America needs to accommodate its cultural and political differences through renewed federalism, while recovering old ways of living.

Since the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the lives of most peoples around the world have been built around the state. Originating in Europe, the state as an institution gradually spread until in the 20th century it attained a near monopoly on its subjects’ primary loyalty. Now, in the 21st century, it is losing that monopoly, as people transfer their primary loyalty away from the state to many other things: to tribes and races, to religions and ideologies, or to business ventures, legal and illegal. Many of these new primary loyalties are also old ones; they were the loci of peoples’ lives before the rise of the state.

What this means for us today is a near-universal crisis of the legitimacy of the state, though one that varies in intensity from one state to another. Since, as our old friend Thomas Hobbes reminds us, we depend upon the state to supply order, and since conservatives’ first principle is the need for order, the crisis of the state may be a daunting problem.

It is important to understand why the state now faces a crisis of legitimacy. Three factors are at work: first, the state is failing to perform its functions; second, it has become captive to a “new class” that lives off the state at the expense of people poorer than itself; and third, at least in Western countries, the powers of the state are being employed to force a hostile, evil ideology—which I call cultural Marxism—down the throats of its citizens.

It is useful to consider each of these factors in turn. As the Israeli military historian Martin van Creveld writes in The Rise and Decline of the State, the state arose for only one purpose: to establish and maintain order, that is, safety of persons and property. After the fall of Europe’s highly successful medieval feudal order, due largely to the Black Death, the continent was plunged into several centuries of disorder (here the best book on the period is Barbara Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century). Europe’s countryside was dominated by wandering bands of men who hired themselves out as soldiers and took whatever they wanted from anyone too weak to resist.

Because the first need of human beings is safety, the Europeans of the time rallied to whoever could best provide it. That turned out to be kings, who in their quest for money and power helped fashion the state. Their subjects generally welcomed the resulting peace and order, and Hobbes’ political philosophy, outlined in Leviathan, justified the new political entity in doing what it needed to maintain the public well-being. In time, the state took on other responsibilities, most recently the assurance of economic prosperity.

For a while, the arrangement seemed to work, but it no longer does. A growing number of states are not performing the functions their citizens expect them to, from picking up the garbage, to keeping the streets safe. High inflation rates also reveal that they are faltering in performing the magic trick of centralized banking, in which debt piles up but never comes due. We need not cast our eyes abroad to see the state’s failure; just look at what happens in America’s major cities after nightfall. States that demand huge tax revenue but deliver poor or no services, including the basic function of maintaining peace and order, lose their legitimacy.

But the current class of elites suffers little from this because it controls the state, lives off the state, and uses the state’s vast revenue and power to exempt itself from the consequences of system failure. Street crime out of control? Just hire private security. Cultural Marxist education ruining the public schools? Send them to expensive private schools. A populist political outsider like Donald Trump manages to grab the brass rings of power? Bend every power of the state to destroy him. This new class of elites cares only about one thing: maintaining its hold on the state. But the public may figure out what is happening and cease to regard the state as legitimate.

In the West, the oligarchies composed of this new elite class have not been satisfied merely with sucking their countries dry to enrich and empower themselves. Like mosquitos, they pump in a poison as they suck the lifeblood of society: the ideology of cultural Marxism, also known under a variety of ever-changing names, such as political correctness, multiculturalism, and wokeness.

Cultural Marxism, which originated with the Frankfurt School in interwar Germany, parallels the old economic Marxism in declaring that certain people are a priori good and others bad, with the two groups defined as “victims” and “oppressors,” respectively. In the old Marxism, workers and peasants were good and members of the bourgeoisie and the owners of capital were bad. In the new cultural Marxism, blacks, gays, feminists, the homeless, et cetera are good, and straight white men and traditional women are bad. Both forms of Marxism seek to dispossess the designated oppressors and to transfer the assets they’ve earned through merit, including such things as jobs and university admissions, to the designated victims.

In neither form of Marxism does it matter what individuals actually do; everyone’s position is ideologically fixed. Thus Senator Edward Kennedy, one of the most notorious womanizers in the U.S. Senate, who brought about the negligent homicide of a woman, remained for cultural Marxists a feminist hero.

In America, the assault by cultural Marxism on traditional Western, Judeo-Christian culture has split the country into two mutually hostile camps. One is made up of the elite; embraces cultural Marxism, either from conviction or out of moral cowardice; and mostly resides in coastal regions. The other camp is the heartland culture, which holds to traditional Western values, beliefs, and ways of living. The former is determined to exterminate the latter, while the latter is trying to defend itself from the former. Since the coastal culture largely controls the state—one cannot be a member of the new elite class if one defies cultural Marxism—the heartland culture increasingly regards the American state as illegitimate.

The immediate question facing the country is whether this cultural civil war will be fought out politically or violently. The longer-range question is whether the heartland culture, which works, will win. If it doesn’t, the United States will become another Third World country, a place where nothing works. That transformation is painfully evident in many places where the coastal culture rules; if you plan to visit San Francisco, take your steel-toed galoshes.

