The present condition of literature (as that term is ordinarily understood), at least in America, is obviously unhealthy. Its illness is the result not only of internal undermining, “the invisible worm” of Blake’s “The Sick Rose,” but of external conditions, the “howling storm” on which the worm (however implausibly) rode. External and internal decline, all too visible in this case, go together, of course. While they can be traced partly to the enormous social and cultural changes of previous centuries, they are principally a mid- and late-20th-century development, involving separation (or “alienation”) of good readers from good writers, then decreasing numbers of both. Earlier, belles-lettres were meaningful, as well as vigorous and popular, on both sides of the Atlantic. Mass magazines in America gave considerable space to elite forms of literature, including poetry, as well as more popular forms, both of which nourished “parlour literature”—the practice of reading at family gatherings. Charles Eliot Norton reported in the 1890’s that there were Dante reading clubs from the Atlantic to the Pacific. In 19th-century France, Alphonse de Lamartine could reply to a detractor that his new book of verse would soon be in every cobbler’s pocket. The poems of Victor Hugo, from his odes at age 20 to The Art of Being a Grandfather, 55 years later, were read widely, not of course by those with no schooling, but often by those with little. His serialized novels had vast audiences, and not just in Europe; American poet and critic Morris Bishop told how his father’s family waited impatiently for each new episode to arrive in the mail. Now, in contrast, poetry no longer belongs to the mainstream, as Dana Gioia observed, too gently, some years ago in the Atlantic Monthly, and fiction has been largely degraded.

Among contemporary conditions favoring the decline of literature, in addition to critical theory (to be discussed shortly), are the dominance of popular culture, low moral standards, and erosion of language (all connected). Popular culture, spread by every medium, drives out better creations, as, according to Gresham’s Law, inferior products, if they reach what is now termed “critical mass,” usually do to superior ones. Instead of being confined to undiscriminating readers, like dime novels or what the French call “train-station literature,” inferior writing has usurped the place of good in the marketplace and is even admired by some who should know better. Such vulgarized writing is now the principal, sometimes the only, interest of countless editors and publishers (the latter, with exceptions, large conglomerates uninterested in quality). Popular culture has been legitimized, placed on a footing with, or rather elevated above, high culture; at a nearby state university, a course on rock ’n’ roll is accepted for elective credit in a liberal-arts curriculum that lacks any foreign-language requirement. (Far more offensive examples could be cited.) Degraded moral standards allow for the crudest material to enrich its creators, even—in the case of so-called art—be subsidized by tax dollars, through moral indifference or, worse, as direct defiance, and without any acknowledgment that such degradation is a violation of human dignity. As for language standards, consider what you hear from television news; even the New Yorker, once known for its rigorous standards of English, now allows its journalists to use routinely such barbarisms as “It is him.” Maybe even the editors do not know better. To ungrammatical language is added the filthy talk that used to be associated with fishwives and sailors. The meaning of words is so adulterated that the word artist is now applied to such as Britney Spears and Michael Jackson. Style, in the sense of good style, has been so devalued that those who esteem it are condemned as offensive snobs. Though novelists, playwrights, and poets can blame society for abandoning standards of good taste and the ideal of lasting literary value, they, too, are responsible, as they adopt shamelessly the worst demands of publishers or producers. (Look at Larry McMurtry.)

Others who have sabotaged literature are the critical theorists. Now, theory need not be a literary Fifth Column. For instance, Theory of Literature (1949) by René Wellek and Austin Warren had as its aim not dismantling literature but clarifying literary values and what can be known of the creative process, along with proposing strategies for analysis and judgment; and, while certain approaches there reflected changed modes of thinking, masterworks remained honored, not undermined. Well over half of Hazard Adams’ massive anthology Critical Theory Since Plato (1971) is devoted to canonic critics who wrote generally in support of the literary enterprise, though a few might be surprised to see how their thought is interpreted. In contrast, Adams’ and Leroy Searle’s 1986 anthology, Critical Theory Since 1965, includes mostly contemporary writers hostile to conventional literature, many of them foreign thinkers who directed their critical aggression against America (while often accepting her dollars). Here, the word critical no longer refers to “criticism” in the broad sense, as Aristotle, Horace, Sidney, Addison, Schlegel, Coleridge, and innumerable others practiced it, but, chiefly, to radical cultural critique (hence the proximity of “cultural theory” and “critical theory”) and deconstruction based on revisionist history, linguistics, sociology, and other disciplines in their postmodern stages. Therein lies the difficulty.

