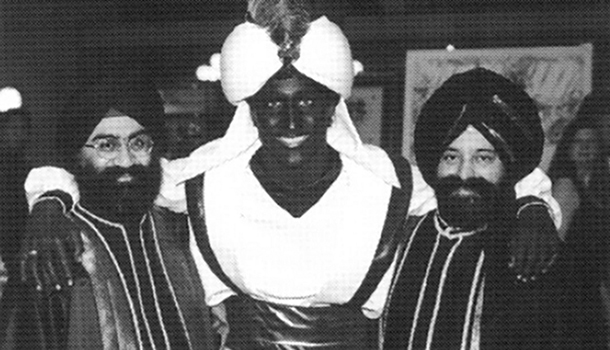

The Canadian federal election in October confirmed a long-term, leftward trend in Canadian politics. Despite Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s blackface scandal, the Liberals retained power, winning a plurality of 157 out of 338 seats and 33.1 percent of the popular vote. Conservatives won 121 seats (34.4 percent of the vote), gaining truly overwhelming support from Western Canada, particularly from the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

While the sovereigntist Bloc Québécois won 32 seats in Quebec (7.7 percent of the country-wide vote), the lynchpin of the Liberal’s retention of power is the New Democratic Party (NDP), Canada’s social democrats, which won 24 seats (and 15.9 percent of the popular vote).

During the last five-and-a-half decades, the Canadian Right has failed to articulate a counter-ethic to the now-dominant Liberal idea of Canada, such that it cannot even defeat a prime minister self-wounded by a multitude of gaffes, corruption scandals, and blackface embarrassments, all of which seemed to have comparatively little impact on the election’s outcome.

Trudeau’s father, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, prime minister for almost the entire period between 1968 and 1984, can claim credit as the architect of the present left-liberal Canada. Pierre Trudeau had been a Communist sympathizer, but ended up becoming an exemplary left-liberal and “cultural Marxist” who thoroughly reshaped Canada according to his political preferences.

The elder Trudeau stressed multiculturalism, high immigration, and bilingualism (in the form of promoting French), policies and emphases that no later Prime Minister, conservative or liberal, has summoned the will to challenge. He seized on the power of his office to effect decisive change in Canadian society. Much of his success was based on the rock-solid support of Quebec, which valued his French ancestry and linguistic ability.

The first signs of the decline of the Canadian Right can be traced back to the 1960s and the battles between Liberal Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson and the staunch Tory John Diefenbaker (Prime Minister from 1957 to 1963). The crucial 1963 election was a conflict between a more traditional vision of Canada represented by Diefenbaker, and the “modernizing” tendencies advocated by Pearson.

Pearson used his electoral victory to introduce the so-called “points” immigration system, which was a step away from the older preference for European immigrants. Canada was the first country to introduce a merit-based points system, in which potential immigrants are awarded an eligibility score based on several selection criteria. Currently, there are six: language skills (British English or French); educational achievement; work experience; age (under 18 and over 47 get zero points); legitimate employment secured before emigrating (in some cases this employment must be deemed in Canada’s national interest); and “adaptability,” which comes down to your prior experience in Canada, and whether you have any relations in the country. The current points system exists in addition to a generous refugee and humanitarian resettlement program, which is not subject to the merit-based criteria.

Pearson also enacted Canada’s first bilingualism policies. His tenure was the beginning of the fundamental overturning of a more traditional Canada, perhaps best symbolized by the adoption of the new flag, dubbed the “Pearson Pennant,” in 1965. The elder Trudeau would expand these “modernizing” tendencies after he won a huge majority in the 1968 federal election. “The Trudeau revolution” engendered the Charter of Rights and Freedoms of 1982, which entrenched multiculturalism as a central Canadian principle, and embraced the idea of government initiatives on behalf of “historically disadvantaged” groups.

The social framework of Canada had been changed so drastically that even after the Progressive Conservative Party won majorities in 1984 and 1988, it ended up mostly implementing such leftist programs as affirmative action, known as “employment equity” in Canada, and passing a strengthened Multiculturalism Act. Conservative Party Prime Minister Brian Mulroney also raised immigration levels to a quarter-million persons a year during this period, after they had actually fallen to 54,000 in Pierre Trudeau’s last year in office (from 1983-1984). The immigration levels were never lowered thereafter below a quarter-million each year. At the present time, the Liberals are upping the ante, promising to accept 350,000 immigrants annually in a country less populous than the U.S. state of California.

The Canadian Right tried to regroup through the creation of the Reform Party in 1987, but the new party faced unrelenting media hostility. Despite the name-calling, they were able to win 52 seats in the 1993 federal election, and 60 seats in 1997.

Part of the Liberal Party’s strategy in the 1990s in trying to appear moderate was to feature its own brand of fiscal conservatism. Liberal austerity measures included not rescinding the Goods and Services Tax, as party leaders had explicitly promised to do, reducing the benefits of the unemployment insurance reforms, and adding to the contributions that had to be paid to the Canada Pension Plan.

Preston Manning, founder of the Reform Party of Canada, tried in 1998 to push back the leftward tide and to “unite the right” in Canada around conservative principles. This effort at party-building culminated in the creation of the Canadian Alliance.

In 2000, Stockwell Day was selected leader of the Canadian Alliance. Although he began well enough, the media pulled out all stops associating his Evangelical faith with Christian fundamentalist extremism. In 2001, Day was brought down by a concerted campaign of vilification by the media, the Liberal Party, and dissidents within his own caucus. The ensuing Canadian Alliance leadership selection process of 2002 fell to a tension-avoiding centrist in the mold of Mulroney: Stephen Harper.

In December 2003 a merger was negotiated between the Canadian Alliance under Harper and the federal Progressive Conservatives under the leadership of Peter MacKay. Significantly, the adjective “progressive” was dropped from the name of the reconstituted Conservative Party. This move came after decades of media assaults on the Canadian right and appeared, at least initially, to show some boldness on the part of its new leadership.

The Liberal government was finally voted down in the federal Parliament, and during the ensuing federal election in January 2006 Harper won enough votes to cobble together a minority government. Harper remained in power with minority control until finally winning his majority in May 2011.

But once it had the majority, the Conservative government simply perpetuated social policies that the opposition had put in place. Among them were same-sex marriage, abortion without restrictions, and high immigration rates from the Third World, through both its refugee and points programs.

In the October 2015 federal election, Justin Trudeau ousted the Conservatives with a strong majority. Among his signature policies was the full legalization of cannabis. His most important pronouncements were his declarations that “Canada is a post-national state” and that there is no “core [Canadian] identity.” In 2019, he was able to retain a strong minority government, but it will probably be largely beholden to the NDP, which is even further to the left than Trudeau’s Liberals. The Conservatives under leader Andrew Scheer notably failed to win the support of Ontario and Atlantic Canada.

There is a nexus of interests which certain American and European critics have called “the managerial-therapeutic regime,” which could be characterized as socially leftist power structure that is favorable to the economic status quo. This structure north of the American border is strengthened by North American popular culture, manufactured by the U.S. media, which is the primary “lived cultural reality” for most Canadians.

The current Canada is devoid of any significant right-of-center cultural presence, lacking a strong military that can channel and promote the male virtues, organized religion as a powerful social force, and parents willing to engage in homeschooling. Unlike the United States, and with the exception of a figure like Tory thinker George Grant, Canada lacks a robust tradition of anti-corporate, ecological, and agrarian dissent.

The only realistic hope for resistance to the towering leftist presence in Canada may be the building up of regionalist alternatives, which still seems possible in Western Canada. The recent federal election reveals a clear regional divide, and there is now talk in Canada of a so-called “Wexit” (Western exit). This tendency has been simmering over decades in the West, which still holds grievances against eastern provinces. The East demonizes the West’s energy industry, and yet gladly accepts federal funds transfer payments siphoned from Western taxpayers. A classic, decades-old bumper sticker phrase, “Let the Eastern Bastards Freeze in the Dark,” can still be seen in some parts of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Quebec separatism also appears to be surging, as shown by the results of the 2019 federal election. Perhaps the only way the country could be made even minimally tolerable to social traditionalists is if massive decentralization occurs. This of course is something that the American Right has also considered for its country.

Image Credit: above: a controversial photo from a 2001 West Point Grey Academy school newsletter featuring current Prime Minister of Canada Justin Trudeau (center)

Leave a Reply