We had been dreaming about Andalusia. But plans sometimes must be altered, and so one August evening we found ourselves instead entering into Ulverston, 1,300 miles from Andalusia, and even more distant climatically, culturally, and historically. The Lake District—“England’s Switzerland,” Manchester’s playground, stamping grounds of Wordsworth and Beatrix Potter—is a magnet to millions of tourists, subject of a billion photos, noted for traffic jams, tea shops, lake cruises, mint cake, and hikers in fluorescent cagoules. These images were unappealing, especially when juxtaposed with thoughts of Spain. Our prior experiences had been gray days around Ambleside, trooping in everyone else’s damp wake, reading the same rain-spotted information boards, and taking the same photos. I had also come here on a coaster, coming alongside at Silloth on Christmas morning, and had vague remembrances of cold, empty streets, flour mills, and the smell of fertilizer. The effect of such impressions had hitherto been to make us defer exploration when there were so many other places, and so little time. But as I plundered my bookshelves, the District soon loomed into shape—and by the time we were climbing to our cottage through lanes of bruised bracken, the great glitter of Morecambe Bay below and sheep-smelling hills rising up all round, any lingering regrets were vanquished.

The 90-square-mile District was divided historically between Lancashire, Cumberland, and Westmorland, but in 1974 it was all subsumed into the new county of Cumbria (to considerable chagrin). There are 64 lakes, including Windermere, England’s biggest at over ten miles long and nearly a mile wide, and Wast Water, its deepest at 258 feet—a product of high rainfall, plus the impermeability of volcanic rocks. Some water bodies still hold Ice Age relicts like Arctic char and vendace, fish rare elsewhere and threatened even here by non-natives. There are 180 mountains of over 2,000 feet, including Scafell Pike, England’s highest at 3,209 feet. This strongly marked landscape is sparsely populated outside the summer season, with its largest town, Kendal, having fewer than 30,000 permanent residents. Small wonder the area has attracted superlatives since the English started to take an aesthetic rather than a utilitarian interest in landscapes, at that 18th-century cultural cusp when Augustan tastes were toppled, wilderness turned into scenery, and emotion and self-realization began to be exalted over reason and restraint.

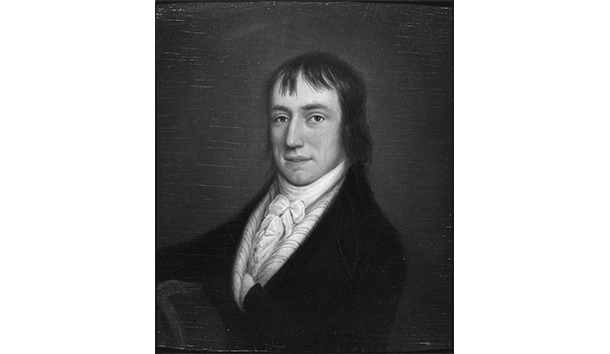

In 1769, Thomas Gray could still find these mountains “very rude and awful with their broken tops,” but the following year William Wordsworth was born in Cockermouth, a lawyer’s son who would become the area’s greatest interpreter and publicist, and England’s Romantic-in-Chief. His Prelude recalls a childhood spent chiefly outside, by the Derwent which “flowed along my dreams,” or out on screes and slopes, catching woodcock, robbing ravens, or just rhapsodizing—epic walks, summer swims, ice-skating, cliff-climbing, wild winds, “distant Skiddaw’s lofty height . . . bronz’d with a deep radiance.” Presently, he started composing poetry to “find fit utterance for the primary and simple feelings” (Dictionary of National Biography), developed democratic sympathies, met Coleridge and Southey, and settled with his sister at Dove Cottage overlooking Grasmere.

His penchant for recreational walking was much mocked—“His legs were pointedly condemned,” joked English Opium-Eater Thomas De Quincey, who moved into Dove Cottage after the Wordsworths, and improbably became editor of the Westmorland Gazette. Wordsworth’s character was also assailed, particularly when his poetry strayed into bathos (notoriously, “SPADE! with which Wilkinson hath tilled his lands”) and his politics turned Tory. His outlook was ridiculed by, among many others, William Hazlitt, who scoffed that Wordsworth “sees nothing but himself and the universe.” Some moderns are even less forgiving, like Rebecca Solnit in Wanderlust: A History of Walking (2000)—“He went from being a great Romantic to a great Victorian, and the transition required much renouncement.” Solnit even regrets he did not die in his late 30’s, which might admittedly have been inconvenient for him and his family, but would luckily have left “his image as a radical intact.” Notwithstanding such charitable considerations, Wordsworth’s Weltanschauung—an amalgam of love of nature, fascination with the past, slightly philistine patriotism, and unbounded sentimentality—still permeates the Lake ambience and England’s view of herself.

