The epidemic of AIDS highlights a crisis in policy on which the social sciences may shed some light. In the process, it may also move the study of policymaking to some substantial higher ground. Whenever we pose a question in terms of understanding rather than resolving, we run the risk of hearing social research denounced as irrelevant, if not downright obstructionist. Yet such a risk is minor compared to a bland acceptance of a presumed common wisdom that often points to an uncommon folly. With AIDS, for example, a recitation of raw numbers of potential victims is of less importance for policy than the demographic, geographic, and sexual characteristics of those involved.

We need to begin, then, by a disaggregation of macropolicy from micro-policy. In one sense, the former is a bundle of issues composed of the latter. But each has dynamics of its own. Affirmative action is a macro-policy. But it is derived in part from Executive Order No. 11246 issued during the Lyndon B. Johnson White House years. In its specifics, this order concerned government hiring. Now mandated quotas have been imposed on ever wider areas of both the public and private sector. At such a level, the concept of policy is a 20th-century equivalent to the 19th-century notion of geist or espirit. Racial equity is not so much a crafted political position as a broadly felt need of the age. It exists across class no less than racial boundaries.

The issue of developing a policy toward AIDS is something else again. It is a specific disease which afflicts a special segment of society, for the most part urban homosexual communities, and to a far lesser degree those who use drugs or have had blood transfusions. Further, it is an area in which a general policy consensus does not currently exist, and hence, the capacity to impose a policy on a society is more readily strained. Finally, it is an area in which neither the scientific nor medical parameters are entirely understood. For example, the length of the incubation period varies greatly, and only recently has it been publicized that AlDS tests may fail to indicate the infection for more than one year. Hence we can look at the AIDS problem as a relatively “pure” case of the extent to which policy is effective in contexts of both scientific doubt and intense social polarization.

The policy differences between those who, like Education Secretary William J. Bennett, advocate avoiding premarital sex and illegal drugs as the most virtuous, safest, and smartest way to prevent AIDS infection and those who, like Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, emphasize prophylactic and public health measures to reduce the risks among the sexually active, are indicative of a general crisis in policy as such. In the intensifying debate between the abstentionists and pragmatists, and a corresponding confusion over normative frameworks of behavior, description rather than prescription may well prove to be the order of the day.

That, at any rate, is what Hiatt and Essex (1987) claim when they urge politicians to clarify their policy persuasions on such issues as: (I) conflicts between public health requirements and the homosexuals’ rights to privacy; (2) who should pay for treatment; (3) what ancillary programs should be introduced for drug users; (4) what should be done to prevent AIDS in the newborn; (5) how research can be encouraged; (6) what educational programs should be advocated; (7) how international cooperation can be fostered in AIDS research and prevention; (8) how fiscal priorities would be set, and at the expense of which current programs.

Before such a leap into policy considerations is made, it is important to state a few social truths about AIDS. It is precisely these that are dangerously obscured by phrases like “alternative life-styles” (as opposed to “safe life-styles”) and “high risk groups,” in contrast with specific mentions of homosexual populations, as well as the “homophobic bias,” when the issue of victims is broached in a concrete fashion. This avoidance of the brute fact that nine out of 10 victims of AIDS are homosexuals (the figure would be even higher if the so-called bisexuals were included) is typical of people who want clear-cut policies even as they move to obscure clear-cut evidence.

At present no AIDS vaccine is available and no satisfactory antiviral drug exists. The widely used azidothymidine, or AZT, is so toxic that roughly 50 percent of AIDS patients cannot take it. We also know little about the origins of AIDS. It seems that the disease exists in a benign fashion in the green monkey of Africa, but that it becomes virulent in humans. AIDS can incubate for a great period of time, can be transmitted from the female no less than the male, and is infectious in carriers for years without the victims’ knowledge. As a further complication, testing for AIDS is not allowed, and on those rare instances when it is, it is not always possible to identify specific individuals as carriers. Thus, generating policies for AIDS is at best a vague and general activity, which comes hard against the granite wall of constitutional law, no less than it does against medical and chemical inadequacies.

What we see instead is the development of long-term policies based on demands for increased funding for AIDS research in order to bypass or avoid dealing with short-term realities. The policy of treating AIDS has turned into a metaphysical disposition to develop a way to disregard social consensus, limit the scientific information base, and confuse moral premises. A good example of this is the manipulation of the AIDS epidemic by groups like the Planned Parenthood Federation of America to foster the need for a “nationwide sexuality education,” with little, if any, commentary on the actual problem of the plague (AIDS) as such. Given the nature of special interest groups in America, this sort of tendentious spin-off approach may be expected to become common currency among all sorts of secular and religious groups, on all sides of the issue.

