Out of thin air—or of mythic consciousness—a Texas governor once plucked unhesitatingly the mot juste. The governor, Allan Shivers, who served back in the 1950’s, was indignant over some piece or other of legislative tomfoolery. As he saw it, the whole enterprise was downright “un-Texan.”

“Un-Texan.” Right there we had the nub of the matter. No deeper truth, no higher reality, needed to be fingered. The governor’s listeners were to understand that two standards informed political discourse and deliberation—one for Texans and another for everybody else. The Greeks, whose word for foreigner was “barbarian,” would doubtless have understood.

Texas is different, yes, when measured against the standards of Michigan, North Carolina, and South Dakota. Has any measure of uplift or social transformation ever been condemned as un-Carolinian? Un-Dakotan? In the federal union of states, Texas is distinct all right. It may be even more distinct than the legends suggest and all the more meritorious for that—at least from a certain philosophical vantage point.

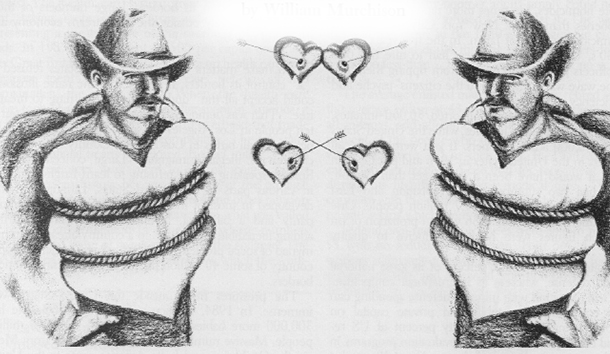

I give fair warning: we are traversing here the countryside of myth. Step carefully. The Texas myth of real men in the wide open spaces is notoriously potent, engaging—and dangerous. Dangerous because it leads to exaggeration: the blam-blam, take-that-you-varmint kind. I never cease to be amazed—yes, even in this year of grace 1989—at how many non-Texans believe our state to be populated chiefly by cattlemen and oil barons. An informal survey I have conducted reveals that we have slightly more of these types than England has monocled earls who say “pip, pip.”

Mere statistical veracity is nevertheless not the point. The point is that nobody, however large his moneybags, leads Texans around by the nose or tells them what to think or how to think it. The standards, the norms, of Texas grow from the grassroots. Those roots may, and often do, yield wealth and power, but wealth and power are not permitted to overgrow the plot as a whole.

This is with the usual exceptions, carved out to accommodate human nature. Texans, like Kentuckians, Utahans, and Rhode Islanders, admire wealth; they enjoy driving big cars, shopping at Neiman-Marcus, and being photographed at fancy parties. But with admiration goes a certain skepticism about the importance of money in the great scheme of things.

The opinions of the rich do not receive automatic deference. Most Texas money, in an ever-changing economic climate, is new, or at best newish—40 or 50 years old. Joe Ed can recollect back when Jim Bob was dirt poor, and just because Jim has that fancy computer company now . . . well, you know what they say about here today, gone tomorrow. (Skepticism about wealth comes all the easier in the late 80’s, what with the collapse of a speculative real estate market that propelled to power some very sharp and very flashy operators.)

Money and wealth are not the only measuring sticks, of course. There is also intellect. Intellectuals notoriously like telling other people what to think. In Texas they rarely get away with it. Here there is no aristocracy of brains any more than there is an aristocracy of cash.

This may sound more condescending than it is meant to sound. Texans are as bright and witty as people elsewhere. It merely happens they resist sitting openmouthed while others lay down the law. The law? They can figure that out for themselves. Texans need no intrusive interpreters.

The Baptists, whose creed is the noncreed of “every man his own priest,” have ever flourished in Texas. According to the 1980 census, Southern Baptists were three times more numerous than the Methodists; they outnumbered the Episcopalians, with their prayer books and bishops, 16 to 1. The gaps have no doubt widened since then.

No university of truly national stature can be found in Texas or has ever been found there. The main campus of the University of Texas, located in Austin, boasts particular departments that are first-rate; Rice University has a long tradition of excellence, particularly in science and mathematics; and Texas A&M University is ambitiously contending the yokel image of yore. But there are no Harvards in these here parts, or Stanfords; not even any Cal-Berkeleys or Michigan and Indiana U’s. There are no such-universities because Texans have not demanded there be.

The lack of demand frustrates Texas business leaders, who preach that a technological future requires a welltrained work force. (Note the appeal to practical, as opposed to abstractly intellectual, interests.) So far these leaders have failed to make a big impression on the public consciousness.

