I turned forty-one this year. I left a psychological plateau (a crisis would have been way more exciting) and a legal career behind. I suppose an alcohol-fueled bender or an illicit affair broadcast on social media would be what most “folks” (as Barack Obama says) my age might do nowadays, but I opted for sobriety and marital fidelity. And a medieval conference. Before you congratulate yourself on how low your life has not got, hear me out. I wanted to know what I’ve been missing.

In my youth, I took degrees in history and philosophy, criminal justice, and law—areas of study that went through the Middle Ages on the way to becoming the grown-up disciplines they are today on the campus of Political Correctness University. I was not the sharpest knife in the set, but I knew a chronological leap when I saw one. At my undergraduate university, I was baffled by the omission of medieval philosophy from the course offerings. It seemed to me that if one were to go directly from ancient to modern philosophy, one would miss a large part of the conversation. When I approached the department chair with the problem, she was incredulous. Not, of course, about the obvious error, but that I cared. She said, “Why would you want to take that?” I responded that I thought Aquinas was “kinda important.” She laughed. Seriously. A couple more semesters of Alinskyesque agitation by me and a few other brave and existentially troubled souls and we had our class. I decided right then that if I was ever going to learn anything medieval, I would have to find teachers elsewhere. So I did what I’ve always done.

I read.

Except this year, since time and resources permitted, I went to the 51st International Congress on Medieval Studies in Kalamazoo, Michigan. I had never gone to an academic conference before and was, admittedly, a bit naive about, well, everything. I rather expected a kind of Comic Con for medieval scholars—nerdy lords in faux armor and ladies in kirtles and tunics. And while there were a few time-warped individuals wandering around, most of the attendees were scholars, professors, students, and booksellers. But do not be deceived. It was a diverse enough crowd to make half of all university administrators unnecessary. On second thought, given the administrative bloat in higher education these days, maybe that doesn’t quite go far enough, but you get the picture.

Among the earth tones and patchouli, corduroy and tweed, eye-popping tie-dye competed with black clad Goths (not of the Ostro- or Visi- variety), immaculately groomed and slightly affected hipsters in skinny suits, and women with purple hair. The more humbly attired included Trappists, Dominicans, and Benedictines. I even heard one of the monks speculate on a rumor that a Norbertine was roaming around. (The monks and nuns confirmed what I long suspected: They all know one another.)

If English is the lingua franca of the modern world, somebody forgot to tell the organizers of the Congress. So many attendees of different nationalities were present that conversations in the dining hall sounded positively post-Babel. The English spoken—that I heard anyway—was pretty junior high. “So” and “like” seem to be an integral part of the vocabulary of today’s Ph.D., and even crusty old scholars almost exclusively used “amazing” to describe each other’s efforts. One scholar, interestingly enough, was described as “polymathic.” Thinking the woman was some kind of modern Da Vinci, I was disappointed to learn that she earned the appellation because of a career spent working outside her scholarly area but within medieval studies.

The Congress’s sessions were equally diverse. For the more adventurous there was “Picturing Hermaphrodites in Paradise,” and for those with more subdued interests there was “The Rise of Merchant Use of Paper.” Where else can one find important discussions of “Plowing the Medieval Roots of Our Ecocritical Crisis” juxtaposed with “Byzantine Monasticism in Two Anatolian Provinces, ca. 500-700”? I registered early so I could comb the Congress catalog before arrival and choose the sessions I wanted to attend. I suppose every attendee does this. But unlike most attendees, I was not limited to an academic specialty on the point of a pin, so I was able to wander in and out of these weird little worlds. Strangely, at such insular gatherings, where a scholar from New Zealand carries on with a scholar from Russia about the merits of Dr. So-and-So’s argument regarding the translation of some Icelandic text, I was not seen as an impostor or interloper. In fact, I don’t think I was seen at all—a fact that’s quite remarkable given that the “sold-out” sessions had, on average, a dozen or so attendees on familiar terms professionally.