What is meant by the term postmodernism can be defined roughly, with respect to literary criticism, as denying, on several grounds, the claims of literature (nonradicalized) to prima facie truth and meaning, values of taste and beauty, and the worth of writing from privileged groups, considered oppressive. The great modernists such as Eliot, Yeats, and Proust still believed in words (and art) and their connection to the real; new ways of employing them were still art and were valuable. Proust believed only in words. The meaning of a work could be chiefly its beauty, or its truth, or both; it could be lyrical, dramatic, narrative, meditative, satirical; but it was still meaning. Even the Surrealists believed in language. The “tradition” was honored, if obliquely. As Pierre Albert-Birot wrote in a manifesto of 1916, anticipating the movement:

The French Tradition: is to break the shackles

The French Tradition: is to see and understand everything

The French Tradition: is to search, discover, create . . .

Therefore the French Tradition IS TO NEGATE TRADITION

Let’s follow the tradition. . . .

But that was still predicated on the function of language as conveyer of meaning: Words meant what they said, even if antiphrastically; whereas the strain of postmodern criticism for which the late Jacques Derrida deserves credit, along with long-deceased linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, denies the capacity of language to hold and transmit meaning. Words are unstable, indeterminate, without intrinsic connection to what they stand for, and always defined by other words; all statements can always be deconstructed. (Belief in the Word is obviously excluded.) Perfect logic cannot be achieved in language (the old Cratylist complaint, illustrated by the paradox “All statements are false”). Meaning is endlessly deferred.

Derrida denied, by the way, the near-nihilism that his position constituted. Shortly before he died, he said that philosophy had been for him “the search for an ethos and a way of life.” However lofty that aim may sound, his influence was nonetheless nefarious. That anyone should read literature or anything at all, except for the pleasure of deconstructing it, contradicts his theses, of course; but the latter constitute an impracticable extreme, a meta-criticism (as he might say); even he used words to question them. In practice, his denunciation of the power of language to denote the real and the true is, along with other theories, called into service normally to attack the truth-value of canonic literary and philosophic works.

A second claim connected to truth-value is that, since all writing consists of words used by others and, thus, relates to other texts in endless intertextuality, the writer is merely reshuffling no one’s material. There is no authority; there is no author. If you add a further claim, familiar since Freud’s ideas were popularized, alas, in Europe and America, to the effect that the self is not only in perpetual conflict but the plaything of unconscious, uncontrollable drives, and therefore is not the rational, aware being that would engage in controlled literary creation, you have all you need to question the value of literature as it was heretofore understood.

Or almost everything. For there is also the multiculturalist claim that Occidental literature must be rejected because of its privileged social origins and practice. The “Dead White Male,” whose products are racist, sexist, elitist, rationalist (analytical, “vertical” rather than “horizontal”), and deliberately oppressive (whether he knew it or not), and who excluded the “marginalized” except in rare circumstances, is a monster who, having terrorized the past, must now be slain. Since one blow does not suffice, the attacks remain ongoing. Four veins of thought (all well represented in the Adams-Searle anthology) have contributed to this new dogma: Marxism, with its theory of social classes and economic exploitation; post-Marxism, which adds to economic and class theory that of the formative, oppressive role of cultural products, structures, and institutions (Michel Foucault’s credo); radical feminism, with its hatred of male achievements and deliberate discounting of historical conditions that shaped past customs; and postcolonialism, with its victimology and resentment of the West. According to enthusiasts of this thinking, the literature that originated among and was practiced by those in power is necessarily oppressive and “inauthentic,” as Marxists would say. Aesthetic criteria and values are rejected; refined style is deemed exclusionary, false; good taste constitutes shackles. Even the venerable genres are viewed as tyrannical. Only new writing, by those who denounce analytic reason and adopt an adversarial relationship to past or present (postcolonials and other dark-skinned peoples, women, prisoners, homosexuals and other deviants, and the acolytes of all of these) is viewed as legitimate. (Here is where those who believe the world can be changed by writing—the old-style revolutionaries and new activists—part company with those more radical thinkers who question the efficacity of language.)

