My father has to go out in a storm. An eight-hour shift at the gasworks, then two or three hours tomorrow morning, All Soul’s Day morning, in a bar where “Happy Hour” starts at 7:30 A.M. and ends at noon, and he’ll walk home through the snow stinking of beer and CH4, the chemical composition of natural gas. If you want to know how it smells in our house, scratch and sniff the card the utility company gives you so you can detect a leak in one of your gas-burning appliances. What the company adds is an “odorant.” My father and our house smell like an odorant.

Pani or “Madam” Pilsudski, our neighbor, likes the smell when she comes over. “Oo-la-la,” she says when she gets a whiff. As my father grumbles and I page through my scrapbook of interesting newspaper stories, Mother starts talking to her in Polish in the living room. I try not to listen, having important things to do on my hobby.

My scrapbook has a three-ring metal binding and gray canvas covers. In light blue ink, I’m putting on the front cover, “STRANGE, FUNNY NEWS GATHERED BY ANDREW BORUCZKI.” The cover is hard to write on, and I have to go over the letters, almost carving them in. Because of it, the front cover looks sloppy, which, when he sees it, serves as an irritant, not an odorant, to my father, who is trying to raise me right and who, sitting here in a sleeveless undershirt with a tuft of hair curling up from his chest, says to me, “What’re you doing?”

“Studying my clippings.”

“Why you won’t think of me for one minute? I gotta go in this weather to the plant. Put the scrapbook away and ask ‘what can I do for my father?’”

When I do ask, he answers, “I don’t know. Just don’t bury your head in a scrapbook all a-time.”

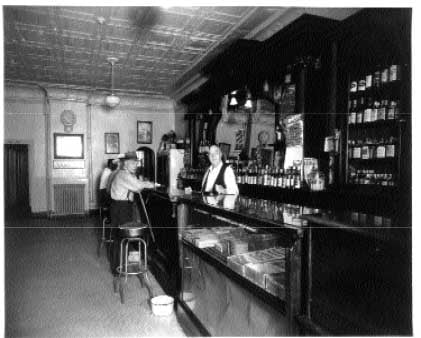

In five hours, he has to leave for work on a night the radio said would be clear and mild. The weather depresses him. His job, combined with his naturally gloomy personality, inspire him to get drunk at the Warsaw Tavern, especially now around All Soul’s Day. When the weather and your job stink, when your life is passing you by and you will soon be a dead soul yourself, why not go on a rumba? To relieve the pressures of my life, I can’t go to taverns like he does; but tonight, if he doesn’t stop complaining, I’ll do something else drastic and tomorrow’s newspaper will read, “Adolescent punches gas-stinking father during blizzard,” which will fit into my newspaper-clipping collection like this item from the Superior Evening Telegram. Right now the lead clipping in the news collection, it’s taped to a sheet of typing paper. In my scrapbook, the current No. 1 Best Story, Pick of the Week from the local paper of October 25-31, 1968, tells of a woman who ties her boy’s hands together, dresses him in a pig suit, then puts him on public display. It is from California, an Associated Press story. As further punishment, the mother hangs a sign on her boy in the pig suit. The sign reads:

I’m dumb pig [sic]. Ugly is what you will become if you lie and steal. Look at me squeal [sic]. My hands are tied because I cannot be trusted. This is a lesson to be learned. Look. Laugh. Thief. Stealing. Bad bo [sic].

“Mom denies abusing son dressed as pig,” says the headline. (I had to look up what “sic” meant.)

Another clipping reports on something closer to home. You will find it on page 2:

Child abuse

Gerard Minahan, Gordon, Wisc., used a marker to write “liar” in large letters on his ten-year-old son’s forehead, “I lied to friends and teacher” on his chest, and “I tell stories” on his back. Then he took his shirtless son to P&R Pub in Hawthorne and made him talk to customers and display the writings.

Now, my pop mutters, “They promised a sunny day, and look-it what we got!” He uses the Polish word for snow, “gnieg.” Four or five inches of it cover the birdbath.

