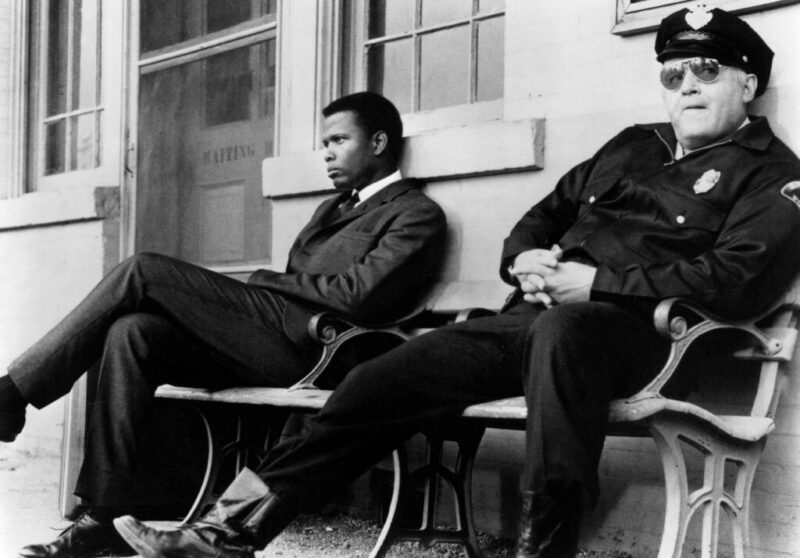

Picture an elegant black teacher given the task of teaching poor white students—students whose national ancestors had embarked on a mission to spread civilization to the part of the world he comes from. This is the theme of To Sir, with Love, a 1967 film featuring the renowned actor, Sidney Poitier, playing the part of Mark Thackeray, a Guianese engineer who comes to London to look for a job. Several unsuccessful attempts to find work in his area of expertise lead Thackeray to apply for a temporary teaching position, which he finds in a high school in London’s East End. The East End is a poor, working-class neighborhood where people do not speak the Queen’s English, and no one takes afternoon tea. It is not a desirable teaching post.

Puzzled by the noise of loud music coming from the classroom, Thackeray learns from his new colleague, Weston, that “they’re probably celebrating their victory” over the old teacher, who has just resigned. “So you’re the new lamb for the slaughter. Or should I say black sheep?” asks Weston, one of those whom years of teaching has turned into a professional cynic. Later, Weston describes the students thus: “They’ll happily be part of the great London unwashed: illiterate, smelly, and quite content.” And he advises Thackery to “start brushing up on your voodoo if you wish to remain sane.”

It takes Thackeray only a few days to realize that Weston may have been right: his students are unruly and happy to be ignorant. The question To Sir and a whole genre of similar films asks is whether there is a way to reach such students; the answer they provide is not always the same.

In a film with a similar school setting, Blackboard Jungle (1955), Mr. Dadier (Glenn Ford) brings the students a collection of his old music records that he wants them to take an interest in, but which the young barbarians simply destroy. In another such film, Dangerous Minds (1995), the desperate female teacher (played by Michelle Pfeiffer) uses martial arts to get the students’ attention but is reprimanded by the headmaster for using “force” in a classroom, so she must find another method. She connects them to poetry as a means of fighting the danger in their own minds. Reaching students with poetry is also used in the 1983 film Educating Rita (starring Michael Caine) and in Dead Poets Society (1989, starring Robin Williams), just as music is used in Mr. Holland’s Opus (1995, starring Richard Dreyfuss).

But neither poetry nor music is part of Mr. Thackeray’s box of tricks, which is what makes To Sir, with Love so different from other movies about the challenges of educating the unwilling. His trick lies in the realization that the unruly students must learn to act like adults who, in a few months, will confront the “real world.” Forget math, forget literature, geography, and other subjects. Teach them to be adult men and women first: how to dress properly, how to behave towards others with respect, how to prepare a simple meal on a tight budget, and above all, how to deal with unfairness of the world.

“Will you use a weapon every time someone angers you?” Thackeray exclaims to the class, who feel outraged that another teacher had bullied one of the boys into hurting himself in the gym while attempting a vault. Life is not, in fact, fair, and that is one of the lessons Thackeray tries to teach his students, especially the boys, who will need to control their violent urges when things don’t go their way.

As for the girls, the lesson is to stop acting like tarts and using vulgar language. Thackeray wants them to learn to demand that men approach them with respect. He introduces a new rule: young women are to be called Miss.

As expected, Mr. Thackeray wins his battle, becomes the favorite teacher—the one known as “Sir”—and the young East End barbarians are transformed into civilized human beings.

In To Sir, with Love, Poitier is not just a black man; he is a black actor who comes to London from a former British colony. Originally from the Bahamas, a Crown colony where his father was a taxi driver, Poitier was a perfect fit for the character of Mark Thackeray, who comes to England from British Guiana, situated on the northern coast of South America. The colony became British in 1796, when it was taken from the French.