I do not see Texas grieving wholesale over the deficiency of world-famous centers of learning. Nor can it be all to the bad, casting a suspicious eye on intellectuals and the paraphernalia of intellectualdom. Texas has no great universities, but neither has it much susceptibility to professorial theories of angst and alienation and the duty of an intellectual caste to shepherd the lowing herd.

What do you do with people so hardheaded, so rancorous, so unwilling to be led around and preached at as Texans are? One possibility is to stare with a certain admiration, not to mention disbelief. The 21st century draws near, yet the Lone Star State clings to attitudes more generally identified with the 19th century, a time of callouses and broad vistas of opportunity. Plus ça change: Government, religion, learning, life in general; whatever it is, authority in Texas still rises from the bottom. Texas is as thoroughly democratic a venue as you will find in America. But that does not say it all. Democracy-from-the-ground-up proves to have consequences different from those where democracy is imposed or stimulated by the top. The people truly speak in Texas. They speak a language only dimly apprehended, at best, in places like Brookline, Massachusetts.

What do we call this language, this philosophy? Populism? Maybe so, but to do so is to run some risks. No word in the political vocabulary is more abused than “populism,” unless the word is “democracy.” Richard Nixon was wrong: we are not all Keynesians; in the 1980’s we are all populists. Every last one of us these days is heartily for “the people.” What divides us is the divergent ways in which we are for the people.

In Texas, Phil Gramm, the energetic free-marketeer who is the state’s junior US senator, campaigns as a populist—one who wants to free the people from the suffocating embrace of government. A populist of a different stripe is State Treasurer Ann Richards, who won guffaws at the Democratic National Convention by ridiculing “the silver foot” in George Bush’s mouth.

Richards tossed out Texanisms galore (Southernisms, really) as she swung her rolling pin at Bush. The nation learned about old dogs that won’t hunt and cows that eat the cabbage, and was assured this is the way good liberal populists talk to each other. It happens that I learned all these phrases, and learned to relish them, from parents who last voted for a Democratic presidential candidate in 1936. Slinging around the patois of the people isn’t the same as appreciating the views of the people, many of those views bred in the bone, inarticulately understood, and stoutly maintained against all comers.

Gramm and Richards represent, and to some degree speak authoritatively for, the two principal strains of Texas populism. Gramm’s variety is the more common, the more deeply grounded in Texas history. Old-style Texas populism, as represented by Governor Jim Hogg back in the 1890’s, had a small, a very small, quotient of socialistic envy and desire to punish the striped-pants set. There were radical farmers in Texas, as there were radical farmers all over the South and Midwest. Texans, nevertheless, did not cry out with one accord for the big companies to be knocked down and flayed alive for the crime of business.

Texans did not dislike “business” as such. What they disliked was big, foreign-owned (meaning New York-owned) business; business uncontrolled, uninhibited, and grasping. The Texan was by no means antibusiness; fact was, he’d always had a hankering to set up for himself, be his own man. What was the point of living in Texas, it could fairly be asked, if you failed to relish the economic opportunities Texas afforded? Why not move to Connecticut or Virginia?

Jim Hogg might inveigh against monopolistic railroads, but when the mammoth Spindletop oil field was discovered near Beaumont in 1901, he was among the first Texas entrepreneurs to jump in and develop the field. The company Hogg helped to organize is known today as Texaco.

The Texas Railroad Commission, a regulatory agency Hogg helped establish after a noisy political campaign, carefully refrained from railroad-bashing and other endeavors to diminish commerce and jobs. The commission later was given legal oversight of the oil industry Hogg had helped to found.

In due course the Railroad Commission became the oil industry’s bosom friend and tireless promoter. Commissioners regularly journeyed to Washington to plead for tax breaks and higher prices. Whenever oversupply threatened to drive down prices, the commission lowered the monthly allowable—the amount of oil individual producers were allowed legally to produce. Until the rise of OPEG, market-demand proration in Texas kept prices firm and the industry, meaning not only bosses but workers by the hundreds of thousands, generally prosperous.

The Railroad Commission, both during the glory days of oil and the subsequent energy squeeze, entertained no notion of an eternal vendetta between consumers on the one hand and companies on the other. The assumption was that both groups were interested in reliable supplies at affordable prices.

