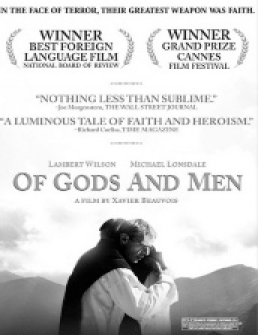

Of Gods and Men

Produced by Why Not Productions and Armada Films

Directed and written by Xavier Beauvois

Distributed by Sony Pictures Classics

Director Xavier Beauvois’s Of Gods and Men quietly, one might say austerely, meditates on the faith and courage of nine French Trappists who faced death at the hands of Muslim fanatics in Algeria 15 years ago. The film is poignant, stirring, and—unfortunately—incomplete. For whatever reason, Beauvois chose to ignore some facets of the case that, in my opinion, should have been addressed.

In 1996, members of the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) abducted seven monks from the Tibhirine monastery at the foot of the Atlas Mountains in Algeria. (Two managed to hide from the Muslims.) Two months later, according to the official story, authorities discovered the monks—or, rather, their decapitated heads. Another Islamic outrage, or so it appeared. In truth, the matter is a good deal more complicated. Perhaps to preserve narrative clarity, Beauvois has passed over this matter, but evidence indicates that responsibility for the outrage may have belonged as much to the Algerian government as to the Muslim terrorists. The Algerian Department of Intelligence and Security (DIS) had infiltrated the GIA so thoroughly that one of its double agents, Djamel Zitouni, had taken charge of a faction within the group. By some accounts, Zitouni’s mission involved instigating his faction to take violent action, killing foreigners as well as massacring entire Algerian villages unsympathetic to Islamic fundamentalism. The DIS wanted the GIA discredited in the eyes of the Muslim population and cared little how much blood was spilled to achieve this end. The plan was to have the GIA’s terrorist tactics license the Algerian army to launch a devastating attack on the organization without stirring up undue resentment among average Algerians. There is reason to believe this campaign led Zitouni to arrange for the abduction of the monks with the intention of calling in the army to rescue them afterward.

The procurator general of the Cistercian order in Rome, Fr. Armand Veilleuxs, accepts this theory. He thinks that Zitouni’s plan had gone catastrophically awry. His faction of insurrectionists either killed the monks themselves or government forces did while trying to rescue them. If the latter is true, it would explain why the authorities claimed to find only the monks’ heads. The Algerian soldiers would have used machine guns to conduct their misbegotten rescue effort, leaving the monks’ bodies too mutilated for display, lest they advertise the army’s role in what became a horribly botched undercover operation.

Father Veilleuxs believes that the government’s foolish scheme was mounted because officials found the monks to be an embarrassment. Algeria had been locked in a guerilla war with Islamic fundamentalists since Algerian officials had shut down a national election in 1992 rather than allow an Islamist to gain office. They naturally assumed the prior of Tibhirine, Dom Christian de Chergé, questioned their tactics, for he was an Islamic scholar who spoke Arabic and was on friendly terms with local imams. They wanted him and his monks to leave the country almost as much as they wanted to quash the guerilla movement.

Depending on whom you believe, the monks were the victims either of Muslim intolerance or of government machinations—or, quite probably, both.

Beauvois has ignored these speculations. This, I think, is a mistake, especially given Dom Christian’s determination to foster understanding between Christians and Muslims. Having been a French lieutenant during the Algerian civil war, he was a passionate proponent of reconciliation. Beauvois should have honored this in his script rather than leaving the matter obscure. Whether naive or not, De Chergé had made progress with his cause, as witnessed by the evident esteem in which his Muslim neighbors held him. I think he would have wanted these people to know that Muslim authorities were exploiting Islamic fanaticism to consolidate their own power.

But we must address the film Beauvois has made rather than the one we might wish he had made. As played by Lambert Wilson, Dom Christian gives every evidence of his faith in Christ and his commitment to recognizing Christ in others. We first meet him attending services at the local mosque with his brother monk, Luc (Michael Lonsdale), joining the congregants in responding to the imam’s reading of the salat. The Muslims around him display no surprise. It’s evident that the monks have joined them before.

