Lately, I’ve been studying a segment of German history about which I knew little as compared with the period before World War I or the great German cultural awakening between 1770 and 1820, sometimes characterized as die Goethezeit. Germany’s failure to stave off a Nazi takeover, which was well on its way to happening when Hitler became chancellor on Jan. 30, 1933, has been considered proof positive of a bad national character.

Supposedly, Germans were always following a “special path” toward a Nazi regime, which just took several centuries to reach its explosive end. This is the view currently propounded by German educators and the leaders of all German parties, except for the patriotic, right-of-center Alternative für Deutschland. But it may be argued that the Weimar Republic faced so many difficulties that it would have taken years of economic prosperity for the interwar German state to have won legitimacy in the eyes of the German people. Instead, it had to labor under the Depression that befell every Western country in the fall of 1929.

The Republic’s parliamentary organizers, who represented the Socialist, the Democratic, and the (Catholic) Center Parties, were compelled to sign a vindictive peace agreement inflicted on them by the victorious Allies. They were also, not incidentally, made to endorse this document under the threat of invasion without a prior right to negotiate. The defeated side had to pay an unspecified amount in reparations, swallow the loss of about a fifth of its territory, and accept a home defense force limited to 100,000 soldiers. Also, in Articles 227 through 232 of the Treaty of Versailles, they had to acknowledge “war guilt and sole responsibility” for all the human losses and property damage caused by the war.

The Weimar Republic also started out with French forces occupying the coal- and iron-producing Saar region, as well as a large chunk of the Rhineland, which the French vacated only in 1930. Germany’s former eastern borders barely existed after the war since most of what had been West Prussia and Silesia was given to France’s protégé, the newly established Polish Republic. Although Germans held on to a piece of East Prussia and at least indirectly the Free City of Danzig, which had a near majority German population, the Poles were left in a position to close off Danzig and to isolate East Prussia.

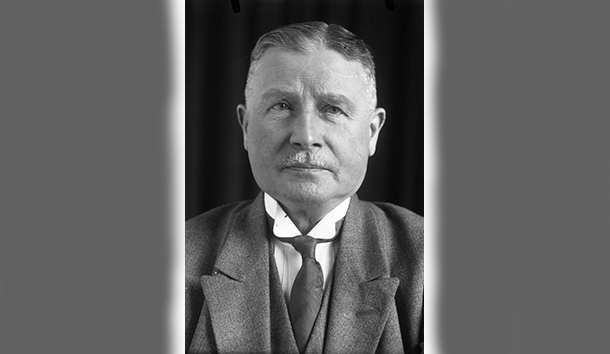

Given some of these political and geopolitical problems, and Germany’s perpetually feuding parliamentary parties, it is a wonder that the Weimar Republic survived for as long as it did. That this was possible was owing to the dedicated, patriotic statesmen who served the “German fatherland.” Several of these stand out as especially commendable political leaders: the first president of the Republic, Friedrich Ebert; a later chancellor and foreign minister, Gustav Stresemann; the minister of defense and later minister of the interior, Wilhelm Groener; and the chancellor between 1930 and 1932, Heinrich Brüning. All but the Republic’s first president, Ebert, who was a moderate socialist, were by disposition monarchists who rallied to the post-war regime as Vernunftrepublikaner, or sensible rather than sentimental republicans.

The last kaiser, Wilhelm II, had in any case become useless to his country once he had been talked into abdicating and obligingly went into exile on Nov. 9, 1918, at the urging of Groener, who was then a member of the German High Command. The kaiser took this fateful step principally to please the American president, Woodrow Wilson, who refused to negotiate with the defeated Germans unless they first unseated their ruler. The French, who pushed for the hardest peace against their German rivals, seem to have been utterly indifferent as to which head of the German government they would inflict their terms on. But once the kaiser had left to take up residence in Holland, not even the explicitly monarchist German National People’s Party (DNVP) did much to bring him back. The German war commander, Paul von Hindenburg, who became the Republic’s president in 1925 and was then reelected in 1932 in an election against Hitler, was known as a staunch monarchist. But not even this venerable Prussian officer, who had led the Kaiser’s forces during the war, seemed concerned about a monarchical restoration.

In Alternativen zu Hitler: Wilhelm Groener (2008) Klaus Hornung, a onetime professor of political science at the University of Hohenheim in Stuttgart, puts into relief Groener’s struggle as a military officer and minister to preserve the Weimar Republic. Although a member of the German High Command who enjoyed exemplary relations with his superior, Hindenburg, Groener became known for his political flexibility. At the war’s end he developed close ties to Friedrich Ebert, upon whose cooperation he depended to put down radical leftist uprisings after the War. The majority socialists, the Mehrheitssozialisten, backed Ebert and his defense minister Gustav Noske, despite defections on the Socialist Party’s left, in dealing with what Ebert as well as Groener condemned as a violent threat to Germany’s constitutional republic. Later in the 1920s as defense minister, and from 1931 to 1932 as interior minister, Groener tried to cooperate with the democratic left in building a workable parliamentary coalition that would exclude both the Nazis and Communists.

