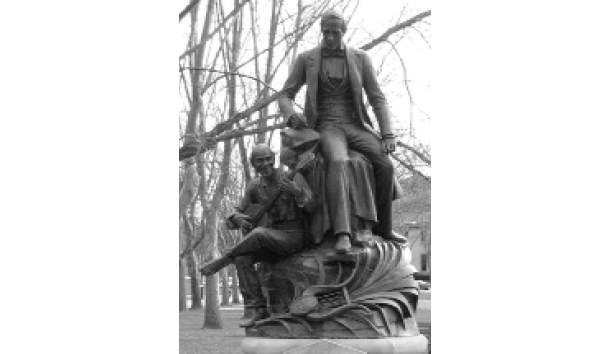

History is rewritten, memory is transformed, recognition is withdrawn, and the cultural context is recast. The recent toppling of historical statues has proceeded so effectively that we can hardly remember a previous period of statue erection or insertion in Richmond, Virginia. The former capital of the Confederacy had to be punished for its Monument Avenue, so in 1996 the tennis champion Arthur Ashe was put in a sequence with Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and J.E.B. Stuart. Did the ambiguous word volley have an equalizing effect on the rationalized incongruity? Another statue—of Abraham Lincoln and his son, Tad—was surreptitiously placed on Tredegar Street in 2003. Those were the days—and nights—when statues went up rather than down.

There have been many removals of statues, and complaints extending even to “Defacing Columbus.” There were the removals of statues in Texas of Albert Sidney Johnston (“the General of Three Republics”) and of Dick Dowling of the celebrated Battle of Sabine Pass, making it all the more puzzling why Texans today would be so indifferent to such Texans then.

I do admit that this is an oblique approach to matters of musical interest, but I think that as with “The Star-Spangled Banner” and Francis Scott Key, historical revisionism does leap from category to category. And music is a monument of a kind, if it survives in memory. We would not wish to dismiss arbitrarily any particular musical achievement that is a vision of the past, or an entry into it. A magazine of American culture would be forced to declare, I daresay, that so much of the inherited stuff of that culture was made of such questionable material, that the cultural patrimony as such may be doomed as vital culture. To take an obvious but productive example, we can consider the case of Stephen Collins Foster (July 4, 1826-1864).

Not so long ago, Foster was still as well known as he ever had been. The tradition of singing in America made his songs live for rising generations, and this since the Civil War. The dynamic that had pushed the Foster lyrics and Foster music as creations and as commercial products had been synthesized before the War by such groups as the Christy Minstrels and other blackface minstrels as well as popular forms of comedy, sentiment, and entertainment. The phonograph later opened up new possibilities for the treatment of the Foster songs as living popular music, and also as the American lyric that has been compared with the songs of Schubert. And though there were many individual recordings of various songs, those by Richard Crooks, Robert White, and Thomas Hampson seem to be the best. If I had to pick some performances of the many fine ones, I would point to Hampson’s “Comrades, Fill No Glass For Me” and “Hard Times, Come Again No More” as superb renditions. They must be heard to be appreciated—and they remind us that abolition and temperance were, with female suffrage, the three great social movements of the antebellum era. Foster’s songs spoke to two of those, and more than once.

Though many today would probably see his worldview as racist, abolitionist feeling is there in Foster’s work. There are, no doubt, many cringe-inducing songs. Certainly, it is true that Foster exploited all opportunities for the use of sentiments and issues, but his sense of the wrong of slavery is there, even as he flaunts stereotypes. The leading black abolitionist, Frederick Douglass himself, insisted on the nuances of a Foster song, even during those days of bitter struggle. In Douglass’s 1855 autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, he asserts that the 1853 song “My Old Kentucky Home” “awakens sympathies for the slave, in which antislavery principles take root, grow, and flourish.” And if we look closely at the lyrics, we can see that Douglass’s thought is confirmed. To write the song off as “racist” is rather to miss the point.

In other cases, writing the song off as racist, as demeaning, or as justifying a fantasy of happy slaves, is the point. This would be true of “Massa’s in the Cold, Cold Ground,” for instance: “Massa made de darkeys love him / Cayse he was so kind.” There is no question that some or much of this material is irredeemable—but it was written to please, it was performed successfully by the Christy Minstrels, and it is part of history.

