest-ranking American to do so, and said that the rebel forces were “my heroes.” (The following year these same “heroes” murdered Ambassador Stevens in Benghazi.) In June 2011, he joined with Senator Kerry in tabling a resolution that would have authorized U.S. military intervention. Starting in 2013 and until the end McCain supported the Saudi military intervention in Yemen against the Shia Houthis. To a question about massive civilian casualties resulting from Saudi air strikes he replied, “I’m sure civilians die in that war—but not nearly as many as the Houthis have executed.”

John McCain never saw a war he did not like, or an issue for which war was not the solution. He voted for the one in Iraq and relentlessly demanded another against Iran. He supported intervention in Libya and demanded an enormously enhanced one in Syria. In a display of crass frivolity, a decade ago he hummed a riff on the Beach Boys’ “Barbara Ann,” “bomb, bomb, bomb, bomb bomb Iran.” In a sane country such behavior would be deemed scandalous. Not in Washington, where it is possible for a secretary of state to declare that starving half a million Iraqi children to death was the price worth paying in pursuit of a higher policy objective. Further north, in every post-Soviet frozen conflict he supported greater U.S. “engagement” in confronting Moscow. His Russophobia was truly obsessive. In 1999, he accused the Clinton administration of ignoring Russian “crimes” in Chechnya. In early 2008 he boasted of staring into Putin’s eyes and seeing the letters “KGB.” Very early on and without proof he denounced Russia for “interfering” in the 2016 presidential election.

McCain reveled in the spectacle or prospect of raw violence, in the service of what his former advisor, neocon guru Robert Kagan, termed America’s “Benevolent Global Hegemony.” McCain hated Donald Trump for many reasons personal and ideological—he was a good hater—but primarily for declaring he wanted to retreat from the lust for full spectrum dominance. McCain went to the Munich Security Conference in February 2017 to deliver—to a foreign audience—a vile ad hominem attack on the President. In 2015 he achieved his longtime goal of becoming chairman of the Armed Services Committee. He helped boost military spending to an astronomic level, $717 billion per year, but lacked a strategic vision to give such extravagance rational meaning. (True to form, the media only found it scandalous that Trump did not name the spending bill after McCain.)

AMNESTY – Working for many years with Democratic Senator Ted Kennedy, McCain was a leading proponent in the Senate of thorough immigration reform based on mass amnesty of illegals, and mendaciously called The Secure America and Orderly Immigration Act. For this very reason, two decades ago John McCain attracted the attention of, and found a benefactor in, George Soros. The philanthropist-from-hell supports the Democratic Party, but as an astute speculator Soros was loath to limit his options. Both in 2000 and in 2008, in candidate McCain, he had a nominal Republican who was willing to pursue key points of his open-borders agenda. In the early 2000’s McCain’s Reform Institute promoted a key pillar of Soros’s agenda—open and unlimited Third World immigration—and was paid for doing so. To be fair, McCain’s position on immigration did not depend only on the cash: He was an honest amnesty enthusiast.

In June 2007, President Bush, McCain, and others made a concerted push for the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007—essentially the same bill—but it aroused intense grassroots opposition among the GOP base and twice failed to gain cloture in the Senate. McCain had formally announced his intention to run for President two months earlier, and his support of the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act threatened his candidacy. His decision to choose Sarah Palin as his running mate was a cynical attempt to appease the conservatives in general and the Tea Party movement in particular. It backfired spectacularly. Palin was palpably out of her depth; voter reactions to her grew negative, even among GOP voters who were rightly concerned about her qualifications. McCain’s was the worst GOP presidential campaign in living memory, with the possible exception of Bob Dole’s disastrous performance in 1996.

TRUMPOPHOBE – During the 2016 Republican primaries, McCain announced he had serious concerns about Trump’s “unin

Leave a Reply