“Maybe this’ll be my last Halloween,” I say. “Who’s going to give out candy on a stormy night? Darn this snow!”

“I geev candy,” Mrs. Pilsudski says.

“Boy’s too old for trick-or-treating,” my pop says. “What’re you, nineteen?”

“Fourteen. Tad’s nineteen,” I say, referring to my cousin. Home from Vietnam, he is named after Thaddeus Kosciuszko, the Polish patriot who helped General Washington win the Revolution.

“Ah, go upstairs,” says Pa. “Read your scrapbook. Play with your winter weed collection. Look at the weather. No, lemme tell you a thing or two. You know what’s falling outside?”

“What?” I ask as I leave the kitchen.

“Sh-t from the sky.”

“Sheet from sky,” Mrs. Pilsudski says, repeating in broken English Pa’s weather-related complaint.

“That’s northern Wisconsin for you,” Pa says. “Worst climate in the world is in ‘Siberior,’” which is a word he’s made up by combining “Superior and “Siberia.”

In the living room, I watch Ma and Mrs. Pilsudski, who whispers “sheet from sky” over and over as she stares out at the weather. Ma says we must be patient with Mrs. Pilsudski when she forgets and leaves open the bathroom door at our house, but I saw what she was doing once, and it was awful. She wore heavy black shoes, thick, skin-colored stockings, and a shapeless housedress with yellow cornstalks on it, a style of dress a lot of Old Country women around here wear. Girdle about her knees, the heavyset Mrs. Pilsudski, who cuts the calluses off of peoples’ feet for a living, hovered over our toilet. Through the open door, I spotted her busying herself, and I cannot say more on the subject. Tonight, with Mrs. Pilsudski worrying about getting home, she will wet our couch for sure; and, once Pani leaves, Ma will dab the cushion and say, “Be patient with her. Yes, she leaves open the bathroom door and dampens the couch, but patience please.”

“I’m going upstairs,” I say.

“You should give us all a break,” says Ma. “Go study your wildflowers.”

With the Lake Superior wind blowing hard outside, I sort through dried weeds, tape them to cardboard squares, write beneath each one “Wild Rye,” “Caraway,” “Tansy.” Tan and yellow weeds from our fields and woods keep me awfully busy. The weed-cards are fun. They pass the time for me like clipping newspaper items does. A brittle weed I collected once and mounted on cardboard, “Fireweed,” also has a news clipping beside it that kind of matches it. From page 10, Scrapbook:

Hot under the collar

Mourners smelled smoke at a funeral. When a mortician investigated, he found a fire inside a coffin. Investigators said embalming fluid leaking from the body of 42-year-old John “Jack” Peters may have caused a chemical reaction, touching off the fire.

Another clipping reminding me of no one or nothing—and certainly of no weed—starts, “Ashland, Wisc. woman charged with adultery” (page 11, Scrapbook). It tells that “enforcement of an adultery law attracted worldwide attention and is raising questions about the old statute’s constitutionality.” Then you read how over-the-road truck driver B.M. Bertilson asked the district attorney to prosecute his wife “under the law that hadn’t been used in Wisconsin in the 20th century.” Mr. Bertilson said his wife Lotty admitted breaking the law “while he was on the road” far from Ashland. What weed or plant could complement this story—Pokeweed? Bouncing Bet? Aaron’s Rod?

Another weed-mounted-on-cardboard, Heal All, matches a news clipping that recalls cousin Thaddeus. Page 13, Scrapbook, talks about a man dressed in robes and pulling a heavy wooden cross down the highway outside town. “Second Coming could be in the Northland” reads the headline.