The country gained independence from Great Britain in 1966, becoming Guyana, and To Sir, with Love was released the following year. This timing can add to our understanding of the movie: To Sir, with Love is largely devoid of racial overtones; only a few scenes gently touch upon it. One of the boys in front of the school throws a metal can, which Sir catches, cutting himself in the process. A student’s spontaneous reaction—“Red blood!”—meets with an equally spontaneous answer on the part of another: “What do you expect, pinhead? Ink?” Weston’s “black sheep” and “voodoo” remarks, mentioned earlier, exhaust the list of references to race or racial differences. Even the students’ allusion to black women in Africa walking around almost naked is calmly answered by reference to differences in climate, which often dictate the way we dress. And the white students’ own untidy way of dressing, greasy unwashed hair, and foul language—even among girls—throw us back to Weston’s remark about “the great London unwashed.”

Apart from that, race is not an issue and seems present in the film only as a way to keep the viewer alert to the real issue behind it. That real issue is civilization: it is not about being black or white, but being civilized or not, being vulgarians or being ladies and gentlemen.

This is the prism through which we should view the movie; one of its lessons is that civilization is a way of acting and thinking about oneself and others. It is not about genetic makeup but cultural norms; when you break them, or never learned them, you are a barbarian and vulgarian. The black Thackeray may not be white, but for all intents and purposes, he is English. One cannot exclude the possibility that some of the students’ East End ancestors helped colonize Guiana. In so doing, they brought to Guiana the English culture that formed Thackeray. Colonization, despite what we are taught today, can have salutary effects, as it has in India, Nigeria, and Kenya, where functional educational and legal systems are the great British legacy that makes those countries successful.

Thackeray, as if irony were one of the engines of history, brings civilization back to London’s East End; and what the English Weston failed to achieve, Guianese Thackeray does. He offers his English students a civilized way of adult existence.

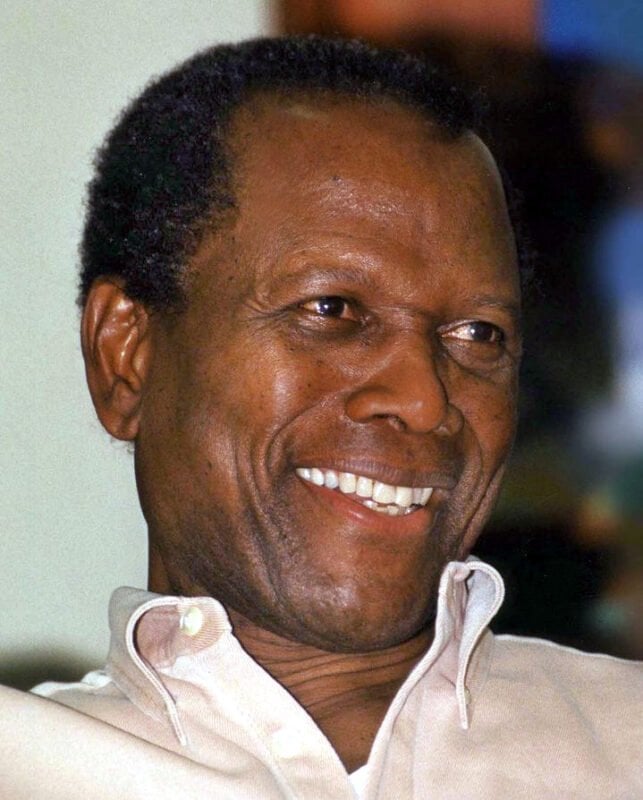

Unlike those who followed him, Poitier made a mature examination of blackness in American life a recurring theme of his cinematic oeuvre.

The movie may be optimistic in its message, but it is more realistic in its approach to education than any other movie of its kind. Inspiring teachers who reach students’ souls through poetry or music are part of the educational equation, but before they can be used, children must first learn discipline. As John Stuart Mill—an expert in thinking about civilization and barbarism—never tired of repeating, “a people in a state of savage independence … is practically incapable of making any progress in civilization until it has learnt to obey.”

Mill’s insight applies in the same degree to education as it does to civilization. It is a lesson that our Western educators and parents should learn as well. When they do, we will stop talking about race and focus more on the civilizing effects of discipline and culture on human nature.

Poitier was an outstanding actor. He won several prestigious awards, including the Oscar for Best Actor in 1963 for his role in Lilies of the Field. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 1974 in recognition of his lifetime of achievements. There is one thing, however, that distinguishes him from others, including other black actors such as Samuel Jackson or Denzel Washington. Blackness as such has been a theme for these actors, but generally in an exploitative or politically manipulative way. For Washington, this has been through his collaborations with the radical black leftist director Spike Lee, and for Jackson it’s through the genre films of Quentin Tarantino, which consciously mimic the blaxploitation movies of the 1970s. Unlike those who followed him, Poitier made a mature examination of blackness in American life a recurring theme of his cinematic oeuvre.

