For at least a decade, a changing political climate has been upsetting the media and the practitioners of politics as usual. Populist movements have been spreading through the West under such names as the Lega Nord (Italy), the National Front (France), Freiheitliche Partei (Austria), the Reform Party (Canada), and Pat Buchanan’s American Cause. Though there are critical differences among these movements, their shared characteristics seem more important. All of them attack elitist impersonal bureaucracy and treat established parties as shills for special interests. As the onetime theoretician of the Lega Nord, Gianfranco Miglio, points out, Italy has ceased to be a country and has become instead a “corrupt feudal arrangement,” run by party bosses and their administrative lackeys.

Populist movements feature charismatic leaders (an exception being the emaciated, bespectacled head of the Canadian Reform Party, Preston Manning). Whether the Frenchman Jean-Marie Le Pen, the Lombard Umberto Bossi, the Austrian Jörg Haider, or the American Pat Buchanan, the people’s self-described spokesmen rail against “undemocratic” forces, particularly self-described democratic governments which insulate themselves against the popular will. Like their late 19th-century counterparts, today’s populists appeal to identitarian democracy. Real democracy, they insist, is about self-identified communities being governed by ancestral wisdom. Democracy is not about being “sensitive,” as social planners and behavior-modifiers believe; nor is it about keeping one’s borders perpetually open to newcomers who may fundamentally change the societies they enter.

Among populist advocates, Pat Buchanan has elicited the most widespread and most panicky responses. Usually serious journalists have compared him to Adolf Hitler, and hardly an hour goes by without a public personality warning against his “racism,” “anti-Semitism,” or “Catholic authoritarian personality.” All such diatribes contain gross exaggeration or outright lies, but they do fit a widely shared and not entirely fictive view of populism. Some of the most frightened anti-populists are Jewish and assume a necessary link between culturally conservative majoritarianism and anti-Semitism.

In response to this fear, based partly on true memories from other times and places, Jews have associated their safety, as Benjamin Ginsberg and Stanley Rothman note, with highly centralized bureaucratic government and with anticlerical politics. And one contemporary populist movement, the National Front, has solidified Jewish liberal opposition by responding to its Jewish critics with brutal ridicule. In the last nine years, the Front’s leaders have gone out of their way to insult Jewish sensitivities, as an expression of contempt for those they believe are defaming them. Despite this fighting, in which Jewish groups have called on the French state to suppress the populist right, Le Pen continues to have Jewish economic advisors. He also wonders why French Jews intensely dislike him, given his resistance to Arab immigration and the fact that French Jews have been targeted by Arab terrorists.

But America is not France and does not carry its anti-Semitic baggage, which may nevertheless be exaggerated for ideological reasons. Despite abrasive remarks about AIPAC in 1991, Buchanan is not an anti-Semite. About half of his inner circle, which includes a Hasidic rabbi, is Jewish, and his praise for the present Israeli government is even more extravagant than was his criticism of the former Likud regime. The charge of racism leveled at Buchanan seems likewise problematic. Not only have black liberals like Juan Williams rushed to his defense, but it is also hard to find insulting comments by Buchanan about blacks (save for deviations from p.c.). The charge that some of his followers are anti-black proves little indeed. It involves a standard of conduct that liberals would hardly apply to themselves. After all, they do not hold it against Clinton that he wins with the support of outspokenly anti-Semitic black leaders. Besides, Buchanan appeals to all critics of his enemies, from Christian homeschoolers and black evangelists to white supremacists. But he has not set out to court specifically this last group, unless his kind references to Confederate bravery are given an unjustifiably sinister meaning. At the same time, Buchanan and his sister Bay have made special efforts to attract socially conservative blacks.

The media are right to fret about populists, but not for the reasons they give. For 80 years or more, democracy in Western countries has been increasingly identified with social planning and human rights agendas. Most of this democratic project has assumed a captive public, and John Gray correctly observes that for modern liberals, all political first questions must be kept out of public contention. They are questions of fundamental right or social policy, which liberals hope to see settled “pre-politically,” i.e., in courts or by administrative experts. The media have benefited from this arrangement, by becoming powerful guardians of “liberal democracy.” They set the parameters of “sensitive” political discourse and bully politicians and judges into accepting their private opinions. They also pretend that their undemocratic will is what the people really want. They are therefore free to ignore the discrepancy between their own social morality and what most people seem to believe. And despite their astronomic salaries and defense of entrenched bureaucratic power, as S. Robert Lichter proves in The Media Elite, media personalities and journalists think of themselves as threatened champions of the dispossessed.

Populist leaders delight in going after such pretensions. They ridicule journalists and mediacrats as royalists and, in the savage phrase of Sam Francis, “the priesthood of the managerial state.” Most distressingly for their verbalizing enemies, populist parties are no longer on the electoral fringe. In France, Italy, and Austria, their candidates win between 15 and 40 percent of the votes cast in national elections. In Italy, both regional populists and neo-fascists have entered ruling coalitions, and there the measures aimed at restricting immigration and parliamentary discussion about a decentralized Italian federal government underscore the impact of populist politics.

Despite the electoral rise of populism, counterrevolutionary democrats must still define themselves coherently. They are still in some cases driven by those reactions that pushed them into prominence. In trying to woo protest electorates, at least some populist leaders too often oscillate between opposing stands. They talk about overthrowing the administrative state while promising social programs and federal bans on abortion. The same inconsistency plagues both Buchanan’s campaign and the National Front. Ten years ago Le Pen, who was then focusing on a largely upper-middle-class and professional electorate, favored détatisation and a French federal administration restricted to listed and specific tasks. By now, as the French historian Franklin Adler demonstrates, the lepénistes have gone from presenting themselves as opponents of crime and immigration to replacing the collapsing French left, as protectors of social pensions. Though populists have recruited a blue-collar base by appealing to traditionalist themes, they have also won this base in France and now in the United States by imitating socialists.

