The Descendants

Produced by Ad Hominem Enterprises

Written and directed by Alexander Payne

Distributed by Fox Searchlight Pictures

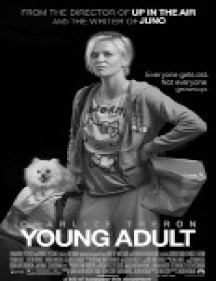

Young Adult

Produced and Distributed by Paramount Pictures

Directed by Jason Reitman

Screenplay by Diablo Cody (Brooke M. Busey)

The Descendants and Young Adult are dark satiric comedies that insist on an unpopular thesis: Sexual misbehavior between even the most consenting of adults can have devastating consequences. They both examine this fraught precinct of the human comedy through the lens of property rights, suggesting that sexual relations can and do provoke nagging ownership claims.

In Alexander Payne’s subtly invasive Descendants we meet Matt King (George Clooney), a Hawaiian descended from an 1860 marriage between an island princess and a Protestant missionary. Matt and his many cousins are the beneficiaries of that union, the princess having come with a dowry of 25,000 acres of virgin Hawaiian real estate with an estimated worth upward of a half-billion dollars. An enviable position to be in, one would suppose, but not without its burdens, especially now that the Hawaiian law of nonperpetuity stalks the family. They must dispose of their joint property by sale or land grant, or the state will take it away in seven years.

Matt is a busy lawyer who believes his wealth entails responsibilities. As he explains, he wants to leave his two daughters enough so they can “do something, but not enough so they can do nothing.” His wife, however, has upended his custodial prudence with her imprudent thrill seeking. Thanks to a speedboat accident, she’s now in a local hospital on life support. Furthermore, it turns out that her thrill seeking went beyond reckless speeding: It impelled her to carry on an affair with a real-estate salesman, a fact the oblivious Matt belatedly learns from his bratty 17-year-old daughter. What makes matters worse is that this Lothario pursued Elizabeth not only for herself but for her connection to Matt’s property. He hoped to become its principal realtor.

The narrative pursues two tracks. Matt must negotiate a decision regarding the disposal of his family’s land and come to terms with his comatose wife. As it unfolds, the story forcibly reminds us that marriage is a contract in which the parties stake ownership claims on each other. But can we own another person? Matt is wise enough to know ownership is, at best, an odd concept. He wonders, for instance, in what way he can be said to own those 25,000 acres. After all, they preceded his existence by hundreds of millions of years. Why should he have the right of disposal over them? And what about his wife? Does his marriage contractually grant him ownership over her? Certainly, she assumed obligations to him when she married, obligations she has grievously violated, but then again, she is her own person, one he seems not to have understood very well. It’s not that he’s been a bad husband—just a busy, distracted one. He mentions at the film’s beginning that it has been 15 years since he’s been on a surfboard. Elizabeth seems to have been rarely off boards and boats. Was he negligent of his contractual obligation to share her interests? His father-in-law thinks so. He angrily points out that, had Matt given his daughter a speedboat of her own with state-of-the-art safety features, she might not have had an accident. She was always an adventurous thrill seeker, he ruminates. And then he levels the emotional coup de grâce: Would she have pursued thrills so compulsively if Matt had been different? “Maybe you should have provided more thrills at home,” he says accusingly. Ouch. Although he knows nothing of his daughter’s infidelity, he may have divined its cause nevertheless. His remark may be what motivates Matt to hunt down his rival in love and real estate. Their meeting takes place with his older daughter in tow. It’s not what you would call cathartic, but it’s memorably awkward. Matthew Lillard plays the lover, and his fearful eyes and frozen smile when Matt confronts him should serve to deter anyone tempted to marital transgression.

This quietly brilliant film has many wonderfully executed scenes, but two stand out. In the hospital, Elizabeth’s friend applies makeup to her unresponsive face. Given what we’ve learned, it’s difficult not to think of Hamlet’s grim graveyard joke at women’s expense as he examines Yorick’s skull: “Let her paint an inch thick, to this favour she must come.” Later, Matt confronts this friend for having known of Elizabeth’s betrayal and kept her silence. “You were probably egging her on, putting a little drama in your life at no risk,” he rails. He will have to strip several layers of cosmetics to come to the mortal truth of all that really matters.

In Young Adult, Mavis Geary (Charlize Theron) also goes in for cosmetics, as well as manicures, pedicures, facials, and wigs. They’re her inch-thick disguises adopted to achieve her quest for a little property reclamation.