The article said a man yelled “Praise the Lord” when a cop, who goes to our church, offered him assistance. Then, when the officer told him it was a highway hazard pulling this cross down the road, the newspaper article said the man offered “passive resistance,” so Lieutenant Gunski arrested him and the cross. On the way to town, Lieutenant Gunski stored the cross in the East End gas station back with the motor oils, then put the man in jail until his mother sent money to pay the fine. I made up a headline for this one: “Case of arrested cross.” But you don’t read the real surprise until the end. When the man with the “dark blond hair pulled back in a ponytail” got out of jail to get his property,

he placed the huge cross over his shoulder and trudged off. Only he’d rigged it so the walking was easier than it was on Jesus’ long haul up Calvary. “He had a neat wheel on the back of it. Still, if you’re dragging that sucker down the highway, it’s got to be heavy,” said the gas station owner, George Polkoski.

When snow is piled against the bedroom window and when the cedar tree is bent far over from wet snow, more news comes, a banging on the front door—Souls of the Faithful Departed walking in the storm. Soon, cold air shoots upstairs.

“Hey, look-it this!” I hear Pa say.

He likes Thaddeus, who’s just arrived but as suddenly disappeared. Thaddeus is one of many servicemen, especially Marines, to come from East End.

“Close the door you were breaking down out there a second ago,” says Ma. “You are sure in a hurry to get inside, Tad.”

As I head to the hallway at the bottom of the stairs, I watch Pani Pilsudski pulling an afghan over her shoulders. “Hey, where’d Tad go? He vanish from sight and become a dead soul?”

“I just told him to shut the porch door, that’s all,” Mother says.

“Good afternoon, everyone,” Tad says. “You’re darn right I wanted in. The thing I don’t like about the dark is it’s always dark. Geez, I took quite a fall outside.”

Though Thaddeus is too young to drink, people buy him beer and wine. He’s been on a rumba. A red-and-white wool tossle cap warms his ears. Over his haunted eyes rest blue, square-shaped sunglasses like The Byrds wear. He has on a knee-length, forest-green uniform overcoat with the red cloth patches on the sleeves showing he’s a Marine lance corporal. Snow sticks to one elbow and to the side of the coat. He’s fallen down and looks crazy.

“I’m out of uniform. You’re not suppose’ to wear sunglasses. It ain’t military,” he says. “What stinks in here? You let one, Mrs. Pilsudski?”

“Me! I stink,” says Pa. “It’s the odorant so you know what a real gas leak smells like in your home appliances.”

“We know what you smell like. Say,” Tad asks, “what kind of kid collects weeds for a hobby? And newspaper clippings? This ain’t normal.” He waits a minute. “No, I don’t think it is normal,” he answers himself, laughing.

My father stands in the archway between kitchen and living room. “How long you got left on your leave at home?” he asks.

“Tomorrow . . . tonight,” says Tad. “All Soul’s and Halloweenie.”

“Then where you go be stationed?” asks Pani Pilsudski.

“I’ve told you one hundred times, Mrs. Pilsudski,” Tad says. “Turn up your hearing aid.”

“No, you haven’t told us once,” Ma says.

“Wounds affected your memory?” Pa asks. “Have you seen his Purple Heart, Mrs. Pilsudski? Our nephew here is suffering wounds.”

She daydreams of something or someplace else and doesn’t answer.

My mother sure doesn’t think Tad’s showing up here drunk is very funny. During her happily married life near the Northern Pacific ore dock, she’s seen too many neighborhood men getting drunk, fighting, hollering, falling in the snow. It’s like in the Old Country. A weekly Polish paper, the Gwiazda Polarna, recently reported how a cold wave killed 36 people in Poland. Most of them were drinkers who went outside or fell asleep in unheated rooms. Just two old women froze, I read.

When Tad takes the heavy Marine overcoat off, we see how thin he’s become.

“I’m going back to Vietnam,” he says. “Can’t eat nothing. Can’t keep it down. Too worried.”

When he removes his tossle cap, a line divides the tanned part of his face from the pale part. It’s like this from his wearing a helmet three months ago. The pale part will never go away. I think he will be marked by this Vietnam war and by a pale forehead forever.

“Got you a present, Edda,” he says, pulling a bottle of vodka from the inside of the greatcoat. Next, he produces a paper he’s kept beneath his jacket.