Behind all romancing, and even when the weather is fine, the District feels unyielding. Even Beatrix Potter’s treacly tales have a granite-gleam of toughness, her Peter Rabbits, Jeremy Fishers, and Jemima Puddle-ducks anatomically correct under all the anthropomorphism, product of a lifetime observing and depicting fauna and flora. (She had a special interest in fungi, and in 1897 presented a paper to the Linnaean Society of London on “Germination of the spores of the Agaricineae.”) An even solider achievement was that she was able to bequeath 4,000 acres of the area to the nation upon her death in 1943, courtesy of Mr. Tod, Tommy Brock, and the Tailor of Gloucester. Less comforting animals were Richard Adams’s Plague Dogs, the labrador Rowf and the Jack Russell Snitter of his searing 1977 antivivisection novel, experimental subjects who escape from an animal research center to live wild for a while aided by another tod, the starving stoniness setting for the moral desolation of the experimenters.

This was for centuries a frontier zone whose clouded hills could at any moment unleash moss-troopers and reivers. It got coopted into wider wars, one Civil War legend telling how Sir Robert Philipson (a.k.a. “Robin the Devil”) of Belle Isle on Windermere rode right into Kendal’s parish church in angry, unsuccessful search of one Colonel Briggs, a Parliamentarian who had besieged his house. A century later, on Midsummer’s Eve in 1745, 26 respectable witnesses saw a Jacobite army on Souther Fell, a place no force could possibly have been, a fata morgana for a time of anxiety.

But in April 1778, there was an actual incursion, when John Paul Jones landed at Whitehaven—a ship-building, trading, and whaling port linking the “Three Kingdoms” of England, Scotland, and the Isle of Man—with 30 men from the U.S.S. Ranger. He hoped to torch hundreds of ships as they languished at low tide, crammed in tightly between the piers. But the wind was against them, and the sky was already paling when they made landfall. Jones and his party landed at the southern fort and spiked its cannon, while half of his force went to the northern part of the harbor to set the ships alight. The latter resorted to a public house, ostensibly to get a light for their incendiaries, but seem to have been sidetracked by the stock. When Jones rejoined them, he found no ships had been burned because no one had a light. Even when they finally obtained one, their arsons went awry, most of the fires fizzling out, and others quickly extinguished by locals—who had been alerted by a Ranger crewman apparently anxious about anyone getting hurt. Jones withdrew ignominiously, taking just three prisoners and leaving behind a few hundred pounds’ worth of damage, and a reputation as dastardly pirate. (The town pardoned him only in 1999.) The seriocomedy continued as he headed to Kircudbright to kidnap the Earl of Selkirk, only to find him away from home, meaning Jones had to make do with the family silver, including Lady Selkirk’s still-hot teapot, which she gave up after a short but probably strained interview.

This was also a District for criminals, the Lancaster assizes passing more death sentences than anywhere else in England between the mid-18th and mid-19th centuries; about 265 were hanged in the castle’s “Hanging Corner” between 1782 and 1865. (The assizes also covered Manchester and Liverpool.) Smuggling was common, and a hint of old watchfulness can be gleaned at Roa Island, reached by a narrow Victorian causeway just above the water, and sometimes below it, flanked by salt marsh with a beached trawler and lifeboat, and a dinghy tied to a garden wall. At the end of the causeway rises an early Victorian inn and a thicket of masts, cannon pointing out to sea, and the “Gothick” archway of an excise house framing the channel, and ships and submarines heading into Barrow-in-Furness. Just off Roa is the ruined Piel Castle on Piel Island, an outpost of the English Church Militant, built by the Abbot of Furness to guard against Scottish raids.

Another instance of old interest in this area is the extant post of Guide to the Queen’s Sands, which has existed since 1538, a post-Dissolution assumption of an old monastic responsibility. The Duchy of Lancaster pays the Guide a nominal £15 per annum (plus rent-free use of a 12-acre farm) to lead travelers across Morecambe Bay at low tide. Until the railways came in the 1860’s, this was an important route, but it was always hazardous—crossing 120 square miles of mudflats, where the rivers Keer, Kent, Leven (there is a separate Guide to the Leven Sands), Lune, Ribble, and Wyre commingle in shifting quicksands and racing tides. As recently as 2004, 21 illegal Chinese cocklers were cut off and drowned—victims of exploitation as much as the early 18th century Sambo, “a faithful negro, who, attending his master from the West Indies” died at Sunderland Point near Lancaster, and was buried out under the sands. The present Guide, fisherman Cedric Robinson, appointed in 1963, has occupied the position longer than any of his 24 precursors. Seeing pictures of him in action, probing with his tall staff while throngs wait for his word, one thinks of ancient images—St. James and scallops, fishers of men, finders of The Way.

