Anthony Powell’s million-word, 12-volume novel sequence, A Dance to the Music of Time, is one of the great achievements of postwar English literature, attracting near-universal praise for its subtle and textured evocation of England between World War I and the 1960’s. Powell’s narrator, Nicholas Jenkins, looks on quizzically as a representative cavalcade of 20th-century characters cavort across the pages of history, at times following anciently ordained patterns, at others striking out on their own to amusing or bizarre effect.

In the painting of 1640 by Nicolas Poussin that inspired the sequence’s name, a naked, winged, controlling Father Time strums a cithara and looks on enigmatically as dancers representing the seasons revolve, facing outward, holding hands, while a celestial chariot races through storm clouds above, and cherubs blow soap-bubbles to remind viewers of the impermanence of things. Poussin paradoxically suggests continuity and cosmic lucidity, but also the ever-present possibility of upset; dancers may perform pavanes or tarantellas, but in the end even the most corybantic must come back to the circle. Powell wrote in a comparable baroque-classical vein, as if striving to rationalize randomness, impose order on an increasingly disorderly England. Nicholas Jenkins preoccupies himself with Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), thus signaling Powell’s appreciation of the Anglican divine’s stately lugubriousness, his rolling periods and mordant sense, his insistence that everything has been seen before, what will be will be, and we should see chaos in context. Such phlegmatism pervades Dance’s million words, giving its babooneries black lustre, ballasting what in less sure hands might just have been Jazz Age incidents.

The most egregious representative of Jenkins’ England is Kenneth (Lord Ken) Widmerpool, whose altering states and styles alone adumbrate wider revolutionary changes. Widmerpool is a school contemporary of Jenkins, an awkward, ungainly, deeply earnest loner of “exotic drabness,” sniggered at or dismissed, who nevertheless “gets on” surprisingly, first in the world of business but then in other ways as his attention to tedious details and brisk officiousness help him overtake more likable but less serious schoolfellows. He is “not interested in anything not important or improving” (Powell), and constantly “closes down possibilities” (Spurling). Chilly relentlessness carries through into all he does, making him the perfect pen-pusher for peace or war, admirer of Wallis Simpson, proponent of deals with Hitler, postwar Labour peer with ties to the Soviets, cuckold, voyeur, and in the end cult thrall, returning to school-style humiliation, dying trying. He rises, and sinks, without trace. In his Understanding Anthony Powell (2004), Nicholas Birns suggests Widmerpool’s defining trait as “craven acquiescence to whatever he perceives to be the prevailing power of the day.” Yet the quintessentially 20th-century Widmerpool would have considered himself an autonomous individual and independent thinker.

This paragon of preposterousness is only one of over 400 characters populating Powell’s English universe—Widmerpool counterpointed by fusty novelists, outdated painters, alcoholic ex-gilded youths, Young Turk litterateurs, communist activists, confused peers, bed-hopping models, embittered critics, impecunious uncles, oddly impressive palmists, cranks, termagants, secretly suicidal army officers, cult-followers turned art agents, a literal femme fatale, and too many others to mention, flashing out or fleshed in expertly, each believable, comprehensible, containing multitudes. We have all had such freeze-frame encounters in strangely significant interiors, small exchanges that over time add up to an immensity—noticed similarly tragicomic coincidences, connections and contradictions, experienced the same disconcertment—as time races on while much remains the same. Those few cavilers who reject Powell for classism, conservatism, orotundity, parochialism, or triviality misread him severely. At base, Dance is a deeply humane work, a universal acknowledgement of our foibles and possibilities; as Powell wrote, “All human beings, driven as they are at different speeds by the same Furies, are at close range equally extraordinary.”