“Going back to Vietnam. Goddam it, I’m going back.”

“Well,” Pa says, “you’re sure gonna have the last laugh on us, because next week you’ll be where it’s hot and tropical.”

“Over there, it’ll be the monsoon season, when your clothes get moldy green fuzz on them. Your shoes rot, too. It’s what I’m gonna call you, Andy—‘Mold Fuzz,’” Thaddeus says to me. “It’s your new name.”

“I like it,” I say.

“Your weather’ll be better than the siege of winter we’re gonna get,” says the gas man, my father. “It’s starting early this year.”

“I don’t want to go. I made a mistake, Uncle Edda. I’m okay. I signed up for a tour. Goddam. But I’m okay. I can’t remember if I said I was going back or not. I forget everything these days. Here—”

The vodka looks slightly greenish or yellowish in the bottle.

“Look, Andy!” says Pa.

In it is a stem of something. Thaddeus says, “European bison food. Distiller puts this herb in each bottle. It colors and flavors the product. ‘Cubrówka’ Bison Brand Vodka. I can’t recall where I got it,” he says. “Someplace where I was drinking last night. Read this to us, Andy Fuzz-Mold.”

The label says, “Flavored with an extract of the fragrant herb beloved by the European Bison,” I read. I turn the bottle sideways. The herb floating in vodka hypnotizes us.

“Gimme,” my pa says. “Let’s look at it.”

“You have to work, Edda. You can’t drink,” Ma says. Putting water glasses out for the vodka, she brings Mrs. Pilsudski her glass. “Jesu,” I hear Pani exclaiming after one sip. After two, I hear her singing a radio commercial for this wine that’s always advertised: “One sip of Arriba, and you, too, will hear the beat-beat-beat of the bongos.”

With everyone drinking, everyone crazy, I admit Tad looks great. He is cool. I don’t call him a “soldier”; I call him a “Marine.” A new kind of savage fighter in the Asian jungle, he dresses out of uniform and wears dark granny glasses, but despite what he looks and acts like when he is home recovering from his wounds, he wants to win the war. I’m glad he is a member of the Boruczki clan, and I hope I can put him in my Scrapbook of Brave Men under the heading “Cousin Thaddeus Milszew-

ski.”

Still uncertain of his feelings, I ask him, “Do you want to go to Vietnam?”

“Oh no . . . oh sure,” he says. “I’ve been wounded once. I’ll fight like heck.”

“Beat-beat go the bongos,” says Pani. “Oo-la-la. Smell goot in house.”

“It’s all right if you’re afraid to go back,” Pa says. “I’m afraid some nights at the gasworks.”

“I’m not afraid,” Tad says.

“That’s the spirit,” says my dad, clinking glasses with Thaddeus. From the kitchen table, my crazy-looking cousin picks up the piece of paper he brought in. Off-white in color, blank with no lines on it, the folded map is a foot long, maybe ten or eleven inches wide. When he opens it into two halves, we still see only the back part.

“Are you ready?” he asks. He drinks more vodka, nibbles a piece of herb. “You’ll see a map of your life.”

Pa sips his vodka. He gives me a drink of it in preparation for what Tad is going to show us.

Opening the paper to expose its four quarters, Thaddeus keeps the blank side toward us. We see eyes behind blue lenses, half-pale, half-tan face, two hands holding up the paper, which he then turns.

“Wow!” I say. It has so many lines, dots, squares. There are light blue and green places, pink and purple ones. You see thin lines and circles drawn in black. The map unfolded is at least two feet by two feet, I figure. When he spreads it out, the paper covers much of the kitchen table.

“What is it of?” I ask before I see that blue represents the lakes and rivers of our home . . . of the “NE/4 Superior 15’ Quadrangle of Superior, Wisc.”

“It’s as topographic as I’ll ever want to get,” Tad says. “I ordered it through the mail. I’m gonna educate the Viet Cong.”