Today, “My Old Kentucky Home” shares a distinction with “Swanee River,” that of being the official song of a state, the one of Kentucky, and the other of Florida. Both of these songs have been “expurgated” or “bowdlerized” or discreetly rewritten in order for them to remain the songs of states, and I think that is justifiable, simply because to insist on the original lyrics would necessarily have meant the songs’ elimination by the states that claimed them.

But I also think that something bigger than geography or even history is operative in the states’ adoptions of these songs. Both “My Old Kentucky Home” and “Swanee River” are powerful evocations of the fear of loss, of homelessness, of the dissolution of families, of missing the old folks at home. Though these themes are filtered through the lens of slavery, they are, nonetheless, universal human concerns. And I also notice an acknowledgement of the power of art, even in its popular presentation. The states wanted to harness the charisma of the music and the lyrics—not the other way around. Maybe it was the other way around, when Foster wrote the songs, but not after a century and more.

There is something confusing about Foster, for he gives the impression that he is a celebrator of the South and an exploiter of slavery. But we know better than that. Foster was a Northerner by birth and inclination. He stayed true to the North and supported the War and Lincoln—he wrote “We Are Coming, Father Abraham, 300,000 More.” We also know that Daniel Emmett, who wrote “Dixie,” was a Northerner as well—and that Lincoln liked “Dix ie” as a tune. So this confusion is not so much about Foster as it is about the music and entertainment of the day. Foster and Emmett were exploiting the situation as they found it. Such was the nation before the War, the end of which Foster did not live to see. If he had lived longer, he probably would have taken musical and sentimental advantage of the new situation.

My intuition—the one that keeps telling me that I am going to win the lotto—tells me that “Beautiful Dreamer” is a great song and probably among Foster’s best. Now when we approach such a song, we don’t have to be alert to racial issues, but we do today have to be particularly sensitive to considerations of sex. And there are some problems there, perhaps reminiscent of similar effects in works of Edgar Allan Poe. In a repeated situation, we are supposed to concentrate on a female who is dead, or seems to be, or might as well be.

In “Thou Shalt Come No More, Gentle Annie,” the female subject is the occasion for a lament in which Gentle Annie seems to be identified with natural processes. Flowers die, but not only those. We might note here that the association of the female principle with the generation of life and its enhancement is not affirmed. Rather, the death of the maiden seems to be something of a welcome topic for verse and music. To put it another way, the notion of approaching the female subject only when that subject is asleep does not seem to be an approach that speaks to the emancipation of women, the education of women, female suffrage, or indeed much of anything else, including marriage, childrearing, familial concerns, and household management.

“Come Where My Love Lies Dreaming” does not have much substance beyond its title. “Dreaming the happy hours away” pretty much exhausts the store of words and images. The associated “Beautiful Dreamer” is more rich and extended, and it reminds us that sometimes the man really was a poet. But the word vapor in both “Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair” and “Beautiful Dreamer” is less auspicious than it is suspicious—it suggests the evanescence of a fragile myth. Must romantic love rest on such an insubstantial wisp, after all? Is a dream that real, or worth so much? And even if it were, how could we be sure that we know what images delude the dreamer?

My final word about Stephen Collins Foster circles back to our beginning and to the song “My Old Kentucky Home.” In that song, sentiment is fortified with truth, and feeling is strengthened with an insistence on physical reality that must be remarked. It all shows up in the engineering of seemingly related words in the third verse.

The head must bow and the back will have to bend,

Wherever the darkey may go;

A few more days and the trouble all will end,

In the field where the sugar-canes grow.

A few more days for to tote the weary load,

No matter ’twill never be light;

A few more days till we totter on the road,

Then my old Kentucky Home, good-night!

Now how about that for indulgent sentiment! I am struck not only by the alliteration in the first line, and by the presentation of being “sold down the river” as a sentence of death, but even more by the creative collision of “tote” and “totter.” The enforced labor is fatal overwork. The similarity of tote and totter is interesting, striking to eye and ear, and perhaps even more, as totter is possibly Scandinavian in derivation, and it has been suggested (though not definitively) that tote is West African! In any case, “Tote the Weary Load” was the working title for Gone With the Wind, and before we say goodbye to it, we would have to acknowledge the effective hypallage, or transferred epithet. The load itself is not weary. The exhausted human being who must bear it—even to the point of death—is the weary one.

Leave a Reply