Hilary Spurling, as the compiler of Invitation to the Dance (1977), the indispensable handbook to Powell’s dramatis personæ, knows Powell’s creations better than most. “Bowled over” by Dance at 18 or 19, she worked her way onto the literary desk of the Spectator, and so was able to meet her hero. As she began to make her own name (as the biographer of Ivy Compton-Burnett, Paul Scott, Henri Matisse, Sonia Orwell, and Pearl Buck), she and her husband, John, the novelist and playwright, drew close to Powell and his wife, Violet, at liberty when passing to drop into The Chantry, the Georgian “house with a driveway” he had always sought, for tea and scintillating talk. Powell secured her the job of writing Invitation, and eventually asked her to be his biographer on the understanding, she writes, “that nothing was to be done for as long as possible.” When he died in 2000, she commissioned an outsize cast of his head, which peers onto their London garden as he once surveyed the entire city and century, a face of marked alertness, with slightly upturned nose as if still scenting all winds, and owl-like eyebrows. If Invitation allowed Spur ling to display her organizational abilities, this book proves her subtle understanding of Powell’s many milieux, and reveals a flair and force that often rival her subject’s.

An earlier Boswell-manqué, Michael Barber, found “certain doors were closed to me, and certain resources withheld.” He nevertheless published correspondence Powell might have preferred to forget, such as animadversions in the 1920’s against democracy and liberalism, and a letter of 1992 in which he opines, “much against my taste I would have been for Franco in a preference to a Left dominated by Communists.” (Spurling, loyally, does not mention Barber’s book of 2004.) Powell’s politics should not be overstressed; he was averse to all ideological or religious commitments, although he had superstitious tendencies; his sole political action was to help stave off a communist takeover of the National Union of Journalists. Unlike some of his creative contemporaries, he had no wish to reform human nature or upturn England; to borrow the title of A Dance’s third installment, his was usually an “acceptance world.” Powell produced several volumes of memoirs, but they are often opaque; as James Lees-Milne noted, Powell “discloses nothing about himself, but is revealing, albeit cautiously, of his contemporaries’ follies.” Like his creation Jenkins, like Poussin’s Time, the author was enigmatic, observing rather than acting, assessing rather than judging.

Happily, Spurling’s delicacy of touch gives us a sharp picture of Powell in his subfusc strangeness: the elfin only child, born in 1905, of an irascible and stingy army officer who had fought at Mons and his much older wife, both of whose antecessors could have come from Surtees or Thackeray; we find him forced through loneliness into feats of imagination and introspection, drawing, making up stories and reading, often books, like Aubrey Beardsley’s and Havelock Ellis’s, beyond his years, interesting himself in actual or fanciful genealogies. “He found his own obscure stability in a distant heredity,” Spurling reflects, compensating psychologically for the peripateticism of his father’s military postings by dwelling on Radnorshire antecedents “grounded for centuries.” Like his mother, he was always “glad to see ghosts.”

Powell had no fixed address until dispatched, at age ten, to a Kentish boarding school, a Spartan-to-squalid establishment whose pupils were fed rancid meats and sometimes augmented their diets with raw turnips stolen from a nearby farm. Here he befriended the novelist Henry Yorke. (The friendship ended eventually, owing to Yorke’s pomposity.) Thence to Eton, where being standoffish and unsporting he might have suffered had he not landed luckily under the aegis of Arthur Goodhart, one of the few housemasters who took more interest in the arts than in sports. Even Goodhart found the future novelist difficult to plumb, but Powell later described his Eton days as the most important of his life, when he found community and began to see the world as it was. Amongst innumerable other remembrances Powell filed away for future use was the stigma attached to Yorke, ribbed by schoolmates for unorthodox sartorial choices just as Widmerpool’s persona and even destiny would be partly determined by having once worn “the wrong kind of overcoat” at school. Mrs. Spurling has been extraordinarily assiduous in identifying the origins of numerous incidents and the originals of characters that years later would step into Dance.

Powell went on to Oxford, where he languished listlessly, conscious of being neither rich nor well-connected. But there he found Evelyn Waugh, who became a lifelong friend (and whose posthumous reputation Powell later helped rescue, thus earning him Auberon Waugh’s enmity), and other appreciators, including Maurice Bowra. And he enjoyed illuminating encounters with Dostoyevsky, Eliot, and Proust (among others) and European travel during the holidays.

