In 525 A.D. the Lady Philosophy reminded Boethius, in his death-cell, that true philosophers must think body, rank, and estate of less importance than their understanding of what was truly their own. This understanding of philosophy, which is also Epictetus’s and Aurelius’s, as something more than a pleasant enough word game, has been neglected by modern sophists, though “taking one’s troubles philosophically” is still a common enough phrase. Those ancients who, not being Socrates, still thought they ought to want to be Socrates, thought of the Hebrews as a nation of philosophers, not because they asked questions, or practiced a careful casuistry, but because they served God, because they saw our ordinary “waking” world as fragmentary or dreamlike by comparison with reality.

If moderns discuss the thought that our present life is a dream, it is as a problem in epistemology to be neutralized—like other great problems—by suggesting that it is somehow impossible to question the fundamental framework within which we live. A better understanding of that thought is as an ethical one: are we right to assume that things are as they appear to us, under the influence of desire or fear or self-esteem? The ancient answer, still worth considering, is that they are not, that this life is, in Marcus Aurelius’s words, “a dream and a delirium,” that we do not see things straight until we see with the eyes of Reason.

The moral dangers of thinking this life but a dream are not so great: Epictetus believed that we began to wake up precisely through our recognition of moral duty. The thought was not intended to deaden but to increase our moral seriousness. If the real world is not what the “true philosophers” thought, we have no good ground to think that wisdom is worth pursuing, or even attainable. If we take philosophy—or science in general—with proper seriousness, we must try to wake up and remember who and what we are, and what is ours. Remembering that, we can begin to glimpse, “as through a narrow crack,” what the Lady Philosophy intended.

Sophists and Sages

Even today philosophical texts, at least in public libraries, are usually found next to the volumes of moral or spiritual uplift, but few people would find it natural to turn to modern analytical philosophy as consolation for their troubles, as they might pick up a book of crossword puzzles, or the latest thriller. People may still imagine that philosophy is “what you need in times of trouble,” or that it offers the appearance of occult or esoteric knowledge. Once they find out what modern philosophers actually do, they are rapidly disillusioned.

It is perhaps no bad thing, of course, that university lecturers have fewer pretensions than the “wise men” whom Socrates interrogated. We are paid to teach those who wish to have a university qualification, and to write books and articles on selected texts and topics. We are not paid to prepare ourselves, our pupils, and our readers for disgrace and death, to stand out against unjust rulers, nor even to practice more than the bare minimum of civil virtue. Teachers of philosophy, as we now understand the phrase, are not expected to philosophize, to prefer wisdom, truth, and integrity to their professional advancement, the applause of their peers or of the public, or their health, wealth, and security. Perhaps some do, but I doubt if many can read Epictetus’s rebuke (suitably modernized) without a qualm: “don’t be childish: now a philosopher, then a tax-inspector, then an advertising executive, then a Parliamentarian.” Don’t think of philosophizing as a temporary occupation, or an easy one.

It’s for this that the young men leave their fatherlands and their own parents? To come and listen to you interpreting trifling phrases? Ought they not to be, when they return home, forebearing, ready to help one another, tranquil, with a mind at peace, possessed of some such provision for the journey of life, that starting out with it they will be able to bear well whatever happens, and to derive honour from it? And where did you get the ability to impart to them these things which you do not possess yourself?

The lessons that philosophers ought to rehearse, to write down daily and to put into practice, are the primacy of individual moral choice, the relative unimportance of body, rank, and estate, and knowledge of what is truly their own and what is permitted them. Philosophy is the care of the soul, and anyone who pretends to “teach philosophy,” so Epictetus advises us, without the knowledge, virtue, and strength to cope with distressed and corrupted souls, “and above all the counsel of God advising him to occupy this office,” is a vulgarizer of the Mysteries, or a quack doctor. True philosophers must expect their attentions to have a real, and perhaps a painful, effect. A rough cloak and long hair—or as we might say, a university post—do not make the philosopher.