Overcoat off, he hangs his green uniform jacket on the back of the kitchen chair, then smooths the jacket. His tie and shirt are tan. The lance corporal rank insignias on the shirt sleeves are darker green than the lime-green parts of the map. “The VC will see and fear Superior, Wisconsin,” my cousin says. “They will learn to fear Superior, especially East End. They will feel the wrath of a true son of the East End.”

“Take a drink,” says Pa to me. “Say ‘oo-la-la,’ Andy. Smell CH4.”

“I like the smell on your clothes, Pa,” I say.

Nibbling herb, Tad says, “I need strength to go back there. It’s gonna take real guts to show them my wrath.”

“You need a map of home,” I tell Tad.

Among various features on it are:

1.lime-green colored swamps and wetlands with blue marks like these to indicate marsh grass.

2. our town in pink with symbols on it for churches like St. Adalbert’s; symbols for schools, docks, railyards, sandpits, the hospital, the cemeteries; for roads that cross through woods, creeks, and swamps; for railroad trestles symbolized like this. One of the biggest trestles stands here by ours and Mrs. Pilsudski’s house.

3. the creeks and the blue rivers, one flowing to the southwest and off the map, another flowing north past our house to the bay, then out into the largest freshwater lake in the world.

Looking at the map, my cousin pours another drink. In the living room, Ma and Mrs. Pilsudski talk about the weather.

“The leg?” Pa asks Thaddeus.

“Healed up okay. In two weeks, I’ll be over there with this map. Sprout,” he says to me, “I’m going to promote you from a non-entity to a Private First Class. ‘To All Who Hear These Presents, Greetings,’” he says like he’s reading a proclamation. Then he gives me a blue booklet whose cover reads in black letters:

CONSTITUTION AND BY-LAWS OF THE THADDEUS KOSCIUSZKO CLUB

Composed of All the Slavic People in the Superior, Wisc. Area

Organized August 1st, 1928

“I joined up,” Tad says. “All you have to do is pay the membership fee, first year’s dues of six dollars, and prove you’re Polish, which ain’t hard in this neighborhood. I wanna lay claim to being in the Polish Club of Superior. If I get killed in Vietnam, then at least you’ll always know I joined the Club. I’ll have a map, too. It’ll be close by so a medic can get it for me while I am dying. In the newspapers, you’ll read about there being the casualty of a hometown boy. Sh-t, I’m gonna have to leave home!” He kisses the map. “Edda, the Purple Heart is authentic. They gave it to me. But what did I get it for? I hate to tell you this. I might never see you again. Geez, I’ve had too much beer tonight—I’m a cook, Edda. Christ, like Mrs. Pilsudski or some Polish baba. A cook! Never told no one. The guys like my cooking. They ask for pierogi when they come back from search-and-destroy operations near An Ho. Pierogi, of all things. Oh, I’m glad I joined the Club.”

It is like he is almost crying, but I know Tad is strong, and he is cool in sunglasses, and even Pa thinks so and will not accept that Tad is only a cook in the Marines.

I take a sip of Tad’s vodka.

“Andy, don’t let them have no more in there,” Ma calls to me. “And what are you doing with the men?”

“It’s a map,” I say. “He’s got the Polish Club membership rules with him, too.”

Trying to change the subject from Tad’s culinary art, my father points to the Left-Handed River my cousin’s just kissed. Pa is saying, “These lines show the height of hill and valley. You read the lay of the land by them. The purple waving lines, the contour lines, represent ten-foot intervals. Says so right here. You don’t needa believe me, but you should believe what a map says before you on this very table in a Polish household.”

Where both my grandfathers rest in the cemetery, the Nemadji River, also called Left-Handed River, sweeps in a wide blue arc on the topographical map. Flowing beneath the Chicago & North Western trestle, the river runs through a swamp, then past more neighbors’ houses.

As Thaddeus bends to kiss another area of the map, I figure that, according to the contour lines, the land above the river must drop 30 feet as it nears the bay. All of this is marked on the map. Sometimes, in real life, the Left-Handed River reverses course. Instead of entering the bay from the south the way it does, the river appears as if it’s running back to where it came from. This happens when northwest winds create whitecaps on the lake.