Later we watch Luc conversing with a Muslim girl of 18 or so who works at the monastery. She wants to know how you can tell if you’re in love. Luc tells her that she will feel unmistakably illumined from within. She ponders this and then asks how a celibate can be so sure. Luc smiles and confesses that he had been in love more than once in his youth. Then why didn’t he marry? Well, he explains, another love came along, the one to which he’s devoted his life. The girl considers this and then reveals her problem. Her father wants her to marry a man who has not occasioned the illumination of which Luc speaks. “Ah, that is a problem,” the monk sighs and says no more. This moment is both touching and an example of the monks’ evangelistic tact. Luc doesn’t aspire to convert the girl, which would put her in the gravest danger. Like Christian, he conceives his mission to be one of bearing witness publicly and otherwise helping his neighbors as he can.

The monks are men woven into the Muslim community as friends and confidants. So we’re not surprised when the local imam visits the monastery to tell Christian that Islamic extremists have been terrorizing the villagers. In one incident, they stabbed a girl to death just because she wasn’t wearing a hijab. The imam suggests that these men claim to be enforcing Islamic discipline but know nothing of their religion. They don’t even read the Koran, he adds contemptuously. Christian listens quietly, keeping his own counsel. Later, the monks learn of village massacres and the killing of Croatian workers for no better reason than that they were foreigners. It’s clear that the terrorists are closing in and the monks will have to decide what to do. Christian and Luc are firm: They should stay. The others have their doubts. They warn against collaborating in their own martyrdom. They might be motivated by spiritual pride. Others counter that their small community has a responsibility not to abandon their neighbors who have been appealing to them for counsel, support, and consolation as well as the medical care Luc provides.

It takes the monks what seems months to come to an accord: They will abide. Afterward, they share a meal that not accidentally recalls the Last Supper. While they break bread and drink wine, Luc slips a cassette into their refectory’s tape player and the lush chords of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake fill the room. The camera comes in for close-ups of the monks. Each smiles, bemused by Luc’s choice. The famous ballet is a tale of commitment born of love. It tells of Prince Siegfried falling for a girl who has been put under a sorcerer’s spell. By night, she is a beautiful young woman; by day, she’s forced to live as a swan. Only the pledge of true love can dispel her evil enchantment. By playing the ballet, it would seem Luc is reminding his brothers that they themselves had been suffering under an evil spell: the spell of fear. Now they have been transformed. In prayer before their dinner, Dom Christian had invoked “the deep mystery of the Incarnation,” and it’s clearly this that has emboldened them to become what they always hoped to be: fully Christ’s followers in the face of every peril.

In the pre-dawn hours one morning some weeks later, peril arrives in the guise of Muslim guerillas who pound on the monks’ doors and hustle them away. What are the transformed monks thinking? Beauvois provides an answer by having Wilson read in voice-over from the letter Dom Christian wrote three years earlier. Having foreseen the likely imminence of his death, he wanted his family, friends, and others to have his final thoughts. Here are some excerpts.

If it should happen one day—and it could be today—that I become a victim of the terrorism which now seems ready to engulf all the foreigners living in Algeria, I would like my community, my Church, my family, to remember that my life was GIVEN to God and to this country. I ask them to accept that the Sole Master of all life was not a stranger to this brutal departure. I ask them to pray for me. . . . I ask them to be able to link this death with the many other deaths which were just as violent, but forgotten through indifference and anonymity. . . .

I have lived long enough to know that I am an accomplice in the evil which seems, alas, to prevail in the world. . . . I should like, when the time comes, to have the moment of lucidity which would allow me to beg forgiveness of God and of my fellow human beings, and at the same time to forgive with all my heart the one who would strike me down . . . the friend of my final moment, who would not be aware of what [he was] doing . . . in whom I see the face of God. And may we find each other, happy good thieves, in Paradise, if it pleases God.

As I write this on Easter evening, I know, despite Christ’s example, I’ve never loved my enemy, not really. It requires profound faith to recognize Christ in your mortal enemy. Christian de Chergé had such faith; I haven’t, more’s the pity.

Leave a Reply