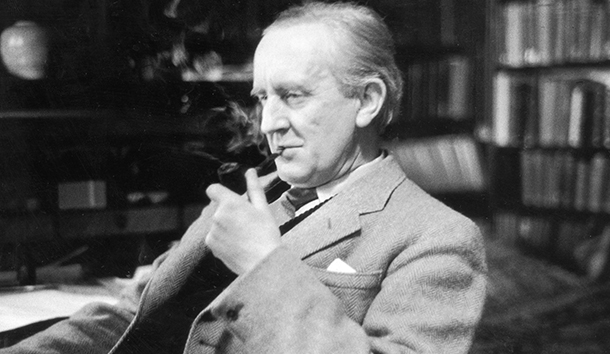

The quality of session presenters was anything but equal. While I oppose university speech codes generally, some of the professors and doctoral students who presented at the Congress ought not be allowed to speak in public. Ever. At a session on Tolkien, one presenter read his entire paper from tiny hand-scrawled scraps in a kind of monotonous mumble. I was horrified—not by the unfortunate man’s violation of every basic rule of public speaking, but rather that the other attendees were so desensitized to Scholarspeak that they sat wide-eyed and gleeful while listening to him. His lecture gave a whole new meaning to drone warfare.

Others, though, were quite good and worth the price of admission. The plenary sessions, it seemed to me, consisted only of scholars with rock-star credentials and quality. In this, the Congress organizers succeeded. University of Leeds scholar Ian Wood gave an excellent paper reappraising the role of religion and the end of the Roman West, with special emphasis on Gibbon. And Jane Chance, of Rice University, gave a worthwhile paper on how J.R.R. Tolkien read Grendel’s Mother. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the plenary sessions were packed, albeit with the notable exception of students who, I discovered later, were sleeping off hangovers and didn’t make appearances until the afternoon sessions.

The Congress, however, was no mere talkfest. I attended a workshop on medieval chess according to Lombard rules. A slower variant of the modern game, Lombard chess makes up in flexibility what it lacks in speed. My admiration for the Lombards was never higher. At another workshop, I built an astrolabe out of cardboard and got a decent grasp on how to use it. Of course, by breakfast the next day, I had forgotten how the thing worked. I fared better at the performances. The Gregorian Institute of Canada performed a 15th-century chant in honor of The Translation of Saint Osmund, the last English saint to be canonized before the Reformation. This was the first time the manuscript was performed since 1457 at Salisbury Cathedral. The Canadian chanters were outdone, in my view, by Corina Martí, a Swiss artist and expert on medieval and Renaissance music. She gave a radiant performance of I dilettosi fiori, 14th-century music for clavicimbalum (an ancestor of the harpsichord) and double flute. When asked how she could possibly find enough air for a double flute, she gracefully responded, “it takes a lot of coffee and cigarettes.”

Neither was the Congress without good old-fashioned barnyard excitement. At one session, a couple of graduate students slapped down a highly regarded scholar of Christian spirituality for an inaccuracy. Later, an aggressive German scholar nearly punched out a food-service employee in the dining hall who dared question his conference credentials. There was also, I learned, a rather rowdy dance which, in keeping with marital fidelity, I did not attend. The truth (I did not tell my wife) was that I could not bear to look.

I cannot say that one Congress on Medieval Studies filled in my knowledge gaps. Nor did going back to the Middle Ages help me go forward in my own middle age. But I will go again next year. These are, I think, my kind of people. And studying medieval culture is vital to a proper understanding and preservation of the West. This may, I confess, be a losing battle. At breakfast one morning, I overheard an exuberant medieval-literature professor telling a lad at a fast-food restaurant in the student union why he should major in medieval studies. “It’s fun,” the professor said, “but the main reason is that you get to read Malory.”

The lad replied, “Awesome, right? Who is Malory?”

Leave a Reply