Liberal populism is of another cast and variety. Its exemplar is not really Ann Richards but Jim Hightower, the tart-tongued commissioner of agriculture who is said to thirst for Phil Gramm’s Senate seat. Liberal populism basically distrusts business and businessmen. It would endorse Joe Kennedy’s dictum, gleefully retailed from the White House by his son John, to the effect that businessmen are SOB’s.

The liberal populist makes a great show of loving the people. Jim Hightower wears a cowboy hat and refers to himself, in feverish moments, as “Whole Hog” Hightower. The philosophy these populists spout is hardly discernible from the collectivism preached at the loftiest level of the intellectual establishment. Business is to be tolerated, yes, but given its head? Never! Liberal populism holds that government must guide and harmonize the helter-skelter processes of the marketplace. Jim Hightower and Michael Dukakis have more in common, at the end of the day, than do Jim Hightower and Phil Gramm.

No wonder that liberal populism has never triumphed, or even scored more than marginal and temporary victories in Texas. The last liberal governor of Texas left office in 1939. He was one Jimmy Allred, and even he had his conservative side. Liberal populism is too snooty, too managerial, to win easily popular favor. It condescends to the very people it professes to love. Conservative populism understands and appreciates the orneriness of the human species; it knows that branding irons and hobbles are for horses, not citizens.

Change could be in the offing, as indeed change of some sort is always in the offing. Major Texas companies, in these austere times, are being bought out by the gross. The new owners are laying off Texans and laying on deracinated managerial types with business school degrees. I see with my own eyes resentment growing against the bottom-line mentality. But this does not yet translate into dislike of capital, only of particular capitalists. Unless businessmen as a class grow stupider than the rigors of competition generally allow them to grow, Texan hospitality to business should survive and transcend the present hard times.

It’s indicative that in the 1988 election, George Bush, the pro-business candidate, carried Texas by 12 percentage points. In the centers of commerce—cities like Dallas and Houston—Bush obliterated Dukakis. The state’s large and mostly flourishing middle class strongly, and not unreasonably, distrusted Dukakis’s economic nostrums.

Meanwhile Texans hold tenaciously to the old belief that welfare undermines the human spirit, besides draining the state’s financial resources. Texas is the stingiest—or the most sensible, depending on your viewpoint—of the 50 states in providing aid to families with dependent children. Immigrants come to Texas to work, not to go on welfare.

No values look more durable than those social and moral standards fertilized in the soil of populism. Texas, though hardly untouched by the ravages of the 20th century, may be the out-prayingest state in the union. Church attendance does not tell the whole tale. In history’s most secularized era, Texas business luncheons commonly begin with the invocation of God’s blessing upon our food and our purpose in coming together. As do PTA meetings, though not classes, at the public elementary school in my neighborhood.

Liberal Christianity, in Texas, sends up only the spindliest shoots—Baylor University in Waco, regarded by most non-Southern Baptists as a bastion of biblical righteousness, increasingly draws the fire of Baptists who consider its faculty too liberal. It is a matter of perspective. In Texas, “liberal” does not mean what it means in Massachusetts.

Patriotism is yet another value that deeply informs the Texas outlook, as you might expect of a people baptized in war and revolution. Protests against the Vietnam War were almost nonexistent in Texas. All the action in the 60’s seemed very distant. There were no homegrown protesters of any numbers or influence, which was probably just as well. Whatever Texans missed in the way of adrenergic excitement, they gained in the way of social peace.

Texans always have been in the forefront whenever the nation called for volunteers. Theodore Roosevelt recruited the Rough Riders in San Antonio. The 36th Division, made up mainly of Texas National Guardsmen, was heroically bloodied in the Italian theater during World War II. And so on through the annals of military history. Texans fought against the United States flag from 1861-65, but made their peace in due course and today accept no backseats in the matter of national loyalty.

It’s true that Texas, in 1989, is not what it used to be; but then it never has been what it used to be. A century ago, the closing of the frontier and the cessation of the Indian wars brought forth a new Texas . . . as has, in recent years, large-scale immigration by Northerners, Hispanics, and Asians; as have the decline of the family farm, the implosion of the oil and real estate booms, the rise of the Republican Party.

Cities and freeways have burgeoned. There are Texas children who go years without seeing a cow, except of course on Sesame Street.

Outward and visible realities pass away, yes; but inward and invisible realities exercise a tenacious hold on the people who, wherever they were born, call themselves Texans. The fierce individualism, the belief in hard work and the possibility of personal achievement, the sense of dependence on the favor of an unseen Deity—these things endure. This is not the only way obviously, but this is the Texas way—now, and, please God, a century from now.

Leave a Reply