“Remember Pearl Harbor” was a phrase familiar to everyone I knew growing up. In a sneak attack, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor! This was a dastardly, despicable act. A sneak attack! The politically correct today like to say “surprise attack,” but that is something done in time of war. The Japanese attacked without a declaration of war. Dirty, craven, unforgivable. The Japanese thought their sneak attack was clever, daring, bold. They were going to knock us out of the war before it began. We were a threat to their dreams of conquest on the Asian mainland and in the Pacific. What better than a preemptive strike? It was not without precedent. The Japanese had launched a sneak attack against the Russian Pacific fleet at Port Arthur on the Liaotung Peninsula in Manchuria in 1904. The similarities between Port Arthur and Pearl Harbor are eerily striking.

Although President Franklin D. Roosevelt may have had different ideas, the American people wanted nothing to do with the war in Europe or in China until Pearl Harbor. Gallup started taking their first polls in the late 1930’s, and consistently—right up until December 7, 1941—70 percent or more of the American people wanted no American involvement in Europe or the Orient. From 1935 through 1939, Congress passed a series of Neutrality Acts, signed by the President, that, among other things, forbade the sale or transport of arms or munitions to a belligerent, private loans to a belligerent, and the entry of American ships into war zones. However, when Germany attacked Poland, President Roosevelt saw an opportunity to compromise American neutrality. On September 21, 1939, while the Germans were consolidating their gains in the western half of Poland and the Russians were attacking Poland from the east, Roosevelt addressed a special joint session of Congress, asking that the Neutrality Acts be amended to allow Britain and France to obtain war materiel on a “cash and carry” basis.

Not without a fight and considerable public comment, a bill worked its way through Congress and, on November 4, was passed to become the Neutrality Act of 1939. An even more intense fight developed over the Lend-Lease bill, introduced in Congress in January 1941. The bill would give the President the power to send foreign aid to our allies in the form of materiel and food. For two months, the debate raged. The passage of the bill, argued Sen. Burton K. Wheeler, a Democrat from Montana, “will plow under every fourth American boy.” Testifying before the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee, Charles Lindbergh said, “I oppose aid to England that would weaken us or carry us into the war. I don’t believe the United States can or should police the world.” The bill finally won approval in Congress during March, but House Republicans voted 135-24 against it.

Meanwhile, between the passage of the Neutrality Act of 1939 and the Lend-Lease Act of 1941, Congress approved the Burke-Wadsworth Act, the first peacetime conscription law in U.S. history. Introduced in the Senate in June 1940, the first draft of the bill required registration for all men 18 to 65 and essentially left length of service for those conscripted to be determined by the government. The sweep of the bill sparked widespread opposition. Senator Wheeler declared the bill the product “of a few people who want to see us go to war and send our youth to Asia and Europe.” Newspapers, magazines, and columnists joined the debate. H.L. Mencken editorialized against the bill; Walter Lippmann, who had applied for an exemption from the draft in World War I, was a vociferous proponent.

Week by week, the bill was reduced in scope until registration was required only for those ages 21 to 35; service was limited to one year; and draftees could serve only in the Western Hemisphere or in U.S. possessions and territories elsewhere. Even then, strong opposition remained in both the House and Senate, especially among Republicans. Sen. Hiram Johnson, a Republican from California and former governor of the state, declared the bill “a menace to our liberties.” In September, after more than two months of debate, the bill was finally approved by the House, 233-124, and the Senate, 47-25.

Men began being drafted, for 12-month terms of service, in October 1940. During summer 1941, the Roosevelt administration had Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall appear before Congress and argue that the draftees’ length of service should be extended. Conscripted soldiers were none too pleased. On the walls of barracks in dozens of Army camps appeared the chalked acronym OHIO: Over the Hill in October. In August, a draft-extension bill passed the Senate by a slim majority and squeaked through the House by one vote. President Roosevelt quickly signed it into law.

Desertions may have become a problem, but the Japanese sneak attack took care of that. Suddenly, men by the thousands were volunteering. On December 8, Congress declared war on Japan—not on Germany. The Krauts had not attacked us—the Japs had. Three days later, as required by the Tripartite Pact with Japan and Italy, Germany declared war on the United States. We then declared war on Germany. The sequence of events is not without significance. We did not go to war to save Europe or to prevent a pogrom of Jews or anybody else. We went to war because Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor. Only a small minority of Americans would have favored going to war for any other reason.

The sneak attack unified the nation and Congress as nothing else could have. Unlike the battles that raged over the Neutrality Act of 1939 and the Lend-Lease Act of 1941, the passage of a declaration of war against Japan was accomplished as soon as Congress convened on Monday morning, with only one dissenting vote. Jeanette Rankin, a Republican representative from Montana, declared, “As a woman I can’t go to war, and I refuse to send anyone else.” The Missoula-born Rankin was the first woman elected to Congress, winning a seat in the House in 1916. In 1917, she joined 55 other members of Congress in voting against a declaration of war, remarking, “Small use it will be to save democracy for the race, if we cannot save the race for democracy.” She did not return to Congress until 1941, just in time for her second negative vote on a declaration of war.