Sophists like myself may find the old puzzles entertaining, and may take pleasure in teasing the naive with arguments for the impossibility of knowledge, of change, of individual consciousness. But our professional efforts are usually directed at immunizing ourselves and our pupils against any threat to a comfortable conventionalism. We are professionals, it is possible cynically to think, because we are immune or indifferent to the texts we study. Those who take the infection drop out from the life of honor and applause to become monks or missionaries or road-sweepers. That Plato or Parmenides, Berkeley or Bradley, Hume or Heidegger might actually have been correct, even if occasionally sophistical, is not a thought to take too seriously. True, there are professionals who manage to combine analytical rigor (which is no bad thing) and philosophical courage, but the times are against them. Professional philosophy is Penelope—constantly unweaving by night the web of propositions she had woven by day. What is it about philosophizing that makes it worth our notice if it really contributes nothing to the well-being of philosopher and audience except a brief amusement? What makes it worthwhile if it does not even do that, but instead engenders a severe depression or confusion (as it demonstrably sometimes does)? Pursuing an occupation that leads merely to depression is surely perverse, though philosophers are not the only ones to do it (think of literary critics, political commentators, Freudian psychoanalysts. . . . ).

Ancient philosophy was not merely analytical enquiry. Ancient commentators sometimes called the Hebrews a nation of philosophers, but not because Jews are always asking questions, as the Skeptics do (“Why does a Jew always answer a question with a question?” “And why shouldn’t a Jew always answer a question with a question?”). The Hebrews were philosophers because (it was supposed) they worshipped an invisible god and dedicated all their lives to virtue. Greek commentators did tend to downgrade or ignore those aspects of Mosaic Law that struck them as vulgar or irrational, just as they tended to ignore Brahminical doctrine that did not fit well with their picture of the Hindu sannyasin as a “gymnosophist,” a naked philosopher. Such practices, of course, could be interpreted as outward and visible signs of an inner discipline (as the cloak and long hair favored by pagan philosophers should be). Epictetus confesses that he and his disciples are, as it were, Jews in word but not in deed: parabaptistai, not dyed-in-the-wool, very far from applying the principles they preach: “so although we are unable even to fulfill the profession of man, we take on the additional profession of the philosopher.”

The philosopher’s advice is not, as I have myself sometimes mistakenly suggested, to view such externals as indifferent, to cut emotional and social ties and think only of one’s own security (and what is that once I have lost all interest in the world?). It is to remember what and where we are, and not to be a slave. And slaves among slaves we shall be, until we are ready to die by torture, if it is our job. Our duties are generally measured by our social ties, by our role in God’s drama, not by our immediate likings or our wish to hang on hard to what is lent to us. First, we ought to remind ourselves first that all earthly matters occupy a mathematical point in comparison to the width and duration of the cosmos; and second, that anger, greed, and ignorance conceal even such reality as we can see. Things as they first present themselves are tainted with our hopes and fears; they are seen as instruments for, or obstacles to, our worldly purposes. It is the nonpossessive welcoming of what is real, what Jonathan Edwards called “the cordial consent of beings to Being in general,” that philosophy once practiced. As I wrote some years ago, “the effort to rediscover equanimity when in a bad temper, and the effort to uncover truth when at the mercy of social prejudice, are very similar. Both seem to involve a putting of oneself at the disposal of the universe . . . Being thankful for things as they are, praying for one’s supposed enemies as they are, rejoicing in the sense of being a unit in a wider and happier whole—these are ways in which we can escape despair.”

