Jewish stereotyping is an activity in which Jews and their enemies have both engaged. Among the self-images that Jews have popularized is that of the bookish Jewish male. The medieval biblical commentator Rashi depicts the patriarch Jacob as a scholar and homebody, “in the tradition of Shem and Eber,” Jacob’s two Semitic ancestors to whom his qualities are also ascribed. Jacob’s brother Esau was a “cunning hunter and man of the field,” and he came to represent for rabbinic commentators the hostile Gentile whose way of life was decidedly non-Jewish. The contrast between Jacob and Esau was already critical for the later prophets: Malachi, for example, states that God “loved Jacob but despised Esau,” who received desolation as his inheritance. The impetuous, blood-thirsty Esau became a symbol of what the descendants of Jacob were to fear, and the rabbis saw that enemy as variously incarnated in Israel’s Edomite neighbors to the South (supposedly descended from Esau), the Roman Empire, and the medieval Church. All of these groups were identified with the color red, going back to Esau’s association with the pot of lentils in return for which he sold his birthright to Jacob. (The Hebrew word for lentil, adom, can also mean red.) All of Israel’s political foes, moreover, were seen as sanguinary and unreflective, in contrast to Jacob’s scions, who were shown cultivating sedentary, domestic virtues.

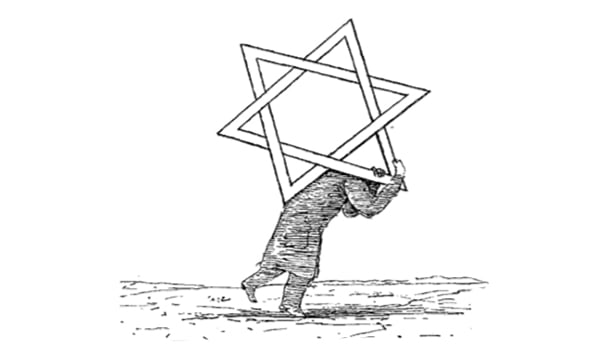

The Jewish self-image is of course tied to the stifling of Jewish masculinity that was evident by the Middle Ages. The received view, which the Zionist movement has stressed, is that Jewish manhood was stunted by the restrictions that a hostile Christian world placed on Jewish society. This view is partly correct. The prohibitions imposed on Jews in medieval Europe—against owning land and bearing arms—prevented Jewish men from tilling the soil, practicing self-defense, and engaging in other manly pursuits. In the proverbial Jewish family of the Eastern European ghetto, the wife ran a business and the husband pored over Talmudic texts. This division of labor was both the product of prolonged social discrimination and a creative adaptation to an unfriendly environment.

But that family pattern, as Jacob Neusner demonstrates, was already there, at least embryonically, centuries before, in the Talmudic reconstruction of Jewish culture. In the face of successive defeats—the destruction of the Second Temple and of the Jewish Commonwealth and the rise of an ungrateful daughter religion—the authors and redactors of the rabbinic texts shifted the emphasis in Jewish life from national resurrection to the study and performance of detailed rituals. As this became the focus of Jewish life, it was also necessary to recreate biblical role models: thus the warrior King David is depicted as a proto-Talmudist, like the son of Noah, Shem, and Shem’s grandson Eber. Anything orienting Jewish life toward military affairs is kept out of the Talmudic prescriptions: King Messiah, for example, is exalted as a future respondent to legal conundrums but never as a warrior.

These interpretive traditions are critical for understanding modern stereotypes (and self-stereotypes) of Jewish masculinity. The polarity constructed between Jacob and Esau returns in a provocative fashion in Nietzsche, for whom Jews became the destined priests of slave morality. Unlike the joyous warrior who innocently and instinctively vents hostility, Jews, Nietzsche explains, have learned to fight by cunning. They manipulate the “bad conscience” of others, which they have shaped by introducing “guilt,” “sin,” and other servile concepts. Jews are accused of making the West ashamed of the Hellenic worship of physical beauty and of supplanting a virile civilization with the ideal of self-mortification. With due respect to Nietzsche’s “liberal” interpreters, these criticisms are not directed at Christians first and at Jews secondarily. True, Nietzsche deplored anti-Semitism, but he also leveled numerous attacks, particularly in his correspondence, on Judaism as the source of Christian self-debasement. He also mocked Jewish cunning and lack of aristocratic virtue.