Back on terra (very) firma, the area’s farmers have always scratched subsistence from soil lying like the thinnest of coverlets over rock, their farms surviving only with subventions. The last English wolf was supposedly killed here in 1390. Below the farmers’ angled, drywalled “pastures” and “yow” pens, the ancient peddler tracks and corpse-roads over the tops and down into Yorkshire, lie thick coal seams, mined from the 13th century, and in 2017 being revived after a decades-long hiatus. Whitehaven was epicenter for an industry that brought crucial employment, with some mines stretching miles out under the sea, but also multiple disasters. The pits at Whitehaven, says the Durham Mining Museum, have “probably the blackest record in the annals of coal mining.” The 20th century bears grim testament. In 1910, 136 men and boys were killed in a single explosion. In 1922, there were 39; in 1928, 13; in 1931, 27; in 1941, 12; and in 1947, 104. The 1910 explosion was the biggest mining disaster in the history of the county, and 64 Edward Medals were awarded to rescuers, the most ever for one incident. Details still stab; when the mine was unsealed after four months so bodies could be recovered, one corpse was found cradling his teenage son and his son’s friend in his arms. Another man had taken off all his clothes and folded them beside himself, insufferable heat not preventing neatness. They also found chalked messages showing some had survived the explosion, to sign off miserably afterward in stifling, Stygian timelessness.

While men lived like Morlocks below, far above tramped self-exiles and sensation-seekers, reveling in the area’s otherness. These men were as different from miners in expectations and outlook as Keats, whose abandoned Hyperion references the prehistoric Castlerigg stone circle near Keswick:

Scarce images of life, one here, one there,

Lay vast and edgeways; like a dismal cirque

Of Druid stones, upon a forlorn moor . . .

Then there was Ruskin, looking out from the turret of Brantwood in search of impressions; Turner, trying to capture particular lights on particular stones before all colors altered; Aleister Crowley, an unexpected alpinist, disdainful of the rising generation of “rock gymnasts” he ironically despised as self-publicizing; Arthur Ransome, Soviet-sympathizing author of the so-British, so-bourgeois Swallows and Amazons books; and Donald Campbell, who died on Coniston Water in 1967 while trying to set a world water-speed record in Bluebird K7. (His body was found in 2001, and his head is still missing.)

Another Lakes-lover was Alfred Wainwright (1907-91), son of a stonemason from Blackburn, who succumbed to the fells’ spell on June 7, 1930, staring out from Orrest Head, above Windermere:

I was totally transfixed, unable to believe my eyes. . . . I saw mountain ranges, one after another, the nearer starkly etched, those beyond fading into the blue distance. Rich woodlands, emerald pastures and the shimmering water of the lake. . . . this was real. This was truth. God was in his heaven that day and I a humble worshipper.

He spent much of his remaining 61 years tramping the fells’ every inch, like them externally forbidding, describing and drawing his routes in seven Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells, now standard reference works—each dedicated unusually, such as “The men who built the stone walls” or “Those unlovely twins, my right leg and my left leg.” When his eagle eyes failed in old age, he found himself “in a grey mist,” like those he had seen so often descending over arêtes and peaks, seeing maps increasingly only in mind’s eye. In his posthumously published Memoir of a Fellwanderer, he wrote wistfully of a final walk, slipping and stumbling in rain on an ascent made often before—of how his “silent friends . . . shed tears for me that day.”

Some northwesterners sought escape rather than entrance, like John Barrow (1764-1848), knighted son of an Ulverston tanner. His career encompassed whaling in Greenland, comptrolling in China, auditor-general of the Cape Colony, permanent secretary to the admiralty, promoter of Arctic exploration (Alaska’s Barrow was named after him, in 1825; since 2016, it is officially Utqiagvik, emblematic of ongoing de-Englishing), and president of the Royal Geographical Society. His Monument, a replica lighthouse, crowns Hoad Hill over his hometown, offering aptly vast maritime and montane panoramas.

Another Lakes-forsaker was Stan Laurel, born Arthur Stanley Jefferson in Ulvers ton in 1890, to a vaudevillian family. Brats, Tit for Tat, Saps at Sea, Way Out West, and all the rest play on continuous reel at the town’s Laurel and Hardy Museum, as visitors roll around reminded of the boys’ brilliance, or inspect the photographs, typescripts, bizarre L. & H. merchandise, and things young Stan knew, including a mangle from an outhouse where he spent hours in punishment for high-spiritedness. Yet while Santa Monica became Stan’s residence, and his Englishness a comic prop, part of him always looked homeward. He took Ollie there in 1947, and Ollie told the North-West Evening Mail, “Stan had talked about Ulverston for the past 22 years.”

We, too, will return, cured at last of anti-Lakes ennui, old ideas augmented by new lights—“England’s Switzerland” under an azure empyrean, blood-warm walls, Whitehaven cormorants holding out wings toward the Kingdom of Man, the sun declining superbly over a stupendousness of slopes, thickly treed hillsides tumbling down to lakes like mercury, black-faced sheep on bald sides leading up to incomprehensible viewpoints.

Leave a Reply