It may be asserted that, whether critical or creative, the new multiculturalist writing constitutes a valuable creative élan. Just as earlier generations pushed the boundaries, “negated the tradition” or, as Jean Cocteau wrote, tried to see “just how far you can go too far,” the formerly marginalized and their apologists, the new critical theorists, push back the frontiers; they are literature’s astronauts. Perhaps. Certainly, from the Greeks on, writers have displeased traditionalists by breaking molds, and daring products of literary evolution may, after a period of incomprehension, be viewed as masterpieces rather than as provocations. Euripides overturned certain conventions of his predecessors and was considered disturbing. Victor Hugo shocked critics by dividing, through caesuras, the alexandrine line of twelve syllables into three groups (4/4/4) instead of the usual two (6/6). His innovations on the stage—scenes by torchlight, amours between a servant and a noble, characters of grotesque physique or monstrous soul—were deemed still worse. Flaubert was put on trial for Madame Bovary; certain poems by Baudelaire were condemned in court, and the author, fined. No matter: Romanticism assimilated these innovations and disturbing materials and countless others until they, too, became literary commonplaces and were extended or replaced.

Current critical theory is different in kind, however, since it, first, denies value ipso facto to creations by members of condemned groups (or holding forbidden views—think of how Eliot is regarded by cultural critics); second, subverts belief in truth and meaning by challenging the ability of words to refer to and convey, in any sense, the real; third, attacks values of taste and beauty; and, fourth, undermines the ideal of the learned man. The last enterprise may be the worst, since, armed with learning, one could see through the others.

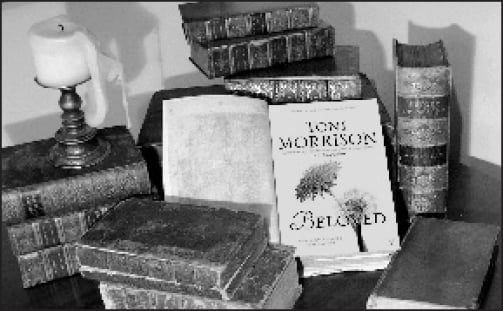

The most deplorable thing is that, in the general remove of literary culture from the public forum (there are hardly any independent critics nowadays), these critical sophists have come to dominate the academy, the locus of such literary education as American youth get. Postmodern thinking appears to have filtered down to many high schools, and no university offering graduate studies in literature is without courses in critical theory, supported sometimes by a disproportionate number of faculty positions, plus lectures and workshops. One wonders, nevertheless, how many students and even faculty read the turgid prose of its practitioners, which, at its worst, is gibberish. (Well, some of my graduate students did not read assignments given by colleagues, I know.) There are further consequences. Since analytical thinking, the characteristic mode of Occidental men, is considered oppressive, and organizing literary study by language or territorial division reflects, it is asserted, oppressive structures and “opaque” social relationships, there has been a concerted effort to break down departments, curricula, and syllabi organized rationally (by language, genre, or chronology). Anyone can teach almost anything, preferably something unconventional, in any context. A Wesleyan University (Connecticut) faculty member writes in the American Scholar (Winter 2005) that one student was assigned Toni Morrison’s Beloved in all four courses he took one semester. Chronology is especially despised—a symptom of postmodernist scorn for history; dates are viewed as irrelevant. When students objected, on grounds of historical usage, to a famous professor’s sexual interpretation of the word screw in an Emily Dickinson poem, he retorted that the author’s meaning was immaterial.

