In my new home of Ashland, Ohio, there is a sign that welcomes all comers to “The World Headquarters of Nice People.” It seemed to me as if the entire town conspired to make my move as pleasant as could be. This is “Midwestern Nice” in a nutshell.

But I’ve found the flavor of American hospitality can, like complacency, kill. Too much of it is like a slow poison. It enables when it should proscribe; stays its hand when it ought to punish. It renders good people vulnerable to the fever dreams of ideologues and the schemes of a cynical managerial class.

Desiree Lomax offers a case in point. Lomax landed her first felony conviction in 2011. She lied to police about the whereabouts of Joseph Hampton and provided him with clothing, food, and a vehicle after he shot dead a man in Zanesville, Ohio. For all this, Lomax received the accommodative mercy of probation.

After she violated her probation twice, Lomax was sent to Muskingum Behavioral Health for “treatment.” Rather than turning her life around, however, she used the program to network. In her mind, rehab was the perfect place to find drug buyers, and it was here that she met Kevin “Taylor” Strang. After a relapse, Strang wound up at Muskingum Behavioral Health, making him easy prey for Lomax.

On Aug. 31, 2018, Strang didn’t show up for work. His fiancée, Georgia, called Strang’s parents, who eventually found their son’s lifeless body. Strang had 30 times the lethal dose of fentanyl in his blood.

Lomax not only denied having sold Strang the fentanyl but ever dealing drugs at all. But investigators found messages on her devices that helped them identify 19 individuals as Lomax’s regulars.

Come sentencing time, assistant prosecuting attorney John Litle handed out screenshots of Facebook posts made by Lomax—she had thrown a celebration before departing for prison.

In Lomax’s sentencing memorandum, there is a paragraph that caught my eye because it implicates Ohio’s pitiful former governor, John Kasich.

“The State must elect between corrupting another with drugs, an offense carrying mandatory time and mandatory incarceration but maxing at eight years, and involuntary manslaughter, an offense that carries more potential time,” wrote Litle, “but time which is not-mandatory and therefore can be reduced by up to 20% by the prison systems up front due to John Kasich’s House Bill 86 (2011).”

HB86, Litle’s footnote explained, was designed to award an offender “good time,” thus reducing their sentence, but only when they actively do something to earn it. In practice, however, every offender is given the 20 percent time reduction and, contrary to its very design, must earn “not” getting the reduction. Is this just another case of Midwestern Nice gone wrong? On the administrative level, Litle said the practice of not keeping criminals behind bars often comes down to cold hard cash.

With 15 years of experience prosecuting felony cases in Ohio, Litle knows the game. I asked him if the dissonance between the letter and practice of HB86 is a matter of misguided compassionate policy. He chose his words carefully.

“It’s difficult to ascribe motive to an entire body of hundreds of people,” he said, “but I assure you that there is a significant motive to save money in each one of these bills that they pass.” Litle pointed me to the Reagan Tokes Act, named after Reagan Delaney Tokes.

Tokes, then a 21-year-old student at Ohio State, was abducted by convicted sex offender Brian Golsby while leaving work in downtown Columbus. The last text Tokes sent to her father read, “Dad, I can’t talk right now, but I will call you when I leave tonight.” When she didn’t call, her father knew something was wrong.

Golsby raped Tokes, then forced her to drive to Scioto Grove Metro Park. Amid the bluffs and forested trails, he had her strip naked, marched her out into a field, and shot her in the head twice. Golsby never even bothered to remove his GPS monitor, issued to him by the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction (ODRC) while he lived in state-contracted housing.

The Tokes family sued the ODRC on the grounds that it was negligent for allowing a known predator like Golsby to walk the streets. But a judge dismissed the lawsuit because, according to reporting by the local ABC affiliate, the department “had no special duty to protect Tokes.” The Tokes family should be forgiven for holding fast to the quaint belief that the criminal justice system ought to protect the innocent.

With her death, the Reagan Tokes Act was born, ostensibly conceived to “stiffen up some penalties,” Litle told me. In one respect, it does. The Tokes Act brings back “indefinite sentencing” for some offenses in Ohio. A criminal sentenced to 10 years, for example, could be held for an additional five if he fails to behave himself in prison. All of that certainly sounds nice, Litle said, but bureaucrats were not above tucking in a provision that cut costs for themselves by letting criminals out of jail sooner rather than later.

This component in the Tokes Act allowed prisons to release “anyone up to 15 percent early,” Litle explained, “for whatever they determine to be ‘exceptionally good behavior.’” These “jailbreak provisions,” as Litle called them, are entirely standard on the legislative level. “We ended up fighting that provision, long and hard,” he said.

That fight was fruitful: Prisons now must come to the original judge and receive permission to release a criminal. Litle said he feels confident that the judges in his county will generally do the right thing and reject requests for early release. Elsewhere, he said, that is certainly not the case.

