For most of the 19th century, the American West was a fairly tranquil place. The myths of Hollywood and the wishful thinking of certain revisionist historians notwithstanding, throughout the region, for every gunfighter there were a hundred stockbrokers, and for every outlaw, ten-thousand farmers. The West was urban as much as rural, settled as a joint venture of corporations and the federal government. (For more on that, see Richard White’s It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own, among other recent works of western history.) In cities such as Denver, Seattle, and even Tombstone, few citizens knew how to use a firearm, owned a gun, or had need to. The decades-long wars against the Native Americans were staged in remote corners of the country, far from the haunts of ordinary citizens, and, as for bad men, few but the local tall-tale spinner had ever seen one.

Lincoln County, New Mexico, was a notable exception. For three decades beginning in the 1860’s, the sparsely settled pocket of south-central New Mexico Territory saw more than its share of violence: regular raids on the part of the Mescalero Apaches and Indians from farther afield; crimes fanned by racial hatred between Anglos and Hispanics; bad blood between farmers and ranchers, ably documented in Conrad Richter’s novel The Sea of Grass; and a business rivalry that would lead to the so-called Lincoln County War.

Against this backdrop of bloodshed, many legends arose, but only one has endured: that of a young man named William Bonney, known in his time and ever after as Billy the Kid.

He was born between 1857 and 1860, probably in New York. (As befits a legend, the details of his birth are hazy.) The son of Irish immigrants who had fled the Potato Famine, his given name was—we think—Henry McCarty. In 1873, his widowed mother moved to Santa Fe, where she married another Irish settler, William Antrim, and her son took his stepfather’s name. The new family moved southwest to Silver City, hard by the Western Apaches’ mountain strongholds, hoping to find their fortunes in the mines.

Instead, William Antrim and his wife sickened and died, the victims of one of the many influenza epidemics that swept the world in the late 19th century. For the next year, the orphaned Henry skulked about Silver City, gambling, smoking, drinking, committing petty thefts. Within a year the bright, formerly well-behaved lad found himself in jail for having stolen a bushel of clothes from the town’s Chinese laundry. Rather than await trial, Henry Antrim, slender and short for his age, shinnied up a chimney that opened into his cell and disappeared into the night.

He made his way across the border into Arizona and sought honest work, finding it in the Sulphur Springs Valley laboring as a wrangler on the transplanted Texas cattleman Henry Hooker’s vast ranch. For a time, things seemed to be going well for “the Kid,” as the older cowboys called him. No one asked questions, and most looked the other way whenever he stole a saddle, a blanket, even a horse from Fort Grant, the nearby Army post. When soldiers eventually caught him in the act, he managed to escape northward to the gold and copper mines at Globe, Arizona. What Kid Antrim, as he sometimes called himself, did there is lost to history.

Two years later, he was back at the Hooker ranch, working as a cowboy. This time, he kept away from the Army post, but, all the same, he fell afoul of Francis Cahill, an ex-soldier living at the Hooker place. Nicknamed Windy for his explosive rages, Cahill took every opportunity to terrorize the youngster, slapping and insulting him. On August 17, 1877, Cahill hit the Kid one time too many, and the Kid struck back. Cahill drew his service revolver; they wrestled, and the gun went off in Cahill’s belly. He died the next day, but not before naming his assailant.

The Kid fled Arizona, and, in the autumn of 1877, a young man who called himself Sam H. Bonney arrived in Lincoln County. He could not have picked a worse time to come. In 1877, residents of the county faced frequent raids by the nearby Mescalero Apaches, who killed a cowboy or farmer from time to time and made off with cattle and horses. Hispanic campesinos, along with Anglos who married into Mexican families, had not only the Apaches to fear, but a local, murderous version of the Ku Klux Klan led by ex-Confederates. But these were small worries compared with the violence wrought by members of “the Ring,” a Santa Fe-based group of businessmen whose ranks included two of Lincoln’s most prosperous merchants, J.J. Dolan and L.G. Murphy, Irish immigrants locked in rivalry against John Chisum, the legendary rancher, for control of southern New Mexico’s cattle industry and all that came with it: banking, real estate, mercantile commerce, and the railroad.

Chisum’s closest ally in Lincoln was an Englishman named J.H. Tunstall, who had come to America with the goal of becoming rich before his 30th birthday. He was well on his way at 24, the owner of a working ranch, the Lincoln County Bank, and a dry-goods store that competed with L.G. Murphy & Co. Tunstall found a friend in Alexander A. McSween, a Scottish-born lawyer whom J.J. Dolan accused of embezzling funds. Briefly jailed, McSween made common cause with Chisum and Tunstall against the Ring. Tunstall made another friend when young Billy signed on with him as a ranch hand.