After Oxford he worked at the faction-riven, stuffy Duckworth publishing house, dealing with authors whose often atrocious texts he was expected to assess, sometimes as many as 50 a week. The experience taught him how not to write, and the acquired habits of focus and swift summation were of massive benefit to him later, both as in-demand reviewer and as the author of Dance, producing installments according to a private master plan over 24 years. Friendships accrued with notables like Robert Byron, Constant Lambert, Adrian Daintrey, and the Sitwells, and he became a Territorial Army officer. Somehow he found time to become a novelist, drawing Afternoon Men (1931) from the lives around him and locations like his lodgings in Shepherd’s Market, a raffish-risqué island in the middle of Mayfair.

After a number of love affairs Powell married Violet Pakenham, the daughter of Lord Longford, in 1934. She gave him two sons and became the merciless, priceless dissector of the first draft of each volume of Dance. He tried to become a Hollywood screenwriter, and wrote four more novels—Venusberg, From a View to a Death, Agents and Patients, and What’s Become of Waring?—each in some way prefiguring his magnum opus. He got to know Graham Greene, George Orwell, and everyone else who figured on the sometimes incestuous cultural scene. (Greene fell away, piqued by Powell’s insufficiently fulsome review of The Heart of the Matter.) Even with all her access and skill, Spurling struggles at times to lift him clear of his context: He had almost too many flamboyant contemporaries, who flare up in the text and briefly outshine Powell’s steadier flame. But it would be impossible to have done a better job with so “frightfully buttoned-up” (Powell’s self-description) a subject, and in any case he is inseparable from the cultural ferment Spurling evokes so capably.

War service, though it entailed long absences and the resultant marital difficulties, also afforded a mass of material for the military-related volumes of Dance. Demobbed, Powell suffered from aimless depression and expended vast intellectual energies in book reviewing, sometimes one a day for publications including the Daily Telegraph, Punch, and the Times Literary Supplement. He became close to Malcolm Muggeridge (who, jealous of his friend’s superior reputation, later cooled on him). In 1948 he published John Aubrey and His Friends, the easygoing, inveterate quidnunc clearly speaking to Powell across centuries, and in 1951 A Question of Upbringing, with which the Dance die was cast. Between installments, Powell used his influence liberally to bolster or create careers, among them those of Kingsley Amis and V.S. Naipaul—the latter long an intimate, but eventually an ingrate who trashed Powell’s oeuvre after the death of his old mentor.

As he garnered gray hairs and honorary doctorates and was made a Companion of Honour, Powell also came to be dismissed by callower critics as fusty, outdatedly English, vaguely Tory, his European outlook and experimentalism occluded by externalities of accent or attire. (He was the last Travellers’ Club member to maintain the habit of wearing a hat during lunch.) Yet over the years when he was composing Dance his reputation generally held up, each volume awaited keenly by connoisseurs, and some awarded prizes.

Forty-two years after the appearance of the final volume, Hearing Secret Harmonies, Powell is still relatively widely read, though few artists have understood better than he the contingency of celebrity and the evanescence of fame—bubbles popping from the pipes of Poussin’s putti. Oeuvres need to be reexamined constantly, and reputations renewed, if even the greatest works of imagination are not to slide down through time’s interstices into oblivion. Spurling’s subtle salute to her friend will be of signal service to his shade, and conducive to our nuanced view of his century.

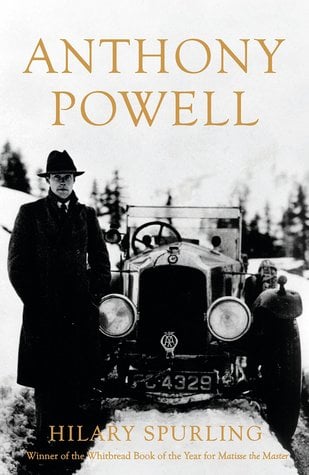

[Anthony Powell: Dancing to the Music of Time, by Hilary Spurling (London: Hamish Hamilton) 528 pp., £25.00]

Leave a Reply