A kind people—and Midwesterners are kind—are naturally vulnerable to the siren song of compassion crooned from the lips of ideologues who provide an elegant mask for managerial negligence. Think tanks, “community organizers,” and academics preach the gospel of the latest sociological studies, which proclaim the doctrine of healing, rather than punishing, the worst and recidivist elements of society. Good-hearted people want to believe this is true, because they want to see the good in everyone—and the cynical managerial regime needs them to.

My conversation with Litle turned to Franklin County, Ohio, where 64 juvenile court probation department employees are set to have their jobs eliminated. The layoffs are part of what The Columbus Dispatch described as a new philosophy in Franklin, “that juveniles fare better and the community stays safer when support is emphasized over incarceration.” Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. Census Bureau, the American Community Survey, and the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting show that Franklin and Muskingum deal with the same socioeconomic conditions. The two have virtually identical rates of child poverty, income inequality, single-parent households, and very similar unemployment rates. Yet Franklin’s violent crime rate is more than twice that of Muskingum’s. Litle chalked it up to philosophy and practice—there are still some people in Muskingum who want to fight crime by punishing criminals.

These “woke” studies and science, though preached by true believers, amount to mere vehicles for managerial avarice. Litle advised me to follow the money, specifically, to a program called RECLAIM.

The state of Ohio conceived RECLAIM 15 years ago as a massive funding grant to its juvenile courts. The giveaway funded probation departments as well, and the money was used to hire probation officers. But the strings attached were eventually revealed. “The state gradually continued to hang requirements on the funding,” Litle said, “to not send people to prison.” The model is simple: provide funding, then pull it if too many people are sent to prison.

“Once they addicted them to the money, and they hired all of the people with all of the money, they then took it away for every person that got sent to the juvenile prison,” Litle said. “In so doing, they successfully shuttered every juvenile prison in the state of Ohio, except for two.” Litle estimated that the juvenile inmate population decreased from approximately 2,700 to less than 500 under RECLAIM. “And that’s not because crime went down,” Litle assured me. A version of RECLAIM for adults appeared in Ohio, officially called “Targeted Community Alternatives to Prison,” or T-CAP. But in “the real world,” as Litle wrote in testimony to the Ohio House of Representatives, “we call it a bribe; a disgusting, dishonorable, and immoral act of paying someone money to refuse to do their job and uphold their oath.”

The schemes and dreams of bureaucrats and ideologues do nothing to actually reduce crime or keep people safe. But what, then, explains apparent statistical reductions in lawbreaking?

Litle said he believes that the cynical practice of not putting and keeping criminals behind bars, along with the philosophy of compassionate “criminal justice reform,” has created an effect that “backfeeds” into the system.

“Cops do not bother filing charges on juveniles, or adults, for that matter, that they know are not going to get any punishment,” Litle said. “[They] will only learn the lesson that the justice system is a joke. It’s actually counterproductive.”

“When cops won’t do anything,” Litle added, “people won’t bother calling the cops, and when no one bothers calling the cops, the entire neighborhood descends into chaos.” What follows is a retreat by law enforcement from areas that need more, not less police presence. Crime, then, has not actually been reduced; there has merely been a reduction in the number of people reporting it. Data from the Bureau of Justice—as I previously wrote in these pages (“The Broken Promise of American Cities,” September 2019)—confirms Litle’s take. Only 45 percent of violent crimes tracked by the bureau were reported to police in 2017. Citizens’ belief that police “would not or could not do anything to help,” was among the top reasons cited.

Caught between criminals, ideologues, and the managerial regime are everyday Midwesterners who find a virtue in “nice.” But laws and social covenants cannot survive against the wolves who bear their fangs at kindness. “Covenants without the sword,” as Thomas Hobbes wrote, “are but words and of no strength to secure a man at all.”

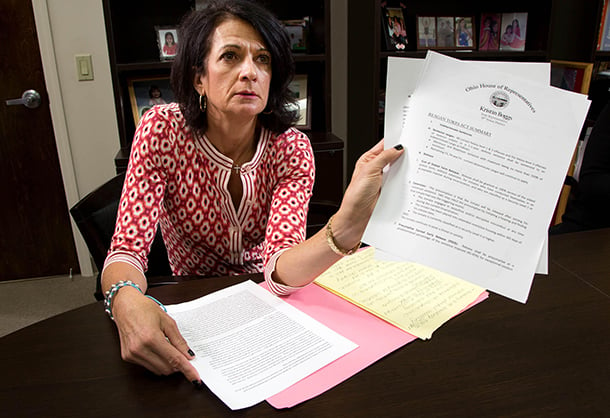

Image Credit:

Lisa Tokes, mother of murdered Ohio State student Reagan Tokes, displays a copy of the Reagan Tokes Act

Leave a Reply