When he entered Tunstall’s employ, Bonney took on a new air of seriousness, working hard. Events would swiftly catch up with him, though. Back in Lincoln, the Dolan-Murphy and Tunstall-McSween factions filed one lawsuit after another—the one continuing to charge embezzlement, the other tax fraud. The Ring, in the meantime, bought the town’s sheriff, William Brady, who attacked Tunstall’s general store. Tunstall arrived in Lincoln with Billy Bonney to challenge Brady in court. At the same time, a sheriff’s posse went out to round up Tunstall’s cattle. The young Englishman ordered Billy to return to the ranch and await instructions.

The next day, Tunstall himself set out for his ranch. On the way, members of the posse, led by J.J. Dolan, ambushed and murdered him. Later mythmakers have him taking up arms at that very moment, but Billy Bonney first went to Lincoln Constable Atanacio Martinez and swore out a complaint against members of the posse. Martinez deputized Billy, and they went to serve Dolan’s arrest warrant at the Murphy & Co. store. When they arrived, Sheriff Brady, reinforced by soldiers from Fort Stanton, arrested the two. Martinez was released, but Billy Bonney spent the night in jail while, in another part of Lincoln, John Tunstall was buried.

On gaining his freedom, Billy Bonney joined with other Tunstall ranch hands in a ten-man vigilante force called the Regulators, led by an older man named Dick Brewer. They began hunting down members of the posse and killing them one by one, a vendetta that went on until midsummer and left dozens of men, including Sheriff Brady, dead. The governor of New Mexico Territory, James Axtell, outlawed the Regulators and ordered a new posse to go after them. On July 15, Billy and company returned to Lincoln and took up positions in McSween’s house along with the attorney himself, while Dolan’s gang laid siege for four days. On the fifth, they were joined by a small force from Fort Stanton, who brought along a Gatling gun and a howitzer. When McSween tried to surrender, he was cut down in a storm of bullets; Dolan’s men later set his body on fire. The next day, a Lincoln jury, doubtless aware of the Ring’s power, declared that he had died while resisting arrest.

Billy Bonney, now in command of the remaining Regulators, fled. The Dolan gang fanned out in pursuit, raping, pillaging, and murdering along the way, and blaming their crimes on the Kid. These were the worst days of the Lincoln County War, and they came so prominently to national attention that President Rutherford B. Hayes removed the hopelessly corrupt Axtell as governor and appointed in his place Gen. Lew Wallace, a Civil War hero whose novel Ben-Hur would be published a few months later. For more than a year, Wallace tried to convince Billy Bonney to give himself up so that he might testify in court against the Dolan-Murphy faction; their exchange of letters, with Wallace’s courtly prose and Billy’s simple declarations, marks what might have become a friendship under other circumstances.

When Billy was finally arrested in March 1879, however, he was not allowed to testify. Instead, he was charged with Sheriff Brady’s murder, which he did not commit. True to form, the Kid escaped. Not long thereafter, all charges against Dolan and his men were dropped. Now contemptuous of the law, Billy Bonney set out on the outlaw trail, rustling cattle and horses and selling them in Mexico. Strangely, the vast herd owned by John Chisum was one of the Kid’s earliest targets. Chisum retaliated by hiring a laborer named Joe Grant to assassinate the thief, but the Kid shot Grant instead, the second time he is known to have killed.

In the autumn of 1880, while the Kid drifted from one camp alongside the Pecos River to another, the citizens of Lincoln elected Pat Garrett sheriff. Garrett set out in pursuit of the Kid, and his posse soon had their turn at killing off Regulators one by one. Two days before Christmas, Garrett, who knew Billy casually, caught up with him at a small ranch called Stinking Springs and, after a brief gunfight, led him off in chains to Fort Sumner. His guards later transferred Bonney to jail in Santa Fe, from which he wrote to Governor Wallace to plead his case. Wallace was away on a trip to the East, and Billy’s letters went unanswered even after he returned.

By the spring of 1881, thanks to enterprising journalists, Billy Bonney was known nationally as Billy the Kid. (Larry McMurtry’s 1989 novel Anything for Billy does a fine job of pegging their role in the unfortunate young man’s rise to fame.) Readers across the country now followed the story as Bonney was led to a courtroom in the southern New Mexico town of Mesilla, found guilty of murdering Sheriff Brady, and sentenced to hang. On April 22, 1881, Billy the Kid was taken to Lincoln to await his execution. His jailers should have known by now that walls did not easily hold him. Six days later, he overpowered his guards, killing them both.

They were the last men to die at his hands. It is worth noting at this point that the number of dead who can be directly attributed to the Kid now stands at four, a far cry from the psychopathic tolls that legend would attach to his name. But then, Daniel Boone suffers the same problem: He complained late in his lifetime that he had killed only three men, and then in self-defense; Fess Parker usually knocked down at least that many Shawnee before the first commercial break of the long-running TV series that bore the great explorer’s name.