Whenever a serious problem emerges in American society, the call for public action is sure to follow. One inevitable consequence of this is the formation of a presidential commission. And as we can see, this has already taken place, with the attendant bickering over the composition of the commission consuming most of the time and energy of the trouble-shooting body. At a more proximate level, a somewhat typical plea to “do something” was registered in an issue of The New Republic, which boldly presented “Our Cure for AIDS.” Arguing that in a response similar to Father Paneloux’s at the outbreak of The Plague, all neutrality is culpable, judgment a form of withdrawal, while only action becomes a moral necessity. So the first step toward a policy is a calibration of the moral trade-offs (i.e., private rights versus public goods), with everything else logically ensuing from there.

Martin Peretz then moves from the general to the specific rapidly: (a) public educational campaigns that are “explicit, colloquial, and geared less to restrictions on sexual pleasure than to guidelines for the possibility of safe, and enjoyable sex”; (b) the dispensing of condoms and their placement “in all bars and clubs” including “handing out condoms at the exit door of any club charging admission after 9:00 p.m. and at all rock concerts”; (c) reaching the neediest (i.e., blacks, Hispanics, and the poor, the fastest growing group of AIDS victims), which would include dispensing and providing clean needles to drug addicts on demand.

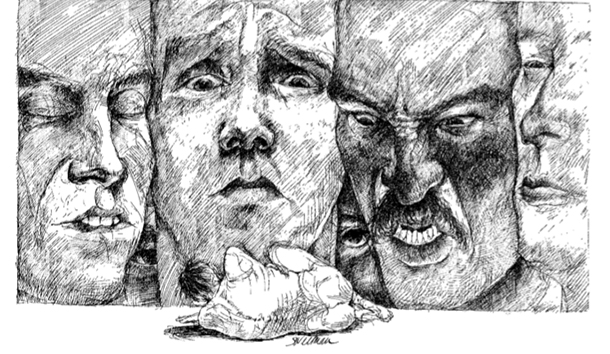

At the conservative end of the spectrum, the concerns are less with a policy to protect the victims of AIDS than to safeguard the innocents from exposure to the AIDS victims or carriers. It might be said, therefore, that these are demands for antipolicy, i.e., the cauterization and isolation of AIDS victims from the general society. To be sure, when efforts are made to foist the AIDS victims or their children on the general population, the revulsion is as violent as it is complete. Fire-bombings, school boycotts, withdrawal of insurance premiums are now random, sporadic but also frequent.

The philosophical foundations of such an antipolicy position are set forth by Adam Meyerson in the journal which he edits, Policy Review. It is his view that “with the AIDS scare and the death of prominent athletes and actors from cocaine. Nature has been confirming conventional morality by showing that there are certain things the human body is not supposed to do.” It is clear that the use of the word “Nature” is precisely equivalent to the word “God.” And if nature or God carry demonstrable proscriptions on action, then clearly, policies intended to reverse such patterns can only be viewed as antinatural or worse, blasphemous.

A serious problem with the pure conservative approach is that even if a laissez-faire environment were desired, in which the victims of AIDS would self-destruct, the nature of disease would still demand a policy to protect the general population. Society still needs a set of policies on how to quarantine the victims, how to tell the victims from nonvictims (i.e., medical clearance and surveillance of the population as a whole), with forms of indemnification for the victims as well as types of punishment for carriers who spread the disease knowingly. Only the most parochial view of policy would equate “doing something” with providing additional funds for medical research.

This is only a brief overview of the extremes of policy responses to AIDS, which does not remotely exhaust our approaches. The options between these two poles are numerous and are largely put forth by serious people. But our concerns here should be less the issue of AIDS than the problems which constantly, consecutively, and unpredictably beset the world of public policy. Indeed, it might be wiser to speak of the many worlds of public policy, since on an issue like AIDS, policy involves legislative supports, executive orders, judicial decisions, voluntary actions, and/or local agency funds. For, built into the structure of policy, invariably subjecting specific recommendations to criticism and correction, is the multiplicity of levels of effort aimed at addressing a single specific problem. What can social science contribute to this environment in which dissension rather than consensus prevails, and in which good and honest people come to resolute and seemingly contradictory conclusions. For on a subject like AIDS, though there is broad agreement on the existence of widening contagion, what is missing is consensus on what, if anything, anyone should do to limit or overcome the problem.

Richard Berk, in a recent provocative article in the American Sociologist, notes that there are currently no experts on the long-range social consequences of AIDS. He proposes that social research produce experts, develop a crash program in social projections, and come up with the tools for such projections, all in short order, given the acceleration of the AIDS epidemic; and finally, achieve all this in the context of big science (i.e., many researchers from different fields working with large budgets, or at least with minimal fiscal constraints).

This would entail subjecting all efforts at policy to empirical scrutiny—that is, examining the scientific, political, and moral obstacles to new policy. Again, what follows by no means exhausts the information available. But it does present a way of handling policy beyond the pure optimism of expecting to change existential reality and the equally undiluted pessimism in which prudence and natural laws are wielded like clubs.