Waking Identities

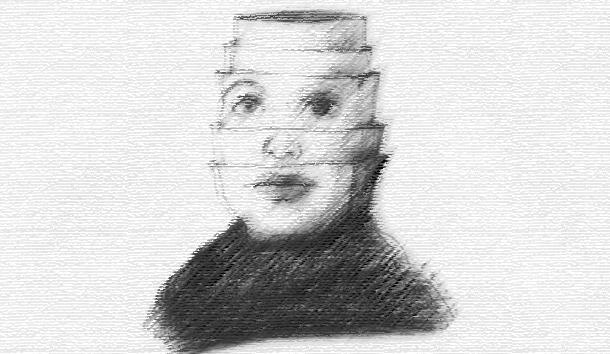

And what is this thing called “I” that must not be identified with worldly wishes, wealth, or reputation? The more softly a captive lion lives the more slavishly he lives. Epictetus imagines how a captive bird might speak: “my nature is to fly where I please, to live in the open air, to sing when I please. You rob me of all this and then ask what is wrong with me?” Vine and cock alike do ill when they go against their nature; so also man, whose nature is not to bite, kick, imprison, or behead but to do good, to work together, to pray for the success of others. The greedy, disputatious, tricksy, angry, timorous, slothful, fickle, or lustful cannot properly be considered human, but have the spirits of animals—or those spirits that the ancients (and more modern thinkers) regularly reckoned animals to have. What we are, by nature, is not what now appears: “[we] have a little forgotten [our] real self,” being clouded by a mist of mortal affairs that the Lady Philosophy shall wipe away. Because our nature is to be aware of what we can be, we can conceive the negation of that self-awareness, and forget. In a Platonic world one’s nature is not what now one usually does, but what the eye of reason can discover we should do, if not perverted from the old straight way.

Remember that you are an actor in a play, the character

of which is determined by the playwright. If He wishes

you to play the part of a beggar, remember to act even

this part adroitly; and so if your role be that of a

cripple, an official, or a layman. For this is your

business, to play admirably the role assigned to you;

but the selection of that role is another’s.

Not body, nor rank, nor estate, nor reputation is me: those are all things I put on, and may be diverted by. My being is only known in my recognition of duty. What is the self-knowledge the philosophers require, and what is the self that is known? Modern existentialists, perverting an ancient doctrine, have decreed that the human self is a vacuity, that we have no real nature, no duties prior to our own, entirely arbitrary, choice. Modern naturalists, no less despairingly though with more consistency, have held that what we are is simply discoverable: we are animals whose nature is dictated by our evolutionary past. Both sides have taken the present world for granted, and they differ only by the extent to which they think self-knowledge is absurd. I shall pick up the hint that both unconsciously give us in a moment: what we know of ourselves, the self as object of our cognition, arises within a wider, unknown self. What we are is not the thing we think.

A full investigation of these mysteries, to state the obvious, is far beyond my ability. What I shall be considering in this second section is the simple thought, much mocked by moderns, that this life’s “a dream and a delirium” (as Aurelius said). Epictetus is wary of saying that we cannot distinguish waking life and dream, but it is an error to suppose that he is making the merely bourgeois claim that our present, ordinary life is wakeful. A feeble or frivolous skepticism, which gives as a reason for not attending to our obvious duties that we cannot “know” that we are not asleep, is not the lancet needed to awaken us. We are asleep as long as we are deceived, self-contradictory, inane; but Nature—which is to say, God’s will—will often prod us half-awake, “though we groan and are reluctant.”

Students of philosophy are generally introduced to the thought that life is but a dream only as an instrument of Cartesian doubt, a device to be neutralized. The more psychoanalytically-inclined commentators attribute even the readiness to consider such a theme to a deep-seated malaise, a failure of nerve in the face of worldly danger. “If only Marcus Aurelius had seen a good psychiatrist . . . ” Well, what evidence is there that psychiatrists, any more than sophists, “have the ability to impart” what they do not possess themselves, a real equanimity and knowledge of what is really ours and what’s required of us?