Because the first conservative principle is the need for order, no conservative can welcome civil war (or, for the most part, any other kind of war). So, conservatives’ objective needs to be finding a way to contain Americans’ cultural differences within the political system. There is a way to do that thanks to the wisdom of our Founding Fathers. It’s called federalism—specifically, federalism as it was understood between the ratification of the Constitution and the Civil War.

In those years there was no expectation that life in, for example, Massachusetts would be the same as life in South Carolina, let alone that the federal government had the extra-constitutional power to make it so. Had anyone suggested such a thing, the Constitution would never have been ratified. (Given how events have since played out, the anti-Federalists may have had a point.) By returning to that earlier understanding of federalism, we can accommodate our cultural differences by having leftist states and rightist states. Those who do not like the culture of the state they are in can move. Over time, that will create a contest to see which society performs better, the coastal culture or the heartland culture. Conservatives know which will win.

How can we bring about such an accommodation, one that keeps our differences within the political sphere rather than unleashing violence and coercion? I propose a two-part constitutional amendment. The first part would repeal all amendments after the Thirteenth, which abolished slavery. The second would revise the Commerce Clause of the Constitution, which gives Congress the authority to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian tribes.” The phrase “among the several States” would be stricken.

In addition to allowing states to reflect very different cultures, such an amendment, which eliminates the income tax, would disestablish America’s deep state and reshape our military’s focus toward defense rather than invading other countries. Even some people on the left may find that prospect appealing.

What is our country’s future if we do not return to federalism as a way of accommodating our cultural differences? Perhaps civil strife in a new form, what I call Fourth Generation War.

Fourth Generation War is fought by entities other than states. Examples of Fourth Generation warfighters include the Taliban, Hezbollah, the Islamic State, and the Mexican and Central American drug cartels. Mass immigration is also a Fourth-Generation-War phenomenon, and invasion by immigration can be more dangerous than invasion by a foreign army, because a foreign army eventually goes home.

Fourth Generation War is in one way a reversion to the time before the Peace of Westphalia, because the state loses its monopoly on force. The result is what we have seen when other states have collapsed, such as in Syria, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, et alia. As in 14th-century Europe, it is war with many different parties fighting for many different purposes. The main casualty is order, because where there is no state, sources of order are few and transitory. According to Hobbes, life in such places is nasty, brutish, and short. My novel, Victoria, imagines what life in the United States would be like under these circumstances.

What this means for conservatives is that we must work to uphold and strengthen the state, because the state is the best guarantor of order. That in turn requires us to work to strengthen the state’s legitimacy. The American state’s legitimacy depends, first and foremost, on widespread faith in the probity of elections. Recent presidential elections have shaken that faith, with good reason. The essential problem is that once voting is made electronic, it is susceptible to covert manipulation, just like everything else that is electronic. Done well, such electronic “fudging” can be impossible to detect.

There is an easy solution: return all voting in federal elections to paper ballots counted by hand with poll watchers. Yes, election fraud is still possible with paper ballots. But with adequate poll oversight by all parties, it is readily detectable. It was adequately secure for most of American history, despite the frequent disputes by losing candidates. This gave most citizens faith in the electoral process, which is fundamental to the legitimacy of any republic. Some people on the left may be willing to join conservatives in returning to paper ballots if they think they can win under a system of honest vote casting and counting.

The power of the state is too blunt an instrument to resolve cultural differences, and both the left and the right should care enough about the legitimacy of the American state to avoid using it to oppress their opposition.

Beyond ensuring the honesty of elections, buttressing the American state’s legitimacy means left and right should agree not to push each other too far. At present, the left is doing precisely that by trying to inflict cultural Marxism on the American heartland. A future, triumphant right could also act in a similarly reckless fashion; for example, by passing federal legislation outlawing all abortion or criminalizing homosexual acts. The power of the state is too blunt an instrument to resolve cultural differences, and both the left and the right should care enough about the legitimacy of the American state to avoid using it to oppress their opposition. Returning to true federalism would be a powerful means to restore the legitimacy of the American state while accommodating our cultural differences. It is difficult for a federal government with restricted powers to turn tyrant.

For conservatives, upholding the state is a sine qua non. But is that all we dare hope for? Are we doomed, even with a renewed and strengthened federalism, to see large portions of American society fall into moral decay and social disfunction? If we look only to politics for our national salvation, the answer is yes, lest we spark that widespread Fourth Generation War on American soil, which we must avoid. But there is another way.

One of conservatism’s root ideas is that culture is more powerful than politics. The left seeks to use politics to change culture, ultimately by outlawing cultural conservatism, even if such an effort also risks a descent into Fourth Generation War. But as the left weaponizes politics, we can spread Judeo-Christian culture and its manifestation as traditional middle-class values. How? By pointing out that those values work, and that the instant gratification offered by the cultural Marxists does not.

We are already scoring victories on this front. In cities such as San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle, the social disfunction that cultural Marxism creates alienates even the people who voted for it. The whole state of California is decaying socially, to the point where out-migration in search of public order and institutional effectiveness is swelling. It seems that allowing bums and beggars to take over the streets works better in theory than in practice, especially when the street is your own.