Mavis is a beautiful, accomplished, and free-spirited divorcée. She’s got a high-rise apartment in the big city, Minneapolis, a far cry from her small-town upbringing. At 37, her blond shapeliness keeps the men looking. And what ambitious woman wouldn’t envy her professional success as the author—make that ghostwriter—of a series of popular (well, once popular) young-adult novels featuring a person very much like herself at 17? Sounds neat. But she’s received an e-mail informing her that her stay-behind high-school sweetheart Buddy (Patrick Wilson) and his wife have just had their first baby. No more Ms. Happy Success. She packs her Mini Cooper and drives to Mercury, her misnamed slow-mo hometown, where she airily tells anyone who’s curious that she’s come back to see to a “real-estate thing.” She fails to mention that the real estate is Buddy, and she means to renew her claim on him.

Of course, it’s not only Buddy she wants to reclaim. She wants her glory days back, when she was her high school’s prom queen. Everyone loved or, maybe better, envied her.

Her lease on beauty’s magic is now running out, its term being shortened nightly by her prodigious bourbon consumption. If she can reconnect with Buddy, won’t that prove she still has it?

Before her rendezvous with Buddy, she meets another old classmate, Matt (Patton Oswalt), in a bar. He’s the celebrated “hate crime” victim. Some drunken jocks thought it would be a good idea to teach him a lesson when he was 16 and beat his homosexuality out of him with a car jack. The lesson was a permanent one. He’s crippled, wears leg braces, and walks with a cane. To add insult to injury, he also discovered that celebrity is short-lived. When the media found out he was certifiably heterosexual, they lost all interest in him. He now lives in his sister’s home, where he distills bourbon in the garage and collects action figures.

The friendship that blooms between Mavis and Matt seems unlikely at first, but it soon becomes obvious that screenplay writer Diablo Cody is deploying a bit of symbolism. Matt’s damaged body is the physical analog of Mavis’s crippled personality. Adolescence maimed them both, only Mavis doesn’t know it yet.

Matt fears Mavis will make a fool of herself or, worse, break up Buddy’s marriage. She insists that she’s not a homewrecker. She is merely trying to liberate Buddy. When Matt points out that Buddy has a life, she retorts, “No, he has a baby, and babies are boring.”

Finally fed up with Matt’s caution, Mavis turns on him, upbraiding him for dwelling in the past. “You’re leaning on a crutch,” she tells him, blind to the grotesque sardonicism of her words.

But this is Mavis. She’s so self-absorbed that she reads her own thoughts and feelings into other people’s minds. She is absolutely sure that she knows Buddy’s mind. He wants what she wants: to run away together.

If this were all there was to the film, it would stand as a well-made dark satire. But there’s more, and it’s unnerving.

In the denouement, Cody gives the narrative a sudden shake, and, as if it were a kaleidoscope, its pattern changes. The shards of colored glass at the bottom of the tube reassemble to reveal what we hadn’t seen before. At least I didn’t see it; I suspect many women will. Mavis’s behavior suddenly becomes more explicable, and so does Buddy’s. She’s still a monster, but not quite the one we’d been led to believe. She’s also a victim. The revelation is harrowing to behold. Cody and director Jason Reitman break good narrative rules to pound it in. But this didn’t bother me. The story clearly comes from experience lodged deep in Cody’s mind, so to hell with narrative niceties. The ending is at once satirically dark and painfully raw.

By using the plot device of Mavis’s self-referential young-adult novels, the film implicitly attacks industries that capitalize on the dreams and fears of adolescent women preparing to find a mate who will stand by them from romance to motherhood. I know several young and not-so-young women whose lives have come to grief because of this commercial mischief.

Our high schools used to try to inoculate youngsters against romantic excess. One reliable antidote was Alexander Pope’s Rape of the Lock. Of course, this prescription has disappeared from the curriculum in favor of socially responsible texts on how to have safe sex and maintain self-esteem. Pity. Pope’s analysis of female sensibility is exact and perennially relevant. In his mock epic of Belinda’s superficiality, he at once honors the charm of frivolous femininity and warns against prolonging it beyond its useful male-besotting term.

Knowingly or not, Cody and Reitman have taken up Pope’s theme. They handle it far more harshly and, alas, clumsily than did the master of the heroic couplet, but at least they have brought it to the fore once again. I recommend this film to everyone, but especially to young adult women. They might not enjoy it altogether, but they’ll definitely profit from it.

Leave a Reply