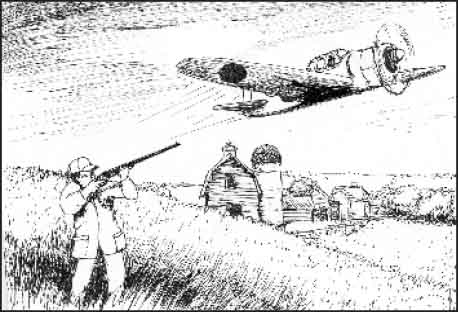

For several reasons, beginning with Pearl Harbor, the war in the Pacific has always fascinated me far more than the war in Europe. Although I was not born until more than a year after the war ended, my older brother was eight when the sneak attack occurred. He was helping our sister learn to walk at the time. My mother, father, and brother told me stories—and I asked that they repeat them again and again—about the moment they learned of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Unless somebody was alive at the time and old enough to appreciate the event, or knows someone who was, it is difficult for anyone today to understand the fury and rage that swept through America after the initial shock wore off. On the Pacific Coast, fear of a Japanese invasion was widespread. For many Californians, during the early months of 1942, it was not if but when and where. In Pacific Palisades, where my family lived, men and boys, carrying deer rifles and shotguns, patrolled the bluffs, night and day, and scanned the beaches and the sea for Japanese submarines and landing craft. Other men patrolled the streets at night, checking for light leaking from blackout curtains.

For America, the war started in the Pacific and ended there. When I was an undergrad at UCLA, several professors used their lectures to lament the very thing that ended the war, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. How different these views were from those of the American veterans of the war in the Pacific whom I came to know while growing up in the 50’s. To a man, they said, “The Japs started it. We finished it.” They were all ecstatic that the bombs quickly ended the war and aborted the planned invasion of Japan. This was especially true of Marine veterans of hellish island campaigns who experienced bushido—the Japanese warrior code of death before surrender—firsthand and of those sailors offshore at Okinawa who watched kamikaze pilots hurl themselves at American ships.

This was the America that I learned about—a country of reluctant warriors who were roused to fury because of a sucker punch. We were not militaristic by nature or imperialistic. However, when provoked, we fought like hounds from hell. We fought because we were attacked, and, because of that, our vengeance was righteous. During the last weeks of the war, Adm. William F. “Bull” Halsey was scavenging every bit of fuel and ammunition in the fleet for his carrier planes. When asked what he was doing, he replied, “I want to hit the Japs one more time—before they quit.” The Bull was a hero.

Most of us kids in the 50’s were superpatriots. We did not know it; we just were. We stood when the flag came by and put our hands over our hearts. We studied the Revolution and the Founding Fathers and drew the colonial battle flags. For us boys, the Gadsden flag, inspired by the first unit of Marines to serve, was our favorite. Featuring a coiled rattlesnake with the motto “Don’t Tread On Me,” it said it all for us. We saw every war movie two or three times when it was shown at our local theater and watched Victory at Sea over and over again on television. We proudly recited the Pledge of Allegiance and did not flinch when “under God” was inserted. This was probably because everybody went to church on Sunday. The only difference was which one.

With such a background, it came as a shock to me when I learned that President Eisenhower had lied to us. It was during the spring of 1960. I was in the eighth grade at Paul Revere Junior High School. Appropriately, our nickname was “Patriots.” Although we had done the quick-as-you-can under-the-desk missile-attack drill since grammar school, I spent little time contemplating the Cold War. I was busy drawing waves on my notebook cover and counting the days until summer. Like the Sirens calling Odysseus, the point at Malibu was beckoning all us gremmies.

On May 1, the Russians claimed they had shot down an American spy plane. President Eisenhower said that it was a weather plane, collecting forecasting data, which had strayed into Soviet airspace. “Yeah, the dirty lying Commies!” thought I. Then the Russians threw the trump card on the table. They had the pilot, alive and well, and the wreckage of the plane. The pilot was USAF Capt. Francis Gary Powers, on loan to the CIA. He was flying the Kelly Johnson-designed Lockheed U-2 spy plane at 80,000 feet over the Soviet Union when a newly developed Russian missile reached his aircraft. Powers was able to parachute to safety, but he had been unable to activate a self-destruct device on the plane. Nonetheless, we were not ready to fess up. A U-2 was rigged with weather-monitoring equipment and a fictitious NASA registration and markings and put on display at Edwards Air Force Base for the press. The Soviets countered by displaying enough equipment from Powers’ U-2 to end any doubt about its mission. Ike was forced to admit that we had a spy program of overflights and that Powers was monitoring and photographing Soviet installations.

I was stunned. My country was lying, and the Soviets were telling the truth. Ultimately, though, I became convinced that our prevarications and fabrications were necessary in the interest of national defense—necessary to protect American lives. Thanks to all the German scientists they had captured, the Soviets had a missile program second to none. All those under-the-desk drills were not about nothing.