The most revealing votes citizens cast are those they cast with their feet, and no conservative is surprised when people move from disorder to order (the global migration from South to North is another example of this trend). But can we not do more than wait for people to experience the failure of culturally Marxist government and flee from its consequences? Yes, we can.

We can and should build a new national grassroots movement that is chiefly cultural rather than political, and aimed at recovering the middle-class values that were almost universal as recently as the 1950s. I term this movement toward a better past as retroculture.

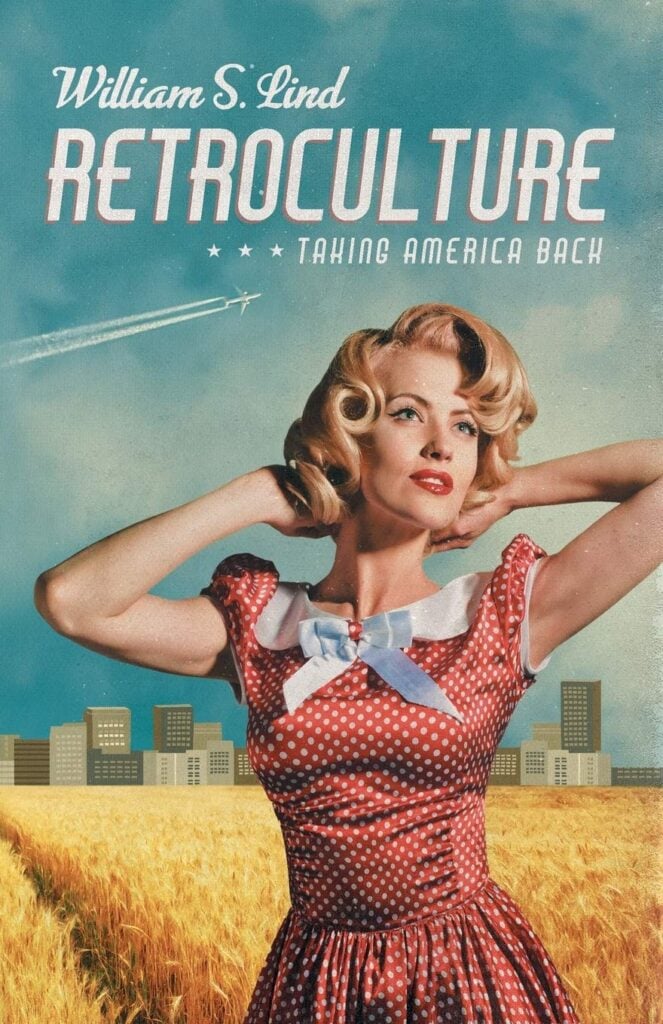

In my book Retroculture: Taking America Back, I offer this definition of retroculture:

Retroculture is a rediscovery of the past and the good things it has to offer. More, it is a recovery of those good things, so that we may enjoy them as our parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents enjoyed them. Retroculture rejects the idea that “You can’t go back.” What we have done before, we can obviously do again. For many years, Americans lived in a land that was safe, solid and comfortable, a civil and even graceful society where life for the overwhelming majority was both pleasant and good. What worked for them can work for us. We can recover the good things they had and knew.

A central idea of retroculture is that everyone can pick the time period they want to embody in their own life and the degree to which they want to go retro. In terms of what periods people can choose for themselves, anything up to 1960 counts. Early America, the Victorian age, and the 1950s all offer different attractions and different degrees of challenge to live up to. My guess is that most normal people would pick the 1950s, America’s last normal decade.

Back by William S. Lind

(Arktos Media, 2021)

A useful way to think of a retroculture movement is as a broader-based version of the homeschooling movement—many homeschoolers are already retro, at least in the kind of education they want for their children. It will be bottom-up, entirely voluntary, and nonthreatening, except to the cultural Marxists who seek to outlaw a realistic understanding of our country’s past (they want to outlaw homeschooling, too). Retroculure is already being practiced by a few individuals and families. As it spreads, retroculturists will form larger groups for mutual support. Eventually, retroculture neighborhoods, towns, and suburbs may form.

A spreading retroculture movement will develop a political dimension, not with the aim of imposing retroculture on the unwilling, but to prevent the cultural Marxists from using the state to suppress retroculture. They will surely attempt to do this, because an America that works the way it used to would be the worst nightmare of the cultural Marxists. Who will sign up for their agenda of cultural pessimism in a country where things are again going right?

The prospect of a widespread, grassroots retroculture movement offers Americans something now in short supply: hope. The future need not be Fourth Generation War, cultural Marxist tyranny, or a high-tech dystopia. If we accommodate our current cultural and political differences through a renewed federalism, while building a movement to recover old ways of thinking, believing, and living—ways that worked—we can give America a bright future. What worked for our ancestors can work for us, as well, if we think and do as they thought and did. Carpe diem.

Leave a Reply