Does the public get the books it wants? Publishers, in their own interest, make it their business to see to that, whether it is a question of chemistry text-books or novels. While recent sales of earlier textbooks can suggest what the market will be for new ones, when it comes to fiction, publishers must play their hunches, taking into account current tastes and trends. What is needed, for a book that hundreds of thousands will buy, is either a well-known name that acts like a magnet, or a sure best-seller formula, or some quality that, via publicity and reviewing, can lift it into the public imagination. Established favorites often win at the literary racetrack, of course; sometimes, gambles lead to nothing; other dark horses turn out to be winners.

This dark novel by Diane Setterfield, who was born in 1964 in Berkshire and lives in Yorkshire, is a winner, for her and also the publishers, doubtless. The manuscript was the object of a bidding war in both Great Britain and the United States. Ultimately, Orion paid her an advance of 800,000 pounds sterling for the British rights, and Simon & Schuster, which owns the Atria imprint, one million dollars for the U.S. rights. These extraordi-nary advances to a previously unpublished author say much about publishing and the fiction market. The book topped the best-seller lists in America, but, as British commentators remarked, sales have been more modest in England. A paperback edition is to appear in October 2007. An abridged audio version with Lynn Redgrave, an unabridged version, an e-book, and a Spanish translation already exist.

The Thirteenth Tale, which takes place chiefly on the Yorkshire moors, is a Gothic novel of suspense and horror. That is a selling point; the Barnes & Noble website says that admirers of Charlotte Brontë and Daphne Du Maurier will enjoy this book. Setterfield told an interviewer that, as a university student, she bought only books identified as classics rather than investing in contemporary fiction. Among fictional antecedents mentioned within the book are Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, The Woman in White (Wil-kie Collins’s 1860 detective novel, a very early example of the genre), The Turn of the Screw, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and The Castle of Otranto (by Horace Wal-pole, 1764). To speak of antecedents is not to suggest lack of originality; the author’s adaptation of fictional patterns and conventions is brilliant. As Vida Winter (a character) observes, all stories derive from others. Vida cites, among the basic plot patterns of European tales (which have been analyzed in fact by contemporary structural narratologists), the pattern of three (subtly visible here): three sons or daughters, three tests, three adversaries. Jane Eyre is mentioned frequently; a governess reads from it to her young and impressionable pupils—surely a strange choice—and a page torn out has enigmatic meaning. Further similarities to Gothic fiction include equivalents to the “madwoman in the attic.” (One character is confined to an asylum.) Others lock themselves in or are forced into seclusion; one seems to be an apparition; a set of twins is half-feral. Add to that a ruined house, a destructive fire (arson) and attempted murder, apparent magic and ghosts, a foundling, unspeakable crimes—almost surely, incest and rape—births shrouded in fog and strange deaths, and other hidden facts that only gradually and circuitously come to light.

The structure is a frame-narrative, with frequent switching from outer to inner story and thematic connections between the two, almost eerie. Margaret Lea, the first narrator, to whom the second, Vida, tells her story (the more important), is not merely a passive auditor; Margaret, who also searches for part of her past, must play the role of detective because Vida, having lived a lie and then, as a novelist, made a career out of storytelling, is untruthful, even as she expresses the desire to reveal herself. Layers upon layers must be peeled back. Setterfield’s handling of Margaret’s discovery process, which relies partly (the reader finds) on Vida’s subtle switching of pronouns, is very skillful. The author eschews narrative cheating—deliberately planting false clues—but readers can be easily misled, as is Margaret, and are teased by intricacies in the plot.

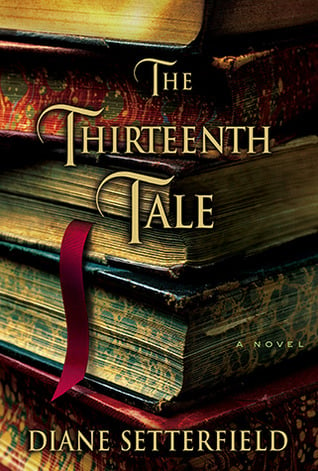

The references to earlier suspense fiction are repeated in the manufacture of Setterfield’s novel. The dust jacket shows a stack of old volumes, recognizable by corners of bindings and the mottled green-and-white or red-and-white markings along the page edges. The novel is bound in old-fashioned maroon, and the spine has gold lettering and a design reminiscent of much earlier books. Furthermore, in a clever technique that raises a fictional character onto the plane of apparent “reality,” Setterfield, or her advisors, chose to have a quotation from Vida on the back cover; another serves as the epigraph. The cover-four quotation is not, however, promotional—Setterfield stops short of having her character praise the book—but rather a general statement about truth and fiction, drawn, like the epigraph, from the text. If one accepts the old convention of the found or passed-on manuscript, the quotations are justified, since, as the last pages reveal, the text is, ostensibly, an account written up by Margaret from extensive notes she took while Vida recounted her story, and is to be given to heirs, who may publish it if they wish.

It is of more than passing interest that Setterfield took a B.A. and then a Ph.D. in French at the University of Bristol. For her thesis, she wrote on André Gide’s use of the mise en abyme (a term from heraldry to which he gave a special meaning)—that is, reproducing at a second narrative level plots or features from the first level. Setterfield taught French and wrote academic papers before leaving the profession to devote herself to fiction. She has observed, quite rightly, that, by working with a foreign language, one comes to understand better one’s own and has acknowledged some influence from French, though more in the process of composition than in the result.

