At the end of October, President Joe Biden signed an executive order for the creation of new standards on security and privacy to ensure the safety of Americans with the rise of artificial intelligence. The initiative called for assessing potential national, economic, and health risks associated with the technology.

It seems to me, however, that this genie left the bottle long ago. Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, even admitted he’s “a little bit scared” of ChatGPT and the ferocious speed at which it has developed. When asked who should regulate this kind of technology, Altman proposed that compliance and enforcement be overseen by an international body of world governments and institutions. His answer, ironically, sounded a bit like something ChatGPT might spit out—centralizing in its direction and utopian in its vision.

And that is the paradox of artificial intelligence (AI). Unleashed by our desire for convenience, empowered by our dream of emancipation from toil, AI is forging a world less free, and filled by individuals less equipped for freedom—or simply less equipped, period.

AI creates our grocery lists, books our trips, plots our courses, “personalizes” our feeds. It can do our homework, write our poetry, and produce our art. Now, everyone is worried about a Terminator-style Skynet AI become self-aware and kicking off a nuclear holocaust. But in some ways, the issue is more insidious.

Consider our global positioning systems, or GPS, which are now so ubiquitous one hardly gives using them a second thought. If during a conversation on the dangers of AI you were to interject with a rant about digital navigation systems, you’d likely generate an eyebrow or three raised aloft on the faces of your interlocutors. But the consequences of capitulation to navigation systems are potentially graver than people realize.

In a 2021 article, “How GPS Weakens Memory—and What We Can Do About It,” Scientific American explained:

There are structures in the brain dedicated to these complex pathfinding tasks. In particular, the hippocampus is deeply associated with supporting spatial memory, spatial navigation and mental mapping.

There is an intimate connection between navigation and memory, a relationship perhaps best illustrated by the method of loci. The loci method is a mnemonic device adopted by the ancient Greeks and Romans to retain information through visualizations of spatial environments. It works like this: Imagine yourself in a very familiar setting. A home, a shop, anywhere you know well. In this space, your “memory palace,” information is attached to various locations. Each room contains something. To recall an item, you mentally stroll through these loci. Cicero used this technique to perfect his rhetoric.

If GPS is flattening our mind palaces, it’s probably because it’s flattening our brains. “Expert navigators such as London cab drivers have larger hippocampi compared to regular populations in consequence of their intensive spatial mapping and multisensory experience of the city,” according to the Scientific American article. I suspect the cab drivers will be the last of us to avoid early-onset dementia.

Technology is also shaping our opinions in ways subtler than we realize, through tools that are intended to streamline the workflow, like Grammarly.

More than 30 million people use Grammarly’s AI for their written communications, from emails to essays. The program alerts users when they are employing language considered by the LGBTQIA+ community disrespectful, offensive, or outdated. “Our goal with these suggestions is not to force you to write a certain way but to ask you to take a moment to consider how your audience may be affected by the language you choose,” according to a company statement released during the June 2020 “Pride” month.

But those suggestions are framed in a way that feels like being asked to meet with HR, nudging users to make a particular choice. Do you really want to use language some may find offensive, hurtful, or exclusive? Avoiding a faux pas is as easy as accepting Grammarly’s suggestion to alter what you have written. Over time, your opinions will change, too. “Language,” wrote Heidegger, “is the house of being. In its home human beings dwell.”

Grammarly’s AI polished your writing, sure, but it also changed how you see the world by changing the language you use to describe it. As an adult who is aware of and can ignore the LBTQIA+ propaganda, this might seem like a nonissue. But think of the young professionals, the high school and college students, who will use it and perhaps be shaped by it.

Today, we are always plugged-in, perpetually stimulated, and constantly influenced by technology designed to work for us, though we increasingly find ourselves working for or dependent on it. This might come as a surprise to Aristotle, who speculated that automation had the potential to eliminate slaves and masters:

If each instrument could do its own work, at the word of command or by intelligent anticipation, like the statues of Daedalus or the tripods made by Hephaestus, of which the poet relates that ‘Of their own motion they entered the conclave of Gods on Olympus.’ A shuttle would then weave of itself, and a plectrum would do its own harp playing. In this situation managers would not need subordinates and masters would not need slaves.

In our time, however, man’s confrontation and assimilation with technology has turned him into an automaton. By allowing technology to think and leap into action on his behalf, man is reduced to a passive recipient of suggestions handed down by algorithms. It has made life easier, but it also threatens to deprive us of something important. Or as Atreyu puts it in The Neverending Story, “It gives you the means, but it takes away your purpose.”

The German author of that book, Michael Ende, lived through both the first Allied bombing raid of Munich and the 1943 bombing of Hamburg. He saw the most technologically advanced nations of the day wash the world in flame, and I suspect that bled into The Neverending Story, which features an artificial intelligence of sorts, a magical algorithm called AURYN.

