Joshua Tait, who is completing a dissertation on the American conservative movement at the University of North Carolina, is a virtue-signaling expert on his object of study. Never does Tait hold back in judging past conservatives by his super-duper progressive standards. For example, he offers this on one particularly revered conservative icon: “[Russell] Kirk was an idealist and an ideologue, but this was in the context of massive resistance to school integration and the Jim Crow regime enforced by state sponsored violence. He was willfully ignorant of the realities of white supremacy.”

Tait locates pure evil lurking in Kirk’s statement of more than 50 years ago that “the South need feel no shame for its defense of beliefs that were not concocted yesterday.” Tait complains that Kirk dealt “abstractly and unreflectively” with such abominations as the Confederacy and Jim Crow, and that he often expressed high regard for Robert E. Lee as a Christian gentleman—a vice shared by Winston Churchill, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Jimmy Carter, and even Bill Clinton, among many others. Of course, it’s not even clear that Kirk’s comments were defending slavery or segregation—it is entirely possible he was speaking about the folkways of pre-industrial farming communities.

Tait all the same has raised a serious question as our political conversation continues to veer leftward. What do we do with all those conservatives who once clung to positions that we are now supposed to scorn—or as George Will would put it, consider “closed?”

There are two ways of engaging this problem. One is to purge past people and ideas in order to allow the conservative movement to become a force that Joshua Tait can be proud of. When National Review once boasted that the magazine still stands in the tradition of its founders, former Chronicles editor Chilton Williamson retorted that very few, if any, of those founders would be politically correct enough to make an appearance in Rich Lowry’s sanitized magazine. Needless to say, Joshua Tait would have no trouble making the grade.

The second option is to subject to convenient reconstructions those who once held what are now inappropriate views on the Confederacy, feminism, gays, civil rights laws, and/or religion. Kirk has been fortunate enough to be honored with such a posthumous transformation. What I now read about him on establishment conservative websites often bears little if any resemblance to the person I once knew and valued as a friend. Pace some of his recent interpreters, Kirk was not especially well disposed toward the civil rights movement, which he thought would radicalize our electorate and derail our republican constitutional order. Russell was certainly not a racialist (he gave generous refuge in his home to Ethiopians fleeing their communist regime). Nonetheless, he distrusted the government’s leap into social engineering, even in the name of lofty ideals.

Tait is certainly correct that Kirk deeply admired historical and literary figures who fell short of today’s “woke” moral standards. Curiously, I don’t recall anyone from my youth who would have met these fastidious standards, including Marxist professors of mine who didn’t much like gays. By the standards of an earlier age, and not just by the standards of the conservative reaction to the liberalism of the 1950s, we lived in total ignorance of the current mystique of designated victims. Not surprisingly, self-identified conservatives in the middle of the last century were positioned well to the right of where our media conservatives now stand. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I don’t recall self-described gay activists and second-wave feminists (or their equivalent) being featured in National Review or Modern Age in the 1950s or 1960s. W. F. Buckley’s critical view of the Voting Rights Act and Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was the prevalent opinion among NR contributors at the time. I also don’t remember any of these conservatives applauding the politics of Martin Luther King, Jr. Onetime NR editors would be astonished or appalled to learn that King has been reinterpreted as a conservative Christian theologian and a friend of capitalism. Talk about the tricks the living play on the dead!

Tait nonetheless should be complimented for reminding us how little of the past, even the relatively recent past, fits into the intersectional present. This has made it all but impossible to appreciate anything that fails to validate what are now the fashionable claims of victimhood. In fact, honored thinkers of even 30 years ago have been pulled from their pedestals for not quite reaching our present level of required sensitivity.

Since media conservatism tries to remain part of the “public conversation,” it does what it can to accommodate leftist censors. This means turning past heroes into unpersons or reconstructing them in such a way so as not to offend the left. Authorized conservatives who play this game have their work cut out for them, especially if those like Tait, who now writes on conservatism for the Washington Post, become the censors of their movement.

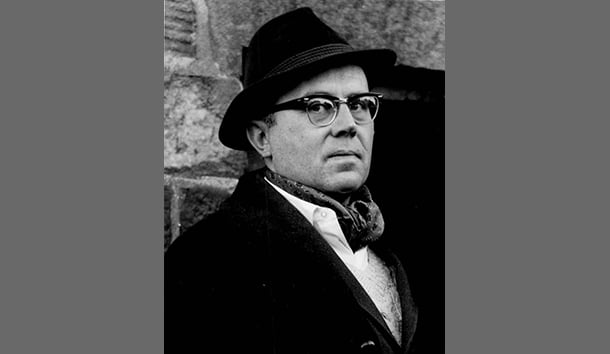

Image Credit: Russell Kirk, 1962 (Wikimedia)

Leave a Reply