Even in the beginnings of winter, Georgia’s capitol Tbilisi emits a warmth. One should expect this from a city known for its many hot springs, but the warmth experienced goes much beyond the sulfur baths popular with tourists and locals alike. Tbilisi, with its 1.4 million residents, is inviting in a way that few cities of such a size are. It is very walkable, and a stroll along Rustaveli Avenue, the main thoroughfare, reveals well-dressed men and women roaming with arms interlocked and laughing as they share a reminiscence or news of friends and family.

I originally had no plans to teach in Georgia, and instead was headed to Poland after accepting an assignment through the Center for International Legal Studies to present a short course at a university. The Polish professor responsible for overseeing the visiting professors’ program neglected to have my class approved and this resulted in cancelation of my trip. At the same time, a spot opened at European University in Tbilisi because the scheduled visiting professor was unable to travel due to medical issues. The last-minute change in plans gave me angst, and so I had reluctantly accepted the new assignment to teach Georgian law students the basics of American criminal law.

Upon picking up our bags at the Tbilisi International Airport, my wife and I began to look for the University’s driver who we expected would meet us. To our surprise, we were met instead by the dean of the law school and two other professors, who whisked us off to a traditional Georgian restaurant for a meal and entertainment. According to an old Georgian proverb: “Every guest is a gift from God.” Georgians take this to heart and willingly expend their time and treasure when practicing hospitality.

Georgian food is comfort food, with influences from both the Mediterranean and Persia. Meals are served family style with guests sharing dishes rather than ordering separately. A fixture at a Georgian table is khachapuri, a round bread stuffed with cheese and served warm. A rookie mistake is to gorge on slices of khachapuri and to forget about the bounty to come such as khinkali, the Georgian version of a dumpling, stuffed with meats and spices. My wife’s favorite dish was badrijani nigvzit, roasted strips of eggplant topped with walnut paste. I especially liked lobio, bean soup cooked in a clay pot, and accompanied by mchadi, Georgian corn bread.

The students at European University were impressive and it took very little prodding to get them to open up with questions and to express opinions on the development of both American and European law. Great fodder for discussion was a 2018 decision by their country’s Constitutional Court that struck down administrative punishments for possession of marijuana. The Court based its ruling on Article 16 of the Georgia Constitution, which provides that, “Everyone shall have the freedom to develop their own personality.” I tried to steer discussion away from the public policy issues surrounding drug legalization and toward the issue of who holds the deciding power: judges or parliament.

Some students employed originalist arguments, suggesting that when Georgia’s Constitution of 1995 was adopted no one believed that Article 16 legalized marijuana consumption. Therefore, the Constitutional Court had lurched into the field of legislation rather than providing legitimate interpretation. Others, having read too many opinions by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, thought that it was the judges’ job to expound on Article 16 in the broadest way possible. The standard set by U.S. judicial activism is felt even here, on the opposite side of the globe.

Considering Georgia’s recent history, it’s understandable why some of its students don’t fully appreciate the dangers of judicial policymaking. Georgia was forced to join the Soviet Union in 1922 and regained its independence just 28 years ago in 1991. Independence brought civil war, government by a military council, and rule by former Soviet foreign minister Eduard Shevardnadze, whose regime was awash in corruption. Then came the years of Mikheil Saakashvili’s presidency from 2004 to 2013, which were characterized by economic and governmental reforms coupled with political repression of opponents and protestors. Moreover, in 2008 Russia invaded Georgia in support of the separatist regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, which make up 20 percent of Georgian territory, and Russian troops remain there to this day.

The students, much like the current regime, are pro-Western and hope for a future where Georgia is a NATO and EU member. Were I in their shoes, I would wish for the same thing. With a population of 3.7 million and a land mass just smaller than South Carolina, Georgia has little security against its neighbor to the north. However, from a realpolitik perspective, NATO and the EU would be foolish to embrace Georgian membership inasmuch as this would invite conflict with Russia and not readily advance the interests of those organizations’ current members. For Georgians admission to these clubs is understandably seen as a life preserver in turbulent geopolitical waters.