Not all contemporary modes of criticism are so destructive as what has been sketched here; certain approaches, such as narratology (a way of analyzing plot) and reader-response criticism—emphasizing the context of reading—extend commonsensical understandings from the past, which, rephrased and refocused by discerning critics, may lead to a finer understanding of how literature works. They are tools, not dogma. Restating that which “oft was thought” in an altered light can be useful. Circumstances have changed; there are new readers, new works, and new ways of looking at old ones. But denying the foundations of past achievements is unjustified. And no criticism should take the place of the literature it is supposed to serve. The reading lists of the past have not been merely revised; they have, in some quarters, nearly given way to criticism on authors once read firsthand. Critical theorists are something of a priestly caste, holding arcane secrets, with the power to validate or invalidate our reading. If we can be initiated into their obscure jargon, we, too, can penetrate their esoteric truths and be saved.

Literature still matters, nevertheless, and its American audience, though small, could be cultivated and enlarged by devoted publishers and proper curricula in colleges. Its traditional uses and pleasures (“plaire et instruire,” wrote Boileau in his Art poétique, following Horace) remain valid. To portray, examine, and reflect on life, in general terms (as done by the most philosophic writers) or from the individual viewpoint (the more characteristic literary approach); to enrich experience or add to it; to propose ways of being, seeing, knowing; to offer justification and judgment, especially warnings against self-infatuation, and explore the possibility of the moral life—those have been the functions of good writing since the Greeks replaced myth, which functioned somewhat similarly, with rigorously formal, highly reflective modes. By requiring shaping, condensing, focusing, reflection, literature stylizes life, multiplies it, and broadens understanding of ourselves and others, whose innermost emotional and intellectual experiences are made available to us. (To know them thus is voyeurism only to those who make it so; properly, it is sharing in their humanity.)

Good taste is not, of course, always imperative. Was Rabelais refined? Is the Porter’s scene in Macbeth in good taste? The coarse, along with the delicate, and evil, with good, are part of the real and, hence, of literature; but, in the Occidental literary tradition, the offensive is not a model, and corrective values are always visible, sometimes juxtaposed. To wallow in disgust and invite others to do so cannot be the purpose of literature. As Chilton Williamson, Jr., pointed out in his review (“No Country for Anyone,” April) of Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men, even McCarthy, often the painter of the most depraved, the least redeemed of human beings, works into his novels a moral dimension, barely glimpsed but thereby all the more crucial.

Literature always points to something beyond itself, a pleasure, verity, judgment, vision. It is more than rewarding; it is essential. The modernists recognized these truths. Wallace Stevens observed, “The pleasure of poetry is to contribute to man’s happiness.” William Carlos Williams, in one of his last poems, “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower,” wrote:

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

Richard Eberhart, of a younger generation, said in a 1968 speech: “The point of poetry is to make meanings for your life, to discover durable truth of yourself within the flux of life and time . . . Poetry defends the inner capacities of man.”

Belles lettres can make another contribution: Rigor in language both reflects and leads to rigor of thought, surely an urgent national need. That is, reading the best of what has been written cultivates discrimination. Consider the gullibility of the American audience and today’s cultural fare, which the media reinforce or create: government pronouncements, “studies” (sociological, psychological, quasimedical, all purportedly scientific), commercial advertising, tendentious publicity and undertakings of not-for-profits, including universities and museums, live drama, film, all reinforced and publicized by print journalism and television. What is, at face value, information with the presumption of truth or, in the case of entertainment, is taken as normative is, in fact, frequently misleading (often deliberately), manipulative, corruptive. The cultivation of good literature now and study of great works of the past (along with philosophy and history) could provide means to identify and resist what is false and depraved. Perhaps Ezra Pound, Vorticist, crank, asylum inmate, but wise in this respect, should have the last word: “If a nation’s literature declines, the nation atrophies and declines.”

Leave a Reply