As a recently published French anthology of essays, De Sife-Maria à Jérusalem: Nietzsche et le juddisme (edited by Dominique Bourel and Jacques Le Rider), makes clear, Nietzsche’s ridicule of the Jews made a deep impression on early Zionists, who were drawn to Nietzsche for his lyrical style and anti-Christian neo-paganism. For these Zionists it was important to meet Nietzsche’s criticism by reconstructing Jewish identity in a Jewish homeland. Even the socialists among these Zionists thought Nietzsche had made valid observations about the unnatural mentality of their fellow Jews, even if he had also rejected socialism and liberalism.

It is not surprising that the candidly self-hating Jew Otto Weininger, in Sex and Character (1903), should dwell turgidly and splenetically on the problem of feminized Jewish men. More interesting, in 1905 the father of what later became the Zionist right, Vladimir Jabotinsky, proposed as basic to his nationalist movement the achievement of Jewish remasculinization: “Our starting point is to take the typical Yid of today and to imagine his diametric opposite. Because the Yid is ugly, sickly, and lacks decorum, we shall endow the ideal image of the Hebrew with masculine beauty. The Yid is downtrodden and easily frightened, and, therefore, the Hebrew ought to be proud and independent.”

Freud also read Nietzsche on the Jews and believed what he read, to the point that he sought physiological explanations for the “feminization” of Jewish males. According to Sander L. Oilman in Freud, Race, and Gender, the father of modern psychology long agonized over the “proneness to hysteria” and other “female qualities” that he thought typical of Jewish men. He found these qualities, which he identified with his own father, embarrassing, and he speculated on how they might be removed provided they were not part of an “immutable biological construction.”

In recent years this issue of feminized Jewish males has reemerged in a different context: an intramural Jewish dispute over contemporary Jewish identity. Neither side in this dispute is particularly pro-Western: both view Western Christian society as a continuing fount of anti-Jewish sentiment. But for one side Western Christian hostility is responsible for Jewish feminization, while for the other it produced the forced masculinization of a once “sensitive” Jewish culture. The sides are presented (or present themselves) as “tough” vs. “soft,” or in Yiddish, “starke” vs. “schwache.” Meir Kahane’s Never Again and Ruth Wisse’s If I Am Not for Myself: The Liberal Betrayal of the Jews are representative of the “tough” Jews; Paul Breines’ Tough Jews: Political Fantasies and the Moral Dilemma of American Jewry and the writings of Jewish feminist Letty C. Pogrebin exemplify the “soft” thinking.

Having forced myself to read such polemics, I am struck more by the similarities than by the differences between the two sides. Both are fixated on the insidious presence of anti-Semitism and express Jewish alienation from Gentile society, but both also reveal no positive religious elements. Wisse and Kahane, though residing in North America, scold other Jews for not recognizing Israel as their only homeland. For both of these toughs, Arab opposition to Israel is derivative of Christian anti-Semitism, which also informed the Nazi movement. As Wisse, a frequent Commentary contributor, puts it: “The Arab charge that the creation of Israel is a crime against an Arab people has much in common with the earlier Christian charge that the Jews denied the son of God, or that of the Nazis that the Jews polluted the Aryan race. These charges are unanswerable except through dissolution of the Jewish religion, the Jewish people, the Jewish state.”

Though the softs seem to like what Wisse condemns, a “Jewish civilization of self-blame,” and what Kahane presents as the “victory of Hellenism over the Jewish people,” clearly the two sides agree on other matters. For toughs and softs, the victory of the left throughout the West would not be a bad thing, as long as leftist anti-Semitism were controlled. For the softs, conservative movements are inevitably unkind, anti-feminist and anti-Jewish. In Breines’ words: “A critique of tough Jews ought, then, to begin and end with a summons gently to abolish the conditions that generate toughness.” A continued alliance with international socialism and feminism, argue the softs, helps Jews and other oppressed minorities. It weakens traditionalist cultures in which Jews have been disadvantaged, and so Zionists should aim at cooperation with social and cultural progressives everywhere. Though Breines is more sympathetic to “feminized” Jewish males than Wisse or Kahane, his reasoning is also anchored in an appeal to Jewish self-interest. Like the toughs, Breines thinks Jewish interests are best protected where Gentiles are not allowed to be their unruly selves.