Since so much has been made of preventive medicine, at least during an interim in which “cures” are simply unavailable (if indeed attainable at all), it is fair to limit our concern to the impact of condoms on the AIDS population. While there is little doubt about the prophylactic properties of condoms, and their capacity to reduce the spread of AIDS within homosexual populations, especially when used together with spermicides, serious questions remain.

Among the concerns raised are the following: (1) among the sample batches tested, the Food and Drug Administration found that 20 percent of the latex condoms failed water leakage tests. This failure of 41 of 204 batches exceeded agency standards; (2) the failure rate for imported condoms is significantly higher than for domestic brands; (3) latex condoms are less subject to microscopic damage than natural condoms made of lambs’ intestines. Further, beyond the character of contraceptive devices are the human elements: (4) anal intercourse is far more traumatic than vaginal intercourse, hence the wear and tear on condoms is much higher; (5) the potential for transmitting AIDS is higher than pregnancy rates because women are fertile only a few days each month, whereas the AIDS virus apparently can be spread all the time.

Scientific studies of the effects of condom use in AIDS prevention are rare, given the ethical questions about establishing control groups in experimental situations. But in one survey of AIDS patients and their uninfected heterosexual partners, it was found that two of 12 who claimed to regularly use condoms became infected with AIDS. Without doubting the prophylactic values of condoms, therefore, the belief that a macro-policy can be built upon condoms is obviously dubious. Beyond all such concerns is the problem that the very belief in condom effectiveness may actually increase homosexual activity, and thus partially offset the very prophylactic values currently being relied upon.

Rather than speak of political processes in general, for present purposes it might be best simply to restrict our discussion to public opinion surveys. The making of policy under dissensus is far more troublesome than under consensual conditions. And while 78 percent of Americans said that AIDS sufferers should be treated with compassion, once the Gallup poll became more precisely worded, the actual gap in sentiment was seen as quite substantial.

While 48 percent of those polled said AIDS victims should be allowed to live in the community unimpeded, 29 percent disagreed. On the issue of jobs, 33 percent said that employers should be permitted to dismiss those infected with the AIDS virus, while 43 percent said that they should not. And on the question of responsibility, the public view is that 45 percent agreed that most people with AIDS have only themselves to blame, while only 13 percent disagreed. And on the crucial statement “I sometimes think that AIDS is a punishment for the decline in moral standards,” 42 percent agreed with this proposition, while 43 percent disagreed, saying they did not hold that view.

At the other end of the political spectrum are the powerful forces mobilized in select urban centers by the homosexual community, for whom everything from closing bathhouses to testing and identifying AIDS victims is anathema. Although estimates indicate that in a city like San Francisco there are perhaps 75,000 homosexual men, or 10 percent of the city’s population, and although half of them may be infected with AIDS, the threat has not been translated into specific policy recommendations. Local ordinances prevent San Franciscans with AIDS from being fired from their jobs. Nor can they be denied housing or evicted because of AIDS diagnosis. Insurance companies are not allowed access to results of the AIDS antibody test in assessing insurance premiums. In a city like San Francisco, it is taboo to criticize homosexuality however obliquely, without being condemned as a bigot. Few politicians dare not support “gay pride,” much less advocate sexual abstinence. Hence, while a consensus does not exist at a macro-political level, micro-political considerations further inhibit even timid articulation of policy.

This public opinion division thereby moves the issue of AIDS to a moral center of gravity. But ethical parameters are hardly self-evident. The utilitarian argument that self-interest is all-determining comes hard upon those who argue that social interest must prevail. Further, self-interest can be defined in terms of serving others as well as self. Ethical slogans about the “greatest good for the greatest number” may rend the fabric of a system predicated on “no exploitation of a disadvantaged minority for the benefit of an advantaged majority.” The right to know comes hard upon the right to privacy. Compassion comes upon retribution in arguments concerning capital punishment. The right to life comes upon the private right to determine capabilities of support.

It is far simpler to discuss ethical concerns in terms of good versus evil, truth versus error, or truthfulness versus lying. But these are less ethical dilemmas than moral imperatives, derived from the Western religious culture. And it is precisely the invocation of that culture which is used by those who argue against an AIDS policy per se. In a world of ethics, the choice lies between principles that can claim a wide number of adherents, in a world of alternative goods. In this sense, achieving a balance between pressures for reform (policies), and compliance with long-standing standards (ethics) is dramatically highlighted by the AIDS epidemic.