Descartes’ puzzle, which no modern is supposed to take seriously, is the simple question, “How do you know you are not dreaming?” The puzzle, even when it is taken seriously, is only reckoned a problem for epistemology, where the ancients recognized it as an inquiry about the status of our life-world, a problem for ethics. Descartes’ own answer (that God would not deceive honest inquirers) has not convinced many, but no other adequate response has been found. It is usual nowadays to say something like the following:

(a) As long as the “dream” is consistent and coherent, no one need care; or (b) “dreaming” only makes sense if there is such a thing as “waking,” so everything can’t be a dream; or (c) “this is not a dream” is more certain than any other premise that might be invoked to prove (or disprove) it; or (d) we cannot even speak of the possibility that we are (transcendentally) vat-brains or imprisoned spirits; or (e) things that are asleep can’t ask or answer questions (“If I ask my son if he’s awake and he says ‘no,’ I know he’s not telling the truth”). None of these claims work, even as sophistical philosophy, let alone as ways of giving the really doubtful some assurance of their identity.

Thus: there is something we call “being awake,” but the fact that we call it that no more proves that it has the properties we thereby ascribe to it than the fact that people once spoke of witches shows that there really were witches, though there were people whom everyone called “witches.” It is strange that sophists who regularly (and incorrectly) oppose Anselm’s ontological argument on the plea that reality cannot be determined simply by our concepts of reality should so unblushingly reverse their judgment when asked to consider whether this world is a dream and a delirium.

Furthermore, (a) a coherent illusion in which we have the impression that we are encountering real things, real people, can only satisfy the self-absorbed. Some of us, at least, want to have real friends and companions, and to know something about the real causes of our experience, (b) Granted that to say of an experience that it is a dream carries the implication that it is not a true waking experience, it does not follow that we can put our finger on true waking experiences, nor that they will turn out to be the ones we would have guessed. If a child is introduced to the concept of a tiger by showing her cuddly toys and gasoline advertisements, it does not follow that she cannot doubt that these are real tigers: she can, and should, (c) It may be true that the framework of our ordinary reasonings cannot be subject to the same doubts and tests that we bring to bear on elements of our experience (crudely, we check claims by seeing how well they fit together with central assumptions of “our” consensus reality). It does not follow that we can never be confronted by gross conflicts of framework and central assumptions. The thought that we are asleep and dreaming (i.e., do not have the immediate access that we had supposed to the real causes of experience) is certainly not confined to Cartesian philosophers in a skeptical mood, though it has been part of our office as “state-kept schoolmen” to help people to forget this, (d) The desperate assertion made by others that we cannot even conceive of the possibility that we are vat-brains (i.e., that all our experiences are induced in us by mad scientists tampering with the neural network of brains suspended in a nutritive solution) rests on the claim that we can never reach beyond our experience to speak of how things are. But that is itself tantamount to the claim that we are irremediably asleep and dreaming, (e) Supposing that I have a son, he may uncontroversially claim to be “awake” in the sense that he has heard what I have said, and will respond appropriately. His denial that he is awake, in context, probably amounts only to a refusal to get up or engage in conversation, a refusal to wake up to his commitments (as defined by me). If he fails to hear or to respond in rationally appropriate ways, that is evidence that he is not really awake, not really what he must be if he is to be directly engaged with the real world. If he is able to say, with some justice, that he is not awake, then he is not entirely asleep (always assuming that I am awake enough to be sure of what he said). It does not follow that he is entirely awake. Actually, if he says he is awake, he is quite likely to be wrong, even in ordinary terms. The claim that “our ordinary life-world” is the unique and unquestionable framework of all that we think and do is simple panic, and it amounts to exactly the skepticism that it seeks to allay.

To be “asleep and dreaming” is to be embedded in one’s own particularity, blind to the real world that is the ground of our experience, responsive to Umwelt-objects rather than to Reals (a creature’s Umwelt is the world of its experience, determined by its biological kind). “For those who’ve woken up there is one common world; each sleeper’s turned aside to a private one,” said Heraclitus. As we believe that we are awake we conclude that all those who do not notice or care about our objects are dreaming. We assume that people are more awake and alert the more they see things the way we “naturally” do. But we can question whether we are as distant from a direct acquaintance with Reals as we imagine them to be. We can, through the exercise of intellectual discipline, form a notion of the real world, which then serves to reveal our ordinary visions as dreamlike; But this is only believable if we have a “high” doctrine of reason, a very traditional belief that reason unites us with the powers-that-be. If we believe instead that our reasoning powers, like our perceptions, are only those expected of placental mammals in a world governed only by time and chance, then we can have no rational assurance that our most carefully experimental science has any more than local, pragmatic value. Science, on those terms, no more tells us how things are than ordinary perception does. If scientific reason gives us any access to the noumenal reality “beyond” or “beneath” our Umwelts, it can only be because that reality is not quite what scientism supposes.

