Is the Ashcroft Justice Department busily engaged in shredding the Constitution under the cover of September 11? We are, the President tells us, at war, and in war, we are often told, the first casualty is civil liberties. Some feared that this was the case when Attorney General John Ashcroft, in July, unveiled his TIPS plan (“Terrorism Information & Prevention System”). TIPS was designed, as Business Week’s Jane Black explained, to use “your cable guy, meter reader, even your postman to voluntarily [sic] report any and all suspicious information about you to a new, central FBI database”—the better to ferret out future Muhammad Attas.

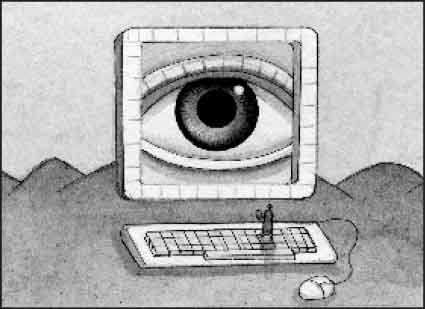

Enlisting these service personnel was thought to be a way to conduct household searches without obtaining a warrant, thus making what celebrated Boston “civil-liberties lawyer” Harvey Silverglate called “an end run around the Fourth Amendment.” The horror generated by TIPS was instantaneous and virtually universal, and, within a scant few weeks, the program appeared dead when Congress prohibited any “national snitching programs” (as Slate reporter Dalia Lithwick called them) in the draft of the as-yet-unpassed Homeland Security bill. The ACLU had been predictably shrill; legislative counsel Rachel King warned that “Law enforcement may end up chasing information based on uninformed citizens who have their own biases or may be prejudiced.” At a Senate hearing, Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-UT) said that “We don’t want to see a 1984 Orwellian-type situation here where neighbors are reporting on neighbors.” Woody Harrelson, the Hollywood actor most noted for his portrayal of what London’s Daily Mirror called “the dim barman” in Cheers, said that “The war against terrorism is terrorism. The whole thing is just bullsh-t.”

Eternal vigilance, the cliché has it, is the price of liberty, and congressional vigilance may have saved us from TIPS, but was this too little, too late? In the wake of September 11, with almost no dissent (the House vote was 356-66, the Senate vote, 98-1), Congress passed, and the President signed, the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act (“USA PATRIOT Act.”) Its chief architect was U.S. Assistant Attorney General Viet D. Dinh, a former prominent member of the Federalist Society, former law professor at Georgetown, and former clerk for Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor (and a possible future first Asian-American appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court under a Republican president). The PATRIOT Act, Mr. Dinh explained in a speech to the District of Columbia Bar Association, was no more than a simple means of preserving the “ordered liberty” beloved of Edmund Burke, by “updating the law to reflect new technologies.” Al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden, Mr. Dinh noted, were taking advantage of modern means and so should the Justice Department, since “Knowing what we now know about al-Qaida, it is easy to see that its radical, extremist ideology is incompatible with, and an offense to, ordered liberty.” “Al-Qaida seeks to subjugate women; we work for their liberation,” Mr. Dinh told the Washington lawyers. “Al-Qaida seeks to deny choice; we celebrate the marketplace of ideas. Al-Qaida seeks to suppress speech, we welcome open discussion.”

Accordingly, for the first time, the USA PATRIOT Act permitted the CIA and the FBI to conduct domestic surveillance by performing, in Mr. Dinh’s words, “online searches on the same terms and conditions as the general public.” It also “authorized the sharing of intelligence information across government departments so that we can compile the mosaic of information required to prevent terrorism.” Finally, the PATRIOT Act spelled out new authority for detaining suspicious characters. As Mr. Dinh put it, “Any infraction, however minor, will be prosecuted against suspected terrorists.” This implied that the prosecutorial discretion of the Justice Department was to be employed in order to “remove from our streets those who would seek to do us harm,” but Mr. Dinh was at pains to point out that this was not “preventive detention,” even though the European Convention on Human Rights (to which, of course, the United States does not subscribe) “allows states to subject a person to preventive detention ‘when it is considered necessary to prevent his committing an offence.’”