The lie that put more than 50,000 American boys—or their body parts—in zippered plastic bags occurred four years later. During 1964, the United States began intensifying a program, a product of the CIA, know as 34-Alpha: the insertion of commando agents into North Vietnam to gather intelligence and to destroy various installations. At the same time, the U.S. Navy conducted “DeSoto” patrols in the waters off North Vietnam, both to support 34-Alpha operations and to gather electronic intelligence. On August 2, 1964, after 34-Alpha commandos had struck North Vietnamese installations at Hon Me and Hon Ngu, North Vietnamese patrol boats attacked a U.S. destroyer, U.S.S. Maddox. We were told that North Vietnam had launched an “unprovoked attack” against Maddox, which was on a “routine patrol” in the Gulf of Tonkin.

On the night of August 4, 1964, Maddox and another U.S. destroyer, U.S.S. Turner Joy, reported a second attack. This was some 17 hours after 34-Alpha commando raids at Cap Vinh Son and Cua Ron. Maddox reported radar contact with three or four vessels approaching at high speed. Curiously, Turner Joy made no radar contact. In support of the destroyers, the carrier Ticonderoga launched several planes. Visibility was poor, with intermittent clouds and thunderstorms. Although Maddox was now reporting that she was under torpedo attack, the pilots saw no enemy vessels and no wakes from torpedoes. One of the pilots was Comdr. James Stockdale, who was destined to be shot down in 1965 and spend eight horrific years as a POW and later be decorated with the Medal of Honor. “I had the best seat in the house to watch that event,” said Stockdale of that night in the Tonkin Gulf, “and our destroyers were just shooting at phantom targets—there were no PT boats there. . . . There was nothing there but black water and American fire power.”

Capt. John J. Herrick, a veteran of World War II and Korea and the skipper of Maddox, reported almost immediately after the incident that there probably had been no attack. The black night, stormy seas, unusual meteorological effects, and inexperienced and nervous crewmen, especially the sonar and radar operators, were responsible for a perceived attack. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara asked for clarification, and Herrick reported that he could not verify that an attack had occurred. Nonetheless, McNamara would tell Congress that there was “unequivocal proof” of a second “unprovoked attack” on U.S. ships, and Congress would obligingly pass the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. Meanwhile, President Lyndon Johnson, putting on his most serious and somber expression, went on national television and, while dozens of aircraft were launched from the decks of Ticonderoga and Constellation, explained to the nation that our ships had suffered an unprovoked attack and that he had ordered air strikes against North Vietnam. A little more than a year later, I joined the Marines.

Much later, we—the public—learned that there had been no attack. I am now beginning to fear that Saddam Hussein had no weapons of mass destruction—at least nothing that could threaten our national security. Did not President Bush tell us that the Iraqi dictator had a nuclear program that was less than a year away from producing weapons? Did not the President and Secretary of State Colin Powell tell us that Iraq had massive stockpiles of chemical and biological weapons? Were not the WMD’s the casus belli? It is difficult not to conclude that the Bush administration, heavily influenced by the neoconservatives (an oxymoron if there ever was one), is out to implement a grand geopolitical strategy to remake the Middle East. That is something that Alexander the Great did. Something the Romans did. Something Muhammad did. Something Britain did. Something empires do, not republics.

And who is to do it? Certainly not the neoconservatives. Do you think any of them could produce his DD214 for you? They use such terms as “moral clarity” and the need to project our power—but it is to be done with someone else’s body. A conversation I had with a budding neocon during a class discussion reveals their version of moral clarity. He did not seem to understand—and he is not alone in this today—that we entered World War II only because Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. Upon learning the exact circumstances of our entry into the war, he proceeded to argue that we should have gone to war irrespective of Pearl Harbor, to save the Jews in Europe. I then asked him if we should go to war whenever a particular group of people is being persecuted or killed. He replied, emphatically, “Yes.” Well, then, asked I, should we have gone to war against Turkey in 1915 to save the Armenians—a million of whom were killed—or against the Soviet Union in 1933 to save the Ukrainians (several million or more of whom were liquidated)? He seemed stumped.

I then asked exactly who was included when he said “we.” He looked at me as if I were a bit dense and said, “We—the United States.” I continued, “Does that mean you?” “No,” he replied. “The guys in the Army.” I then inquired if our boys should be put in harm’s way for interests that have nothing to do with the defense of the United States. If it is doing the “right thing,” he replied. “Are you willing to do what you call the right thing with your own body?” I asked. “Those guys are volunteers—they chose to do it. I’m just finishing my degree and have a good job lined up.” He is not a soldier and does not plan on becoming one—that is a job for someone else. In a republic, it is the job of the citizens; in an empire, it is the job of imperial forces.

Smedley Butler, who rose from lieutenant to major general in the Marine Corps and was twice decorated with the Medal of Honor, making him one of only two Marines in history to be so honored, concluded after 33 years in the Corps that

War is just a racket. . . . I believe in adequate defense at the coastline and nothing else. If a nation comes over here to fight, then we’ll fight. . . . I wouldn’t go to war again as I have done to protect some lousy investment of the bankers. There are only two things we should fight for. One is the defense of our homes and the other is the Bill of Rights. War for any other reason is simply a racket.

Semper fi, General Butler.

Leave a Reply