In a perceptive review of Wisse’s book, Allan C. Brownfeld makes the point that “for an academician of note, Wisse’s discussion of liberalism is largely superficial. She does not properly differentiate between the classical liberalism of the 19th century . . . and the statist liberalism of the 20th century.” Moreover, “what seems to disturb Wisse most is the classical liberalism which ended the theocratic exclusion of Jews from the life and culture of Western Europe. She seems to long to restore the ghetto walls, which maintained the kind of artificial Jewish unity she would like once again to impose.” What Brownfeld might have added is that Wisse and other Jewish toughs are producing their own Jewish counterpart to black separatism: presenting Jews as Western victims, who are to be indulged no matter what they demand, whether it is the right to view themselves as embattled anti-Westerners condemning their loss of collective identity or only a universal attention to their concerns. Brownfeld is right that Wisse has fewer reservations about contemporary than about classical liberalism. The old liberalism brought Jews into a European middle-class civilization that she wishes to have them forget. The new liberalism, though sometimes allied with the Palestinians, features the kind of victimology in which Wisse feels most at home.

As for the debate about the feminization of Jewish males, it might be best to pursue it under different auspices. Toughs and softs are both Jewish victimologists wearing interchangeable masks, like feminists and men’s rights groups. One even finds the same Jewish figures combining soft and tough stances, e.g., Alan Dershowitz, Abe Rosenthal, and Martin Peretz, all social liberals who are Zionist hawks. Here the affinities to Afro-American nationalism are all too plain. In both cases the most militant and easily offended nationalists feel a natural pull in America toward the victimological left. That pull is subject to change only when the left favors some other victim group at the expense of one’s own. But as soon as that sense of slight passes, the militant, alienated majority again aligns itself with the left.

Thus Jewish toughs and black power advocates typically identify themselves with the same political side as gays and feminists. Alienation is a stronger theme in both instances than the cult of masculinity. Both Wisse and Kahane rebuke Jewish liberals for not being sufficiently suspicious of Gentiles. Liberalism, for these toughs, would be fine, so long as it incorporated enough Jewish suspicion of Arabs and their Western Christian apologists. This tough position is entirely consistent with the liberalism it never gets around to criticizing. It is in fact parasitic on that liberalism, like black separatists and Irish American supporters of both the IRA and Ted Kennedy. Behind all these shows of masculine toughness is the same whining by self-designated victims, much of it intended for guilt-obsessed WASPs. And the point of this whining is always the same: certain victims are not getting enough attention and refuse to be Uncle Toms. This may exemplify the proneness to hysteria that Freud believed afflicted only Jewish males.

I close this essay with one critical observation about the best of the works studied in the course of my research: Paul Breines’ Tough Jews. In a detailed discussion of American Jewish schlock, Breines notes the continuing popularity of tough Zionist novelists like Leon Uris, Gloria Goldreich, Ghayym Zeldis, and Joel Gross (the most prototypical of these authors, Ben Hecht, belonged to an older generation). Such novelists appeal to aggressive Jewish nationalists in America, who are always criticizing fellow Jews as “self-hating.” Breines observes the cultural resentment abounding in some Zionist novels, which invariably treat German Jews as Uncle Toms and the old Protestantized American Jewish elite as even worse. The aesthetic and moral judgments here are certainly sound, but Breines ascribes too much of a consistent rightist gestalt to his subjects. Are they psychological “fascists,” as he seems to suggest, or just too contradictory and too trivial to be assigned ideological labels?

And was that ardent Europeanist and despiser of communism, Zev Jabotinsky, the spiritual ancestor of the tough Jews who read and write hyper-Zionist schlock? The pre-World War I generation of tough Jews whom Breines cites faced real existential and cultural problems: their identification with Western thought in a society that was largely non-Westernized and the task of transforming that society, to which they felt morally and ancestrally bound, into something that they could admire and that also would survive its enemies. In no sense did Jabotinsky, a multilingual novelist who felt at home in most of Europe, foreshadow the American ghettoized schlepp who reads Goldreich, Zeldis, and perhaps Ruth Wisse: i.e., one who gets macho kicks out of accounts about how Israelis shoot Arabs or capture Nazi scientists before attending meetings of NOW with his opinionated, bleached-blond wife. Breines’ genealogy is wrong for at least two reasons: first, he goes too far in demonizing Jabotinsky’s and Freud’s Jewish self-criticism, and then he assigns too much theoretical importance to those who are better left to satirists. As one Austro-German Jew to another, I would urge Breines to lighten up and take schlepps less seriously.

Leave a Reply