Mr. Dinh claimed that the Justice Department had “taken every step at our discretion, used every tool at our disposal and employed every authority under the law to prevent terrorism and defend our ordered liberty.” He sought to calm possible fears on the part of the D.C. Bar, assuring them that “We have done so with the constant reminder that it is liberty we are preserving and with scrupulous attention to the legal and constitutional safeguards of those liberties.” Indeed, he added, Attorney General Ashcroft’s “charge to the Department after 9/11 was simply: Think outside the box, but never outside of the Constitution.” Less than reassured, John Seiler, in the same edition of the Orange County Register in which Mr. Dinh’s speech was published, complained that “Alleged terrorist Jose Padilla, a U.S. citizen, is being held without charges, in violation of the Fifth Amendment right to ‘due process’ and the Sixth Amendment right ‘to be confronted with the witnesses against him’” and that “Vast new powers to snoop and arrest have been advanced” under Ashcroft, including a proposed “Cyber Security Enhancement Act,” which would allow “e-mail snooping without a search warrant, in violation of the Fourth Amendment.” Seiler quoted Rep. Bob Barr of Georgia (one of the Republican managers of the Clinton impeachment effort), who had charged the Bush administration with “a massive suspension of civil liberties in a way that has never been done before in our country. These changes are so vast and fundamental [that they] will likely set precedents that will come back to haunt us terribly.”

There have not yet been many judicial examinations of the administration’s antiterrorism measures, but one occurred in the court of Clinton appointee Gladys Kessler, U.S. district judge for the District of Columbia, whom the Wall Street Journal calls “a famous liberal.” Following the policy Mr. Dinh outlined, the federal government detained some 1,182 persons, all foreign nationals, without publicly disclosing the names of the detainees. Sensible people should have wondered whether this indicated that something is wrong with our immigration policies; instead, the chattering classes nattered about what this portended for civil liberties. Former Clinton secretary of state Warren Christopher, for example, compared the fate of these alien detainees to Argentina’s “disappeareds.”

Unlike the disappeareds, however, most of the detainees were released, so that, by the time Judge Kessler issued her opinion on August 2, probably fewer than a quarter of them were still in custody. These included 74 people charged with violating immigration laws, 73 accused of violating some other federal law, and an undisclosed number under lock and key as material witnesses in terrorism cases. The American Civil Liberties Union, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, People for the American Way, the Nation, and 17 other “public interest organizations,” as Judge Kessler called them, brought a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) proceeding demanding that the government release the names of all of those detained, the circumstances of their detentions or arrests, the nature of the charges filed against them, the identities of their lawyers, and other information, including any “policy directives or guidance issued to officials about making public statements or disclosures about these individuals.” Precisely why these “public interest organizations” wanted this information was unclear, although some suggested that they were seeking to find out whether the government had used “racial profiling” in the course of the arrests and detentions.

The government fought the disclosures on the grounds, among others, that FOIA exempted the release of information that could “reasonably be expected to interfere with [criminal law] enforcement proceedings,” “could reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy,” or “could reasonably be expected to endanger the life or physical safety of any individual.” The government argued that to release this information would give the nation’s terrorist enemies too many clues about how much we knew and when we knew it, allowing them to put bits and pieces together to create a “mosaic of information” of the type Mr. Dinh had said the government itself was building. To release such information would also put the families of detainees at risk of possible terrorist retaliation and would subject the detainees, their families, and their lawyers to public scorn or danger from Americans who might suspect them of complicity with the terrorists.

Judge Kessler was persuaded that law enforcement might be compromised by revelation of the details and circumstances of the detainees’ arrest and detention, but she ordered the names of the detainees and the names of their attorneys immediately released and found that the government had not sufficiently searched their files to reveal policy directives that ought to be turned over to the “public interest organizations” under FOIA. Judge Kessler did rule that any detainee who requested it could keep his name secret (thus presumably avoiding the possibility of retaliation), but she was unpersuaded that the release of the names of detainees or counsel would compromise the government’s law-enforcement efforts or result in danger of retaliation to any detainee’s counsel. That last part of Judge Kessler’s opinion was particularly delightful; she observed that

lawyers are a hardy brand of professionals. The legal profession has a long and noble history of fighting for the civil liberties and civil rights of unpopular individuals and political causes, ranging from their advocacy on behalf of WWI dissidents, to their resistance to McCarthy era abuses, to the defense of persons accused of heinous capital crimes.

To the assertion made by the government that members of the public might “seek to retaliate” against detainees’ lawyers because they might be perceived as “working against the interests of the United States,” Judge Kessler proclaimed that “Not only is there no evidence of such retaliation, but the Government assumes, without any support, that citizens do not understand the role of defense lawyers in the American system of justice.”