His 1967 film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (with Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy) confronts the problem of interracial marriage. It is sweet, somewhat naïve, and idealism is stretched to its limits. And even though the movie is supposed to convince the viewer that interracial marriage should not be a problem, the viewer who wants to stay married to a member of his own ethnicity does not feel he will be decried as racist for maintaining that preference. Typical racial prejudices, however, are considerably challenged in the film. Dr. Prentice, the black man who wants to marry a white girl, is not an ordinary man. He is a medical doctor, member of many international medical associations, with an endless list of publications.

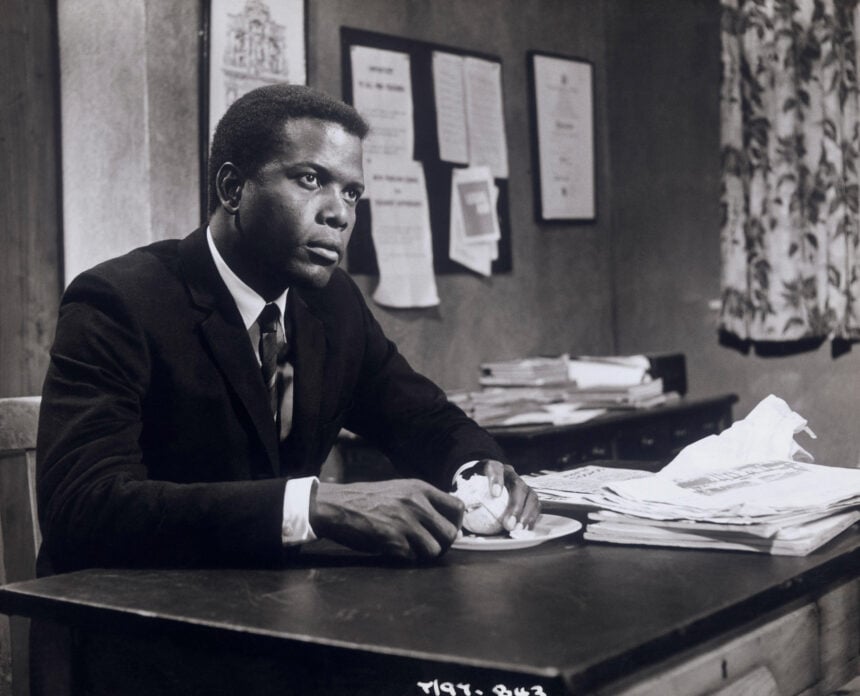

A similar argument is explored in In the Heat of the Night (1967) and its sequel, They Call Me Mister Tibbs! (1970). In both, Poitier confronts the problem of repulsive racism in a small southern Mississippi town. He is an elegant, educated policeman from Philadelphia who confronts white trash—stupid, vulgar, corrupt police who need him to solve a murder case they cannot solve. He is not just intellectually and professionally superior; in contrast to them, he is a deeply moral being. By displaying education and moral superiority to those who look down on him, he forces them to come to the realization that their racism is, in fact, a moral weakness.

(World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo)

A Patch of Blue (1965) explores the superficial nature of prejudice when a blind white girl becomes friends with a black man and develops a potential romance with him during the racial tensions of the

civil rights era.

The 1961 A Raisin in the Sun tells a story of a black family in white society. The family’s struggle to overcome obstacles gains the viewer’s unconditional sympathy. But the problem the family faces cannot be reduced to racism only. It is also an issue of culture, and in this case, of African culture. In the confrontation between Beneatha (sister to Poitier’s character, Walter) and her suitor, George, over what is “African culture,” we hear George blurt out:

Oh, dear, dear, dear! Here we go! A lecture on the African past! On our Great West African Heritage! In one second, we will hear all about the great Ashanti empires; the great Songhay civilizations; and the great sculpture of Benin—and then some poetry in the Bantu—and the whole monologue will end with the word heritage! Let’s face it, baby, your heritage is nothing but a bunch of raggedy-assed spirituals and some grass huts!

Needless to add, if Hollywood was to remake A Raisin in the Sun, this conversation would most likely be cut out entirely and replaced with some talking points from critical race theory.

One thing that Poitier’s career can teach is the art of being black without “acting black,” in the current sense of that phrase, which is often nothing more than the glorification of thuggishness promoted by the young generation of black actors. The most recent Best Actor Oscar-winner Will Smith’s publicly slapping the face of the ceremony’s presenter, Chris Rock, before millions of people all over the world is a good illustration of this degenerate behavior.

(John Mathew Smith / Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Poitier—who passed away in January—made his career in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, when racism was spotlighted at least as much as it is today—understood that acting in a civilized way is not a class or race privilege or part of a genetic makeup. It is a human obligation—something that makes societies genteel. He practiced a great art that should not be forgotten if America is ever to resolve its recurring racial crises.

Top image: Sidney Poitier as Mark Thackeray in To Sir, with Love (United Archives GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo)

Leave a Reply