Considering Georgia’s tumultuous recent history and challenges posed by proximity to Russia, it is amazing that the nation is prospering. The credit must be given to a focus since 2003 on implementing market-based reforms. According to the 2019 Index of Economic Freedom, Georgia ranks number 16 in the world. Reduction in regulations, efforts to stamp out corruption, and a flat tax of 20 percent have led to growth and increased foreign investment.

The younger generation embraces the new Georgia, but among old timers there is a certain wistfulness for Soviet rule, where the government supplied everyone with a job and ensured that the mass of the people enjoyed a roughly equal standard of living. In modern Georgia, there are great opportunities for entrepreneurial activities, but also a rapid fall to the bottom for those without the skills or instincts to survive in a Western-style economy.

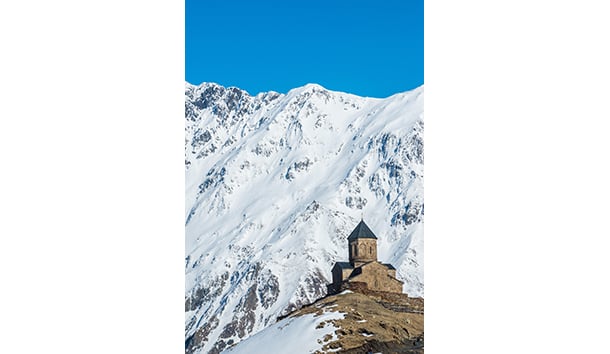

With the country developing a robust market economy, Georgia must be careful to preserve its natural environment. Students and professors took us to see the Kazbegi National Park in the northern part of the country near the Russian border. The rugged beauty of this portion of the Caucasus Mountains is unparalleled. We hiked about two hours to Gergeti Trinity Church, which was built in the 14th century, and sits at an elevation of 7,120 feet. This isolated outpost, with postcard views from all sides, is synonymous with Georgia itself. The church offers a vista of Mount Kazbegi, a glacier-covered wonder that is the third highest in the country.

Tbilisi itself is in an attractive location with the Mtkvari River bisecting the city and mountain ranges surrounding it on three sides. The Old Town features cobblestone streets, 19th century wooden houses painted pastel colors, and plentiful sidewalk cafés where Georgians and their guests enjoy wine.

Winemaking in Georgia is an art that dates back 8,000 years. In fact, evidence of the earliest winemaking in history was found during excavations of Neolithic villages near Tbilisi. Early Georgians transformed grape juice into wine by burying it underground in qvevri, large clay jars coated inside with beeswax. This technique is still used today for a small percentage of Georgian wine. With more than 500 varieties of grapes, a wine connoisseur visiting Georgia is hard-pressed to run out of different tastes to tempt the palate.

Whether imbibing or not, conversations with Georgians reveal a great optimism for the country. Considering the progress made since 1991 and the economic growth, Georgians have good reason to expect even brighter days. From my experience with the students at European University, it seems there is a rising generation quite capable and willing to build on the solid foundation being erected.

While Russia is an obvious danger, Georgians ought not underestimate the more subtle cultural danger of their love affair with the West. A great strength of Georgia is its Orthodox Christianity, which is embraced by 84 percent of the people, and its homogeneous population (87 percent are ethnic Georgians). The secular West has rejected the Faith and mouths platitudes about the diversity as a boon while its leaders applaud Islamic invasion. The West that Georgians seek to imitate will soon be no more, absent courageous measures—and the same could happen to Georgia if it forsakes its sense of kinship and Christian heritage.

Image Credit: 14th-century Gergeti Trinity Church, Stepantsminda, Georgia (Zoltan Bagosi / Alamy Stock Photo)

Leave a Reply