In the German election of September 1930, which came at the height of the Great Depression, the Nazis and Communists together won enough seats in the Reichstag to create a near obstructionist majority, a Sperrmehrheit. The Nazi deputies in Germany’s parliament shot up from 12 to 110, although the chancellor at the time, Heinrich Brüning of the Center Party, commented in his Memoirs that he expected an even more resounding victory for Hitler’s party.

Groener made multiple enemies on the German nationalist right, for understandable reasons. He talked the kaiser into abdicating, then induced parliamentary leaders to sign the Treaty of Versailles, including its “shame paragraphs” blaming Germany for the war. Although Groener considered the treaty to be outrageously unjust, he also believed Germany’s armed forces were in no condition to resist an Allied invasion if one were undertaken. Later as interior minister he persuaded Hindenburg to ban Nazi paramilitary groups, and in his persistent effort to place the Reichswehr “above parties,” Groener prosecuted young soldiers who distributed inflammatory Nazi literature in their barracks.

In the summer of 1930 Hindenburg established “a presidential regime” under Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution, which allowed the aged executive to govern “under emergency powers.” Groener supported this move as necessary to protect Germany’s republic and, with Brüning, became a leading figure of the “emergency cabinet.” Like Hindenburg, Groener and Brüning were convinced that this assertion of constitutionally guaranteed presidential power was necessary to save their country from the Nazi and Communist dangers.

During Groener’s political service to the Weimar Republic, he tried persistently to win over American Republican administrations. Wishing to free his country from onerous reparations and to rebuild the German army, he recognized that American leaders had no interest in further humiliating the Germans or keeping them in an economically weak position. By the 1920s, moreover, second thoughts had set in across the ocean about America’s involvement in World War I, and certainly about the harshness of the Treaty of Versailles. Both Groener and Brüning thought they could link plans for disarmament among the major powers to Germany’s own interests.

If Germany’s former enemies cut their military expenses and reduced the sizes of their armies, the resulting situation might lead to a revision of the status quo for the war’s losers. The Germans might then have been allowed to achieve military parity and have their reparations costs shrunk. But this would not happen. The British and French were unwilling to accept a revision of the Versailles Treaty that would have permitted the Germans to create a serious military force. Additionally, the Depression put the French in a financially precarious position, rendering them more dependent on German reparations. Note that much of the money paid in reparations came from American banks, which provided the Germans and other Europeans with generous loans.

Groener lost his cabinet posts in June 1932, at which point his former assistant, Gen. Kurt Schleicher, formed a new government with the devious Center Party politician Franz von Papen. This successor cabinet moved toward the position of allowing Hitler into the government, supposedly on the government’s own terms, a move that Groener and Brüning doggedly resisted. By 1932 Hindenburg had become a decrepit shadow of his former self, and he was finally persuaded to bring the Nazis to power by his son Oskar, whose financial irregularities enabled Hitler’s henchmen to blackmail him. In 1934 Hitler rewarded Schleicher’s assistance by having him murdered during the Night of the Long Knives. Von Papen barely escaped this bloodbath, which was carried out by the Brownshirts against Hitler’s internal targets.

Perhaps because of both his moral stature and his retirement from political life, Groener was left untouched. In 1933 this forcibly retired statesman pointed out the obvious: As late as May 1932 it was possible to work with an anti-Nazi coalition in the Reichtstag. And, while the fall of Brüning’s government had actually resulted in a crisis that added to the Nazis’ electoral strength, it had begun to ebb by the end of 1932. Further, if Hindenburg had not agreed to make Hitler chancellor when he did, the Nazis’ appeal, which correlated with the intensity of the Depression, would have declined by 1934, when an economic upswing occurred.

A naïve observer might think that the German Federal Republic would be celebrating Groener as an anti-Nazi warrior allied to the moderate socialists. Guess again! The only reason that Hornung’s matter-of-fact biography was published at all is that a very conservative Austrian press, Leopold Stocker Verlag, agreed to do so.

By current German antifascist standards, Groener was a highly suspect figure. He opposed a radical leftist revolutionary takeover of Germany in 1919—a revolution which would have been a good thing according to the current German intelligentsia. And, behind the backs of Germany’s “democratic” enemies, he built up the Reichswehr above the 100,000 limit stipulated by the Treaty of Versailles. Groener was also an avowed German patriot, who did not express the now obligatory loathing for his country that characterizes today’s successful German politicians and intellectuals.

Oh, and lest we forget: He coordinated Germany’s military transportation system in World War I and failed to defect to the other side. Recently the city of Dresden fired a bus driver for daring to write in German that he was a “German driver,” presumably to indicate that unlike other drivers he could speak to passengers auf Deutsch. It’s highly unlikely this would have befallen a Muslim immigrant bus driver who chose to advertise his non-German nationality.

Image Credit: Wilhelm Groener c. 1928-1932

Leave a Reply