We are most awake, most in touch, when our personal worlds are shrunk, and the world itself stands upright, just as it is. Our own worlds cannot accommodate that vision, which is reality itself, and so we look back on it as onto a blank—just as in ordinary dreams we cannot recall the world we mistakenly conceive to be “the one and only waking world.” We must wake up to our true identities as reasoning beings—not beings with a gift for calculation, but ones capable of the theoretical vision in which subject and object are One. Traditional philosophy consists solely in learning to know the Deity by habitual contemplation and pious devotion. “We are to stop our ears and convert our vision and our other senses inwards upon the Self,” and so mount on the wings of logos and eros to “the true object of our longing,” abolishing in thought the preoccupation of the eyes (according to Maximus): that is why, so Philo tells us, the High Priest must strip off the soul’s tunic of opinion and imagery to enter the Holy of Holies.

When we think we are awake, we think the objects we confront are ones that were there while we slept, and that causes our own perception of them. A better analysis of perception—or, at any rate, the analysis that common sense prefers—reveals that the things we perceive are not the cause but the content of our perception, the mind-realm which it is appropriate for us to have. We do not suppose that the sheep-tick’s Umwelt, its phenomenal universe, is composed of things-as-they-are: its Umwelt is how things are for a (or that) sheep-tick. We readily assume that our Umwelts; as well as being richer, are truer, and though the assumption is not strictly verifiable, we are perhaps entitled to build upon it. We could even say that what is noumenal for the sheep-tick is phenomenal for us. We can see and explain what it is whose echo or shadow’ appears in the tick-world: just so the scientist’s dream may serve to explain the ordinary human one. Those for whom the earth’s rotation is phenomenal have access to something merely noumenal for those who live on earth. We may, by extension, form the idea of entering a mode of conscious existence in which what was noumenal for us becomes phenomenal: equivalently, our consciousness is taken up into the divine mind.

To be asleep and dreaming is to have present to one objects not strictly identical with the causes of our being, and to be turned aside into our individual or species-worlds; dream-worlds are also typified by absurdity of logic and of value. It is a mark of what we see in our dreams that they do not live up to our rational demand for logical consistency. Neither does the realm we fondly call waking reality: witness standard paradoxes re change, time, and space. These are normally “solved ambulando“—which is to say, not solved at all, but consciously ignored. But there is more to the conviction that we are dreaming than logical puzzlement, just as the claim is not relevant solely to epistemology. We may also understand our ordinary goals as quite absurd—at best, quaint copies of a greater excellence: children building sand-castles to be washed away. In the words of the Nicaraguan poet Enrico Cardenal, “the realities we see are like shadows of all that is God. The reality we see is as unreal compared to the reality in God as a coloured photograph compared with what it represents . . . This whole world is made of shadows.”

We are asleep because we have false impressions, false values. It is perhaps inevitable that we should. The Lady Philosophy to Boethius:

You have forgotten what you are. Because you are wandering, forgetful of your real self, you grieve that you are in exile and stripped of your goods. Since indeed you do not know the goal and end of all things, you think that evil and wicked men are fortunate and powerful; since indeed you have forgotten what sort of governance the world is guided by, you think these fluctuations of fortune uncontrolled.