Reading The Thirteenth Tale, one is tempted to look for Gidean narrative techniques, perhaps as illustrated in Les Faux-Monnayeurs (The Counterfeiters, 1925). Indeed there are similarities: stories-within-stories and, thus, multiple narrators; fragmented narration; changes in perspective; quotation of letters and diary passages; and various echoes and mirror images, used by others but illustrated particularly well by Gide. Gide, who assessed his characters within the novel and in Journal des Faux-Monnayeurs, would have appreciated, presumably, the appearance of Vida in both the inner story and the extreme outer one, that of “reality,” where Setterfield can, ostensibly, quote from her. This blurring of narrative boundaries is not new, but Setterfield’s novel does illustrate it cleverly.

Setterfield has alluded explicitly to connections between her work and both the mise en abyme and the psychic phenomenon that Gide called dédoublement, or doubling of the self, saying that she recognized her own experience in his. Gide used the term in reference to the feeling he got, on occasions, of being not wholly present and engaged—of being outside an action even as it happened to him—and, thus, double, both participant and witness, on an uncertain footing of being. In The Thirteenth Tale, Margaret, the daughter of an antiquarian bookseller, is a bookish person, living chiefly through what she reads; imagination offers a reality that she observes but cannot live fully. In addition, the theme of twinning—there are two pairs—produces variations on doubling, including that of the Doppelgänger. Mirror motifs, common in Gide also, offer other instances of doubling. In terms of general atmosphere, if one wishes to find a precedent for Setterfield’s novel among Gide’s, it is his short novel Isabelle (1911), similarly concerned with a mystery in a country house and illegitimate birth. A character in Vida’s story is named Isabelle.

The tone and topics of The Thirteenth Tale are in fashion, literary and otherwise. Ours is not an age of mens sana, rationality, and goodness. Think of the phenomenon of repressed memory, by which adults recall or, more likely, invent former experiences and postulate another self. Think of the popularity of witchcraft; the English department at my erstwhile university offered a course on witchcraft literature. Film noir, black jokes, magic realism, astrology, devil fixation, fascination with Halloween, “Goth” attire and body puncturing, violence in the streets and in aural and visual media, the promotion of deviancy and horrible crimes (including mutilation and serial killing), and the public’s ghoulish interest in them—all these phenomena and more, whether by name, content, or both, are evidence of fascination with, and indulgence toward, the unhealthy. (Kevin Costner is quoted as saying that he sometimes “roots for” the serial killer he plays in the recent film Mr. Brooks.)

Does the taste for darkness and the enigmatic, for transgressing boundaries, spring from the mystery of life? Life has always been mysterious. Of course, fiction and drama depend largely on the struggles between opposing forces, and sometimes, full-blown evil appears; but it is traditionally punished, even if, as in Greek tragedy and Shakespeare, the good are victims, too. The triumph of order over disorder, even at an awful price, is psychologically and morally satisfying, as Aristotle observed in writing about catharsis. What is not suited to our nature is perversion and its glorification. While, in Setterfield’s novel, the ironies of events mean that the good may suffer, there are numerous satisfying outcomes, and wickedness does not survive to flourish another day; if one accepts certain genetic theories, evil is even explained, or, at least, its cause pushed back, in the case of the twins conceived by incest between two sadomasochists.

Another British novelist, Joanne Harris, who has been at the top of the London Sunday Times best-seller list, has similarly drawn for her work on disturbed behavior, magic that appears operative, and downright wickedness. Chocolat, which sold well on both sides of the Atlantic, was “dark and mystical,” in one commentator’s words; subsequent novels, especially Gentlemen and Players (2005) and The Lollipop Shoes (2007), deal with superstition and unhealthy manipulation of others through trickery, and allow amorality, even evil, to prosper; as one heroine says, “Murder is no big deal.” It is a coincidence that Harris was born in 1964, like Setterfield, but perhaps not that she studied modern languages (Cambridge) and taught French language and literature: French examples may have helped her learn to handle complicated narratives. One does wonder, however, what it is that leads apparently sane women to find satisfaction in the evocation of the paranormal and creation of perverted and wicked characters. (Each insists that she does not write simply for money or fame.) One can ask the same concerning what leads the public to read about them.

Well adapted to various voices, Setterfield’s style is supple and perspicacious. She describes beautifully, for instance, the effect of rain on an image in a window and sees a disease as a “distillation”: “The more it reduced her, the more it exposed her essence.” The diction fits a pseudo-19th-century novel, without the vileness of much modern fiction. Occasional colloquialisms—such as cope used absolutely, and other slips—are small flaws. What mars the writing frequently is the violation of grammatical rules, surprising in view of the author’s education and the level of language displayed otherwise. Surely someone such as Margaret, who dotes on 19th-century British fiction, would be aware of proper usage—lie, not lay, as the intransitive verb, and the subjective case after to be, than, and as . . . as and similar constructions. The French model does not excuse these mistakes. Gide would not have made grammatical errors.

The broad reading public does not, of course, care. What can be said for Setterfield’s novel is that it appeals also to more discerning readers, especially those who like the tradition of Gothic fiction; they will be well pleased with this book.

[The Thirteenth Tale, by Diane Setterfield (New York: Atria Books) 407 pp., $26.00]

Leave a Reply