In truth, the government’s aim in concealing the names and details of the detainees was not the protection of lawyers but the frustration of terrorists. Judge Kessler’s opinion was greeted with official dismay. Assistant Attorney General Robert McCallum said that Kessler’s ruling “impedes one of the most important federal law enforcement investigations in history” and that it “harms our efforts to bring to justice those responsible for the heinous attacks of September 11.” The New York Daily News, citing these remarks, stated in an editorial that Kessler’s decision was “dangerous” and that it “made it easier for Al Qaeda and friends to keep tabs on their operatives in the U.S. or at least to know whether their cohorts have been nabbed by the feds.” This, however, was an unusual press reaction, as virtually all of the commentary immediately following the ruling praised Kessler for striking a blow for liberty.

A week after Judge Kessler’s ruling, the administration appealed it to the D.C. Circuit, indicating that the judge had, in the words of the AP, “missed the point about keeping the names secret.” The Wall Street Journal predicted that Kessler’s ruling would not survive appeal. (I am not so sure.) What her decision probably means is that the more adventurous parts of the USA PATRIOT Act and any Homeland Security Act are likely to have a difficult time withstanding court challenges. Indeed, any future actions on these matters brought in the Federal District Court for the District of Columbia are likely to be assigned to Judge Kessler, on the grounds that she is now more familiar with the issues involved. This is suggested by the fact that Kessler was also assigned the case brought by the Holy Land Foundation for Relief and Development (“the nation’s largest Muslim charity,” according to ABC News), protesting its designation as a “terrorist group” and the seizure of its assets by the U.S. government. In that case, Kessler gave what ABC called “a sweeping victory to the U.S. Justice Department.” She ruled that “Both the government and the public have a strong interest in curbing the escalating violence in the Middle East and its effects on the security of the United States and the world as a whole” and, further, that the government’s tactic in taking control of the foundation’s assets was “an important component of U.S. foreign policy, and the President’s choice of this tool to combat terrorism is entitled to particular deference.” However, Kessler allowed the foundation to proceed to trial on its claim “that the government’s entry onto its corporate premises and removal of its property without a warrant violated its constitutional right against unreasonable search and seizure.” Still, she acknowledged that “the government advanced strong arguments in support of its position defending the search and seizure,” perhaps hinting that the ultimate ruling even on this issue would favor the Justice Department.

There are those who believe that the United States and, indeed, the world were irrevocably changed by the events of September 11, but a federal bench with great discretion to protect what it deems “civil liberties” and to favor “public interest organizations” was certainly left unchanged. Judge Kessler’s somewhat inconsistent rulings—some favoring the government, some favoring “civil liberties”—do nothing if not demonstrate the great discretion she and other federal judges have in interpreting the Constitution. The Constitution only protects against “unreasonable” searches and seizures and only requires “due” process. But who can say what is “reasonable” and what is “due” when we are dealing with lunatics bent on our destruction who believe that, by obliterating themselves as they fly jetliners into tall buildings, they will be guaranteed mansions in paradise inhabited by 70 doe-eyed virgins?

Both the “public interest organizations” that brought suit in Judge Kessler’s court and the Ashcroft Justice Department claim a commitment to the Constitution. In Mr. Dinh’s speech to the Washington lawyers, he made reference to Benjamin Franklin’s “now-famous statement, that ‘They that can give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety’”; he then argued, however, that, unless security can be maintained, there is no hope for liberty—and he is surely correct. Perhaps it is significant that, since September 11, there has not been another large-scale terrorist strike against the United States, and our freedoms have not evaporated (except, perhaps, at our airports). If either of these situations changes, it is doubtful that the courts can do much about it. Litigation has too often been the tool of choice for those seeking political or cultural change, but, as the varying results produced in Judge Kessler’s court show, it is an uncertain enterprise when dealing with national security and terrorism.

Perhaps that is at it should be. If the Bush administration and the Ashcroft Justice Department are effective in protecting us from those who would seek to destroy us and in preserving ordered liberty, we ought to be able to judge for ourselves, just as we ought to be able to discern their failure. We have means through the ballot (or even through impeachment) of replacing the government if it acts contrary either to our wishes or to our Constitution, and that, rather than recourse to the courts, is probably the best means of preserving liberty.

Leave a Reply