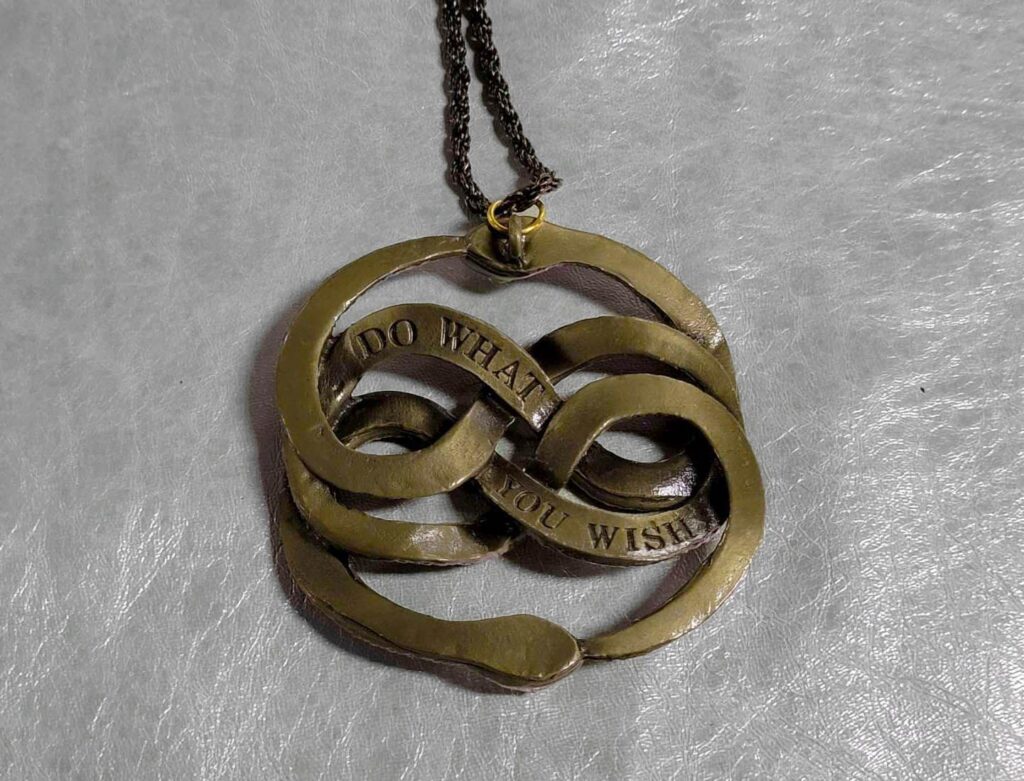

AURYN is an amulet given to the protagonist, Bastian, by the Childlike Empress, the ruler of Fantastica, a vast and mystical realm into which Bastian is thrust. The face of the amulet bears the two snakes, one light and the other dark, devouring each other for eternity. The reverse is inscribed with four words: “Do What You Wish.” AURYN makes real whatever the user wishes. With its power, Bastian remakes Fantastica, accomplishing great and terrible things. But each wish comes at the cost of his memory. By the end, Bastian is reduced to a boy who cannot even recall his own name. He is left groping in the fog that has befallen his mind, struggling to remember himself and his father.

I’m not saying that using technology will reduce you to a husk. But it seems obvious that the pursuit of convenience threatens to leave us purposeless, drowned in digital swarms that chip away at what makes us human. What, then, can be done?

William S. Lind has written in these pages about “Retroculture.” The concept is straightforward: live against the times as families, friends, and individuals. “Those who want to live Retro lives will of course work to remove the conditioning mechanisms from their homes,” Lind wrote. “This means getting rid of most if not all video-screen devices.”

Lind’s solution seems maybe too obvious, too cute, and too easy. But it is also much easier said than done. Try going a day without looking at a screen or using an app. Depending on your line of work, it’s nearly impossible.

But the goal is simply to reduce how much technology is in our lives and how much we depend on it to do what we can do for ourselves. Retroculture, in fact, has surged in recent years. The New York Times reported in 2022 about teens who are ditching social media and technology by switching from smart phones to flip phones and “dumb phones.” A dozen of them meet weekly in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park under the banner of the Luddite Club. The Times joined them for a gathering:

Some drew in sketchbooks. Others painted with a watercolor kit. One of them closed their eyes to listen to the wind. Many read intently—the books in their satchels included Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Art Spiegelman’s Maus II,” and The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius. The club members cite libertine writers like Hunter S. Thompson and Jack Kerouac as heroes, and they have a fondness for works condemning technology, like “Player Piano” by Kurt Vonnegut.

Suddenly retroculture just sounds like culture; that is, the cultivation of meaning, a thing from which we increasingly are cut off despite—or because of—the march of technological progress. People like Bryan Johnson see this problem very clearly, but they look at it in a very different way.

Johnson is a 46-year-old tech entrepreneur who has spent enormous amounts of money to reverse the aging process in an effort to live for as long as possible. He pays $25,000 per gene therapy treatment and swaps blood with his son to stay young.

Johnson believes that people like him, who he declares “Gen Zero,” are in a position to leverage technology and leave humanity behind. He told “The Rich Roll Podcast” that Gen Zero

is a group of multiethnic, multinational people who rise up, and they say, ‘We are willing to courageously step into the future, and we’re willing to divorce or open to divorce from ourselves all human norms, all human customs, all human thought, and we’re willing to say, ‘We’re wide open about everything,’ absolute blank slate.

You won’t be surprised to learn that Johnson also thinks AI should control your life. He already lets it run his techno-medical wellness regime. “It’s easier for me to do this protocol than it is to use my mind,” he explained at a summit last summer.

Johnson deserves credit for his honesty because he is telling us where things are going if people don’t resist, if they trade convenience for their humanity and surrender to those four words: “Do What You

Wish.” ◆

Leave a Reply