The Fall into our present sense-world, which created things as we now see them at the same moment that it created the egos that seem to see, was the product of “tolma”: the wish to control something as one’s own, even if only an apple! Whether we say, as the Gnostics and Buddhists did, that there would be no world of things at all without that error, or concede that there would be “things” of a kind—but not the things we greedily possess or hate—even without the Fall (that it was not a Fall into matter, but into sin), it remains true that what we perceive is not what the saints and true philosophers are, still less what God sees. Jung remarks, after his near-death experiences, “I have never since entirely freed myself of the impression that this life is a segment of existence which is enacted in a three-dimensional boxlike universe especially set up for it.” And again: “Our conscious world [is] a kind of illusion . . . like a dream which seems a reality as long as we are in it.” As Schopenhauer also said, “We all have a permanent notion or presentiment that under this reality in which we live and are there also lies concealed a second and different reality; it is the thing-in-itself, the hupar (the real in the proper sense) to this onar (our present life-dream).”

The first step in our return from exile is, simply, not to complain, but to hold fast to “God’s presence” in us. That presence is happiness—not as if “the substance of the happiness possessed is different from God the possessor.” Happiness, goodness, unity, and God are one and the same. “Eternity is the whole, simultaneous and perfect possession of boundless life.” That life, half-glimpsed now from the shadows, is the abiding reality of which our worlds are the stained reflections.

Morals

Are there moral dangers in this vision? Epictetus’ editor, in the Loeb Classical Library, writes: “the celebrated life-formula. Endure and Renounce, is, to speak frankly, with all its wisdom, and humility, and purifactory power, not a sufficient programme for a highly organized society making towards an envisaged goal of general improvement.” We may now, perhaps, entertain a little more realistic suspicion of “organized societies for general improvement,” and wonder, with Epictetus, whether we can really claim to be able to improve others, or society in general, when we cannot improve ourselves. But the claim that the things of this world are of little moment, that the true philosopher has other things in mind, may well seem heartless, or evasive, or (of course) incredible.

Watch yourself and see how you take the word—I do not say the word that your child is dead; how could you possibly bear that?—but the word that your oil is spilled, or your wine drunk up. Well might someone stand over you when you are in this excited condition, and say simply, ‘Philosopher, you talk differently in the schools; why are you deceiving us? Why, when you are a worm, do you claim that you are a man?’

Making oneself not mind, detaching oneself from worldly cares, is likely to be hypocritical escapism. Dodd’s rebuke: “from a world so impoverished intellectually, so insecure materially, so filled with fear and hatred as the world of the third century [what century would you prefer?] any path that promised escape must have attracted serious minds.” But do Epictetus, Aurelius, and Boethius really come across as lazy or cowardly people? Maybe, as Dodd declares, “what are we here for” is not a “question which happy men readily ask themselves”—necessarily so, if “happiness” is being absorbed by what we—for the moment—have. But those who have asked the question, and answered that we are actors in God’s play, have not obviously been the least helpful members of society. The homeland for which they have yearned, of which they have hoped to be obedient expatriates even in this land of shadows, is one where all live by their real, waking natures, which is to say, by God’s will. Skeptics—whether they are real skeptics or merely conventional moderns—will regularly reply that the inner conviction of God’s truth cannot count as knowledge. We only “know” what we can demonstrate from premises that anyone who understands them will accept. Real Pyrrhonian skeptics have a sort of right to argue like that; ordinary moderns do not, since it is quite clear that on such terms we know nothing worth remembering. The ancient quarrel between Faith and Reason rests on terminological mistakes: there is actually little difference between Nous and living faith or inspiration. “We must believe,” said Porphyry, “that in turning towards God is our salvation, as without this faith we cannot achieve truth, love or hope.”

“Even if you are not yet [a] Socrates, you ought to live as one who wishes to be [a] Socrates.” The consolation of philosophy is experienced by those who respond to God’s call to be philosophers. There can be no such duty, no such vocation, no values beyond an afternoon’s amusement in philosophy, unless Boethius and the rest were right.

If we ought to be serious and awake, it is possible for us to wake. If it is possible, then the waking world is not one alien to our best and brightest thought, and what we meet there will be the originals of which our present sense-objects are the distorted copies. If it is indeed not alien, then Epictetus was right to say that we are never helpless.

Leave a Reply