Pat Garrett tracked Billy down at the Fort Sumner home of Pedro Maxwell, a local rancher. Late on the evening of July 14, 1881, Garrett crept into the room where Bonney lay dozing. He must have made a noise, for the Kid sprang to his feet and called out “¿Quien es? ¿Quien es?”—bilingualism having been a useful skill on the border then and now, a phrase in the Spanish that he spoke so well, having been, after all, Catholic and Irish despite having been in English employ. Garrett replied to the inquiry by firing twice. One bullet struck the unarmed Bonney in the chest, and he died instantly. He was anywhere between 21 and 25 years old.

Henry McCarty. Henry Antrim. Billy Antrim. The Kid. Kid Antrim. Billy Bonney. Billy the Kid. How is it that this simple frontier boy, steered by fate into crimes far beyond his apparent inclinations, became the subject of so many legends? How is it that a man with fewer victims to his name than any one of dozens of criminals in the last few years became one of America’s most notorious outlaws? The myth, of course, is well served by the obscurity of his origins, by the shadows that fall between his real and imagined deeds.

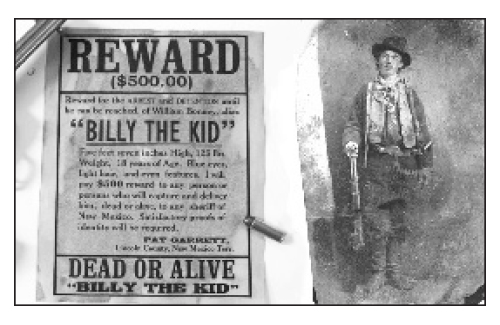

He was hardly cold in the ground before the first book about him, Thomas F. Daggett’s wildly imaginative Billy Le Roy: The Colorado Bandit appeared. In 1881 and 1882, another seven “yellow novels,” as pulp fiction was then called, would appear with some avatar of the Kid in the starring role. Most depicted him as a red-eyed murderer who had as many corpses to his credit as he had years—the highest count runs to 26 men, not counting Mexicans and Indians, who in those days were ranked on the lower rungs of the evolutionary ladder. Looking forward to a comfortable retirement, perhaps, Sheriff Pat Garrett produced his own memoir a year after he shot Bonney to death. Entitled Billy, the Kid: The Noted Desperado of the Southwest, Whose Deeds of Daring and Blood Made His Name a Terror in New Mexico, Arizona & Northern Mexico, it was substantially ghostwritten by Lincoln journalist Ash Upson. Garrett’s account lies at the foundation of the Billy the Kid myth, repeating stories that the authors surely knew to be untrue, inventing others to liven up the narrative.

Among the most enduring of the Garrett-Upson fabrications, perpetuated in dime-store Westerns ever since, is that the Kid killed his first man at the age of 12 for insulting his mother. Having launched that bit of fiction, the authors of Billy, the Kid have their protagonist gunning down one innocent soul after another for the pleasure of watching them die. More than one historian has suggested that Garrett and Upson gave Bonney a murderous reputation in order to make Garrett’s having shot the unarmed Kid (and earning a reward of $500) palatable to their readers. Alexander McSween’s widow, understandably biased, recalled years later that Garrett was well known for firing on his targets without warning. In any case, Garrett would be killed in 1908, a victim of a late iteration of that KKK band, well funded by a New Mexico senator, Albert Fall, who would be implicated in the Teapot Dome scandal in the 1920’s.

A Chicago journalist named Walter Noble Burns took Bonney’s legend on a new tack in 1926 with The Saga of Billy the Kid, repeating earlier inventions while giving his subject all the trappings of a folk hero, a Robin Hood for the coming Great Depression; Burns did much the same with Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, whose memories he revived at about the same time. Hollywood embraced the outlaw-as-hero myth with King Vidor’s 1930 film Billy the Kid, with John Mack Brown in the starring role. His wild-eyed portrayal established a model that most of the 40-odd films since made have repeated to some degree, among them Marlon Brando’s quirky rendering in One-Eyed Jacks (1961) and Michael J. Pollard’s maniacal performance in Dirty Little Billy (1972).

Oddly, the film that best captures the historical realities and complex politics of the Lincoln County War is the Brat Pack extravaganza Young Guns (1988). A smirking Emilio Estevez takes a sadistic pleasure in rubbing out his enemies that the documentary evidence simply will not admit, but otherwise, the screenwriters have most of their facts straight. Few critics noticed, or cared, but audiences flocked to the film—which suggests that when the next Western revival hits Hollywood, there ought to be room for another Billy the Kid flick that gets even closer to the real story without, of course, sacrificing the requisite gunplay.

We are left with an enigma. Barring the discovery of a secret cache of biographical data—Henry McCarty’s birth certificate, say, or an autobiography in his own hand—we probably know as much as we ever will about the curious career of Billy the Kid, a life far removed from the legend he inspired. Like so many who figure in the history of the American West, what stands before us is not a man but a myth. It will likely stand there, in the splayed-leg stance of a gunfighter, forever.

Leave a Reply