But can they play this card without surrendering even more power to an elite they claim to despise? And though one can make an impeccably communitarian argument for trade protection, as Le Pen and Buchanan have done, would such a policy leave a federal administration subservient to popular control? It is hard to see this happening, even if NAFTA and GATT are as flawed as Buchanan suggests. And would Buchanan, by turning over the matter of abortion to the federal government in his best-case scenario, be resisting Washington? This does not seem likely, when the constitutional alternative is having state legislatures decide a morally divisive issue.

Populists are also struggling to define identity in a future populist regime. Here, difficult choices must be made. A regionally based populism, as advocated by Northern Italian and Austrian populists, cannot be the same as a nationalist populist movement, as illustrated by the American Cause, the F.N., or the Reform Party in Canada. Some populist leaders fudge the issue, by trying to have it both ways. Buchanan, for example, has defended the use of the Confederate flag and celebrated his own Confederate ancestors while campaigning in the South; he has then turned around and made Lincolnesque speeches about a tightly unified American nation, whose federal administration will be asked to protect family morality. In Canada, Manning has championed Anglophone minorities in Quebec while calling for a stronger federal government; he has then denounced administrative overreach and promised to end it.

Outside of the well-educated and predominantly upper-middle-class Northern League and Freiheitliche Partei, most populists have blinked a question that will not go away. Is a retreat from administrative overreach possible without structural change? The answer seems to be no: unless citizens have a sense of who they are and some way of reining in government, the populist turn will not likely lead anywhere. Regional populism, it may be argued, is the only kind that can provide a counterweight to public administration. The smaller the region, as Aristotle taught, the more thoroughly will the inhabitants resemble an extended household.

But there are circumstances working against the regional option in the United States. With a mobile population, national communications network, and an international economy, it may be hard to recreate the kind of regional solidarity needed to curb federal administrators and federal judges. It is also questionable whether the states can be made to play such a role. They, too, have footloose inhabitants, a dwindling cultural sense, and administrations which are often mere imitations of their federal masters. Appeals to the Tenth Amendment and dual federalism may hold off federal power from time to time, but without a self-identified regional base, states and collections of states will not long resist central authorities.

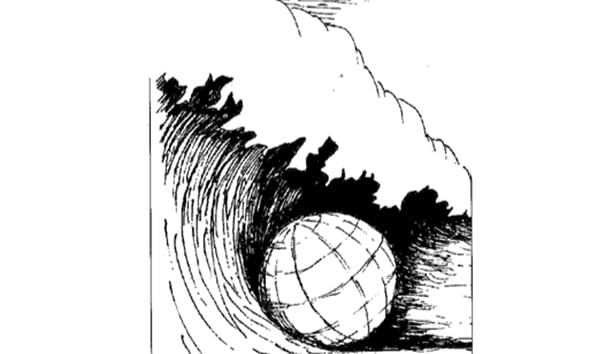

Without a plan for getting these authorities off our backs, American populists nonetheless try to pursue identitarian politics. Given the diversity of the “American people,” this has not been easy; and for want of another tie that can bind, religion for the time being has become the foundational identity around which Buchananites rally. They speak of cultural wars to be waged on behalf of Christian or biblical values that the liberal left scorns and seeks to remove from public life. We are also warned to protect ourselves against a New World Order, which threatens an identity that is treated as more or less apodictic. The reality is far messier. The identity being assumed is far from obvious to most voters who, if the polls are accurate, care more about material concerns than either national sovereignty or moral identity. Though cultural issues have intrinsic importance, in the United States they are still attached to what is only a protest movement. Unlike the populism of the 1890’s, rooted in the Plains and in the South, today’s populists do not have a regional base or even a memory of decentralized government.

My point is not to run down the only populist alternative Americans have thus far been able to rear up against the federal behemoth. Despite its defects, this populism does provide an insurgency against rule by “buzzing fax machines in D.C.” Its representatives, moreover, raise a critical question about citizenship: whether authentic democracy is compatible with having citizens socialized by those who are supposed to be their servants. The populists keep reminding us that there is an honorable democratic right to reject immigration and seal one’s borders. On all these points and more, the Buchananites have challenged the “pre-political” paradigm of democracy. The managerial state under which we and they live has not brought about the “end of ideology.” Instead, it has given us thought control, together with soaring public debts and growing dependence on the public sector. For all of their flailing about, Buchanan and his followers at least know what ails our political life.

But American populists must move beyond mere protest politics. They will have to come up with something else for what they intend to replace, and this will be a far more arduous task then sparring with overwrought journalists or responding to Bill Safire’s hyperboles. In Milan, a committee of legal and constitutional scholars undertook in 1981 to draft regional alternatives to the Italian republic. Their completed work has served as the blueprint for a constitutional proposal in which historical regions are to be given back a high degree of self-government. Right now the Italian assembly is considering this proposal. Though an Italian project cannot be wholly transferred to the American context, it does suggest possibilities for an improved American populism. Like Italian populists, American ones should insist that true self-government can only work territorially. It is about devolution of power—and not about conquering the world for a “democratic” empire. It is also about citizens controlling their own population, as opposed to the ideal of open borders. In a recent syndicated column, Ben Wattenberg accused Buchanan (and by implication, his followers) of being “a democracy trasher feasting on the fruits of democracy.” The best response is not a sneer but the initiation of a public debate about the meaning of democracy. Buchanan’s respectful opponents are inviting him to engage in such a discussion, and the presentation of views, if one is to be given, should be worthy of the occasion.

Leave a Reply