One illustration may suffice: A majority of the population favors the quarantine of AIDS victims. While this same public does not accept the quarantining of people because of their sexual preferences, they do hold that the risks to the uncontaminated public warrant such severe measures. But of course to adopt such a policy is to deny basic civil liberties and personal rights to a special segment of the American population. It raises also the specter of extending similar measures to other sectors of the population. There is a long gap between an individual with AIDS and a cluster of AIDS victims presenting a community threat. Hence, we see the stark contradictions between public policy and public morality in the emergence of AIDS as a national problem.

Moral discourse in the United States tends to be framed in terms of interest, purpose, and preference—that is, structurally. But phenomena like the AIDS epidemic are likely to refocus our understanding of public morality in at least two respects: One, they will shift the center of gravity from moral codes to moral decision-making and the policies thus entailed. The appeals to normative structures are only one aspect of moral coding. The other is reformulating the processes by which moral behavior gets defined. And this is a consequence of policymaking in issues like AIDS.

What we have, then, is a clear distinction between the development of social science and the manufacture of public policy. This distinction does not imply a contradiction between the two, but that the realms of discourse are distinct and that social science cannot simply be invoked in the name of policy. In short-run terms, wide condom disbursement would probably help contain an AIDS epidemic that threatens to kill more people than any disease except heart attacks and cancer. At the same time, the cultural imperative upholding such a short-term policy maintains that homosexuality is a legitimate alternative life-style, the criticism of which is homophobic or just plain neurotic (in direct contrast to earlier psychoanalytical traditions, in which homosexuality was held to be a neurotic affliction).

The attitudes toward heart disease and acquired immune deficiency syndrome are radically different. There is no vociferous demand for building massive numbers of Jarvik:7 artificial heart units. Rather, the call is for change in personal life-style: abstinence, no smoking, cutting down on the intake of caffeine and carbohydrates, less stressful modes of life. But in the case of AIDS, calls for abstinence are mostly met with derision and contempt. What we are faced here with, then, is the power of a social movement, rather than the worthiness or worthlessness of public policy.

Thus we come upon the limits of policy rather than the simple disenthrallment with policy. The cry to do something boils down to individuals doing something (i.e., as in the case of heart patients being urged to desist from smoking cigarettes), as opposed to the cry that the society do something, as in the case of AIDS patients who are urged to demand social supports that would not entail a change in personal behavior. The current thrust, the impulse, of policy is most often for governments to correct imbalances among populations; but in the case of AIDS, in the absence of consensus at least the issue of policies designed to eliminate a specific contagion or illness should be treated within a larger context of scientific, political, and moral considerations. That panoply of concerns is what the social scientific study of public policy is about.

There is a specific lesson in all of this for those whose chief concerns are the scientific study and practical implementation of public policy. To be successful, policymaking needs either of the two requirements: a broad-based public consensus on issues under consideration or a narrow-based elite consensus on issues about which the general public is either unconcerned or incapable of being intelligently informed.

Where there is a wide dissensus and equally broadranging discussion, there policymaking becomes extremely difficult and is often reduced to piecemeal or ad hoc considerations. The limits of policymaking, therefore, can be seen quite clearly in the controversy over what should be done about AIDS. For the moment, and many moments to come, there is very little agreement on the need for exact information, hardly any consensus on the implications of the medical aspects of AIDS, and virtually no agreement on the moral basis of public behavior. When and if such a set of agreements is forthcoming (as is perhaps more likely in the matter of AIDS) and the medical aspects of the problem overwhelm common ideological proclivities, then policies will become possible. In the meantime, the demand for policy serves to acerbate rather than alleviate partisan considerations.

In his recent introduction to The Art and Craft of Policy Analysis, Aaron Wildavsky notes that under what he calls “elite polarization,” policy analysis should become chastened and attempt to move from a one-sided emphasis on policymaking to a search for the source of preferences and movements. Such a salutary sociology of knowledge approach is heartily to be endorsed and should be urged to move even further, to indicate that under conditions of mass polarization the potential for even this limited achievement may be hard to establish. At the moment, wisdom dictates that AIDS public policy has been preempted by the need for social and behavioral science. This is perhaps another way of saying that knowledge should be a guide for action, but in the absence of any consensus on the truth about an illness, demands for policy or action become as dangerous, if not more so, than assertions or admissions of learned ignorance.

Our age tends to insist upon firm linkages between descriptive and prescriptive patterns of behavior. And while this may be admirable, we must not lose sight that there is a causal disjunction between the two. Accurate description must precede prescription, if we are not to fall prey to the sort of fanaticisms and myth-making scientists often accuse others of basing their actions upon. It is this tentativeness at the empirical level, no less than dissensus at the ethical level, that should serve as a limit to those who would leap to policy recommendations without delay. If the wish is father to the act, then too we should recognize that the fact is mother to the wish. Such homiletics may not lead us to instant solutions for such dread diseases as AIDS, but at least they will hold in check any approach that can only create more insoluble problems by demands for immediate, and more perfect policies.

Leave a Reply