“If I kiss the place,” Tad’s saying, “then I’m okay. But how do you kiss a neighborhood? I’ve never done nothing brave. At least lemme study this map a little and get some strength.”

“You’ll be home soon. You’ll be discharged.”

Surprised by something on the map as they are talking, I point to it, telling them to look. Pa must swallow his Cubrówka the wrong way because he has to cough. “It’s the old railroad water tower near the bay,” he says. “‘WT’ means Water Tower. I forgot about it. Now my kid spots ’er. The round tank, the funnel that trains got water from. Great. You’re some map reader, Andy,” he congratulates me. “The water tower has been torn down for a long time.”

“What’s this on the map, the ‘Pesthouse’?” I ask.

“It’s not here anymore,” he tells me.

“Am I here?” asks Tad. “Do I exist? Man, too much beer and vodka.”

As we study the map’s contours as though they were contours of our lives, Pa says, “In purple at the bottom it’s got ‘Revisions compiled and map edited 1964.’ But over here . . . ‘Topography from aerial photographs taken 1959.’ It’s 1968. I’m looking at ’er and seeing that things have changed. No ‘Home for the Aged.’ No ‘Poor Farm.’ No ‘Pesthouse.’ Tore down so many years ago like other things. I suppose it’s how they do things at a map company.”

“I don’t know why they sent me an old map.”

Despite the dated topography, Tad kisses it again, and I wonder, could I ever feel such love for the East End?

It is strange when the church bell rings. At six o’clock, storm or not, it rings everyday; but now the kitchen clock reads 6:07, and we’re examining a map of old places, and the bell rings and startles me.

It must be the weather; snow changes contours. In winter blizzards, in summer heat, I’ve heard the bell as I explored beneath the trestle, floated in Burbul’s canoe on the river, or walked over the ice on the bay before the first snow. I’ve heard the bell out on Hog Island and heard it at the cemetery above the Left-Handed River. Always at six o’clock. Now today, it rings late.

In the living room, Pani says “beat-beat.” Her head falls. She dozes.

“Rivers don’t change,” Tad says. “Goddam. I’ve gotta do a brave thing. I want to be remembered as the East End man who wore a Purple Heart on his chest. Oh, this heart, Uncle Edda and Fuzz Mold! A crate of large eggs fell on me. Then a barrel of S.O.S. on top . . . chipped beef, chunks of ground beef in a cream sauce. ‘S.O.S.’ is short for ‘Sheet on a shingle,’ as Mrs. Pilsudski would say it. There mighta been bread involved in this incident, five or six loaves. Throw in sausage links. Throw in oatmeal. They all fell. A food accident crushed me. I have the leg to prove it. We were going to the field to bring a meal to the grunts. We’d rewarm it when we got there. Intelligence said everything was hunky-dory on the road. They cleared us to go. Our truck convoy carried field stoves, food, ice for tea, immersion heaters for the troops to dip mess kits in hot water after chow—

“Staff Sergeant Farrazzi was up in the cab with the driver. We didn’t rope stuff down good. Only the eggs were tied in a little. The driver swerved to miss a peasant walking his water buffalo . . . the peasant was heading through this storm swirl of butterflies, which the driver swerved to avoid. The driver’d got his military license for that weight of truck only a month before. Here I am a lance corporal who’d made many a tasty soufflé and who wanted his Belgian waffles to be the best in the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, and I’m wounded by eggs and bread. I’m drunk. Do you know Ho Chi Minh collected butterflies?”

“Don’t talk none about war,” my pop says. “You’re my sister’s boy. It is a shame you can’t feel like a hero. I don’t believe what you told us. You’re no cook. You’re a hero, though drunk.”

“I could make you something to eat,” Thaddeus says. “Eggs and toast, kielbasa and eggs to prove my courage. Everybody likes Polish sausage.”

“Won’t kielbasa remind you of combat?” I ask.

“What are you talking about?” Mother asks. “Get