Our foreign-policy editor, Srdja Trifkovic, has posted in Chronicles Online three provocative commentaries in commemoration of Bastille Day: “Reign of Terror,” “Three Classic Critics of the Revolution,” and “The Revolution and Modern France.” I would urge our subscribers to read them. Like Carl Schmitt, Robert Nisbet, Russell Kirk, Alain de Benoist, and others on the American and European right, Trifkovic finds prophetic insight in counterrevolutionary critics of the French Revolution.

Indeed, such critics have relevance for understanding our own age, which is more than two centuries removed from their historic target. Just as the French radicals of that distant age undercut the foundations of their own society, woke America has now gone so far as to strip men and women of their traditional identities. We have gone beyond discarding what Edmund Burke called “the wardrobe of moral imagination”—that is, customary social identities—in obliterating human distinctions. Our state and media now urge us to imagine that organisms who used to be defined as men and women are all “birthing persons,” who can change their genders simply by announcing their new biological preference. Far more than French revolutionaries ever did, American and Western European elites are now insisting on a clean break with their national pasts and seeking to impose alternative visions of reality on their pliable subjects.

The French Revolution foreshadowed developments that have been unfolding in this country since the 1950s. “Problems” that might have been addressed more discreetly became excuses to revolutionize society. We might have listened to Burke, who, in the concluding part of his Reflections on the Revolution in France, offered possible reforms that might have been enacted to deal with certain grievances in French society. The third estate (the commoners and bourgeoisie) could have been given broader representation in political assemblies; servile duties could have been lifted from the peasantry; and broader religious tolerance for non-Catholics (a process that had already begun by the 1780s) could have been easily achieved. Such reforms might have saved the French monarchy from the disastrous effects of an avoidable revolution.

The French quantitative historian Pierre Chaunu published in 1989 a learned work, Le Grand Déclassement, which was produced “by way of commemorating” the storming of the Bastille. According to Chaunu’s rigorous research, the events that followed that storming, the effects of which continued to be felt throughout the Napoleonic wars, bled his country white. Equally significant is that, beginning in 1789, France, despite its larger population and its own industrial revolution, condemned itself to permanent economic inferiority relative to England. Chaunu was a French Protestant and quite willing to live in a republic, but he viewed the revolution and its aftermath at least as critically as European counterrevolutionaries.

One might imagine, counterfactually, an America that had not undergone a social and cultural revolution starting in the 1960s. We would certainly be better off without that never-ending cataclysm, which has destroyed historic liberties, the independence of communities, and gender relations, all in the name of fighting “discrimination” and overcoming “prejudice.” Our revolutionaries, moreover, wield instruments of control that the French revolutionaries could only have dreamt of. Perhaps intoxicated by this power, the American state department is now inflicting gay marriage, transgenderism, and other “human rights” on our client states.

Those who believe this eventuality could have been stymied in 1965, with the civil rights legislation and its enforcement, are like those French reformers who chose to believe their revolution might have ended with the Constitution of 1790, turning France into a parliamentary monarchy. In the French case, the Paris mobs made sure the revolution would eventually turn into a Europe-wide conflagration; in the American case, the expanding power of the media, university radicals, and government agencies would ensure that the civil rights revolution would become ever more sweeping, finally embracing a multitude of other victims beside blacks and women.

It is possible, of course, to wonder what might have been our fate if segregation had been dismantled a bit earlier. Perhaps a milder, less intrusive version of the Voting Rights Act might have lowered demands for more thoroughgoing change. Would that course have halted the rush of later historical events? I really don’t know, but I remain skeptical.

It may give some dreamers pleasure isolating what they like in a complicated process of change, without considering the larger context to which it belongs. But the fact remains: the forces that lead to a major historical development will continue to express themselves well beyond the point at which some might wish the process to stop. Here I agree with the French politician Georges Clemenceau, who observed about a hundred years ago, “la révolution fait un bloc”—the entire revolution is of one piece. This is as true for recent American history as it was for the French Revolution.

A preoccupation with the egalitarian ideal involves not simply a call for equality before the law but for a continuing imperative to completely transform human relations. In the modern era, the demand for democratic equality has carried the seeds of social destruction, because it can never be fully satisfied. It is impossible to keep pushing the ideal without wreaking havoc. The peacemaker will have a hard time convincing others that the hierarchical order of the household—found in Aristotle, the Old Testament, St. Paul, etc.—is really a call for moral equality within the context of natural differences. Nobody, not even fundamentalist preachers, would dare to defend the traditional family structure any longer. Even just claiming that gender differences exist is now tantamount to denying the Holocaust.

This has happened, I would argue, because the idealization of equality as the highest value could not be stopped once it was weaponized against the past. Egalitarians made war on the family and the very idea of gender as being inconsistent with the vision of a perfectly leveled world where all human beings must be continually reinvented to achieve and maintain interchangeability. Sex change operations and the abolition of genders are not a deviation from a noble ideal but the exemplification of society’s highest value in an equality-obsessed era.

Perhaps we should stress the adjective “modern,” because the ancient world had a far more limited notion of our highest good. In ancient Athens, the furthering of equality meant extending government offices to those who paid lower taxes and were engaged in physical work. Back then, equality could also be satisfied by reforming (without abolishing) the tribal nature of voting districts. Reforms like these, carried out by Cleisthenes in 508 and 507 BC, after a period of civil strife, fulfilled the demands for what the Greeks understood as equality.

No one back then suggested extending full citizenship to women, slaves, or foreign residents; the innovations carried out by Cleisthenes represented the limit of what the ancient polis understood as homoiotes (equality) within a framework of popular government. In Aristotle’s Politics, we learn that Pericles gained approval as a popular leader by striking from the voting rolls the names of those with foreign-born parents. Obviously, diversity was not part of the democratic package in that world.

In our own world, much more is demanded in the name of true equality. In fact, we’re not allowed to focus on any other ideal until this one is fully realized. And if our democratic egalitarian idealism creates its own contradictions, we must live with those as well. Thus, we are told by our political and cultural leaders that equality means giving special recognition, including compensatory reparation, to those who suffered “discrimination” in the past. Western societies that imitate our model now happily embrace this teaching, along with our rap music. For them, too, equality has become the highest good, and a bonus awaits those who push it the hardest, for these activists can have themselves declared authorized victims, with the assistance of the obliging media.

Nobody is suggesting (certainly not this writer) that nothing in the past ever had to be reformed or, in some cases, abolished. We certainly recognize that some people have been treated unfairly in the course of Western history—for example, slaves in Athenian mines, non-noble applicants for government positions in pre-revolutionary France, segregated blacks who were once denied the use of public facilities in America. But at least in traditional Western societies, grievances can be and have usually been addressed well short of an egalitarian revolution, a drastic course of action in which momentum cannot be easily halted. In institutions that have been established over generations, cautious change may be all the prudent should ever attempt.

The United States has embarked on a very different course for the last 60 years, while pretending, unconvincingly, that the same constitutional order has been in place since the late 18th century. This facade seems less and less credible as we look at the social wreckage all around us. Unhappily, we are now at that point when the flood can no longer be held back. It will take nothing less than an equally powerful counterforce to restrain this torrent.

—Paul Gottfried

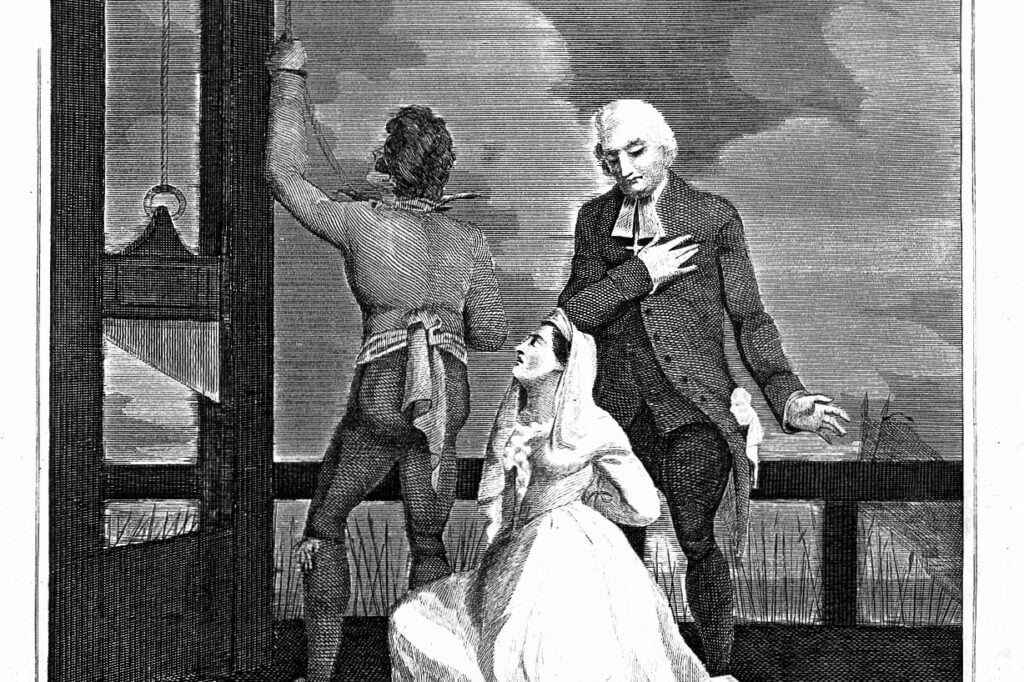

Top Image: Mankind drowns in the flood while the rain keeps pouring down. 13th-century Byzantine mosaic. (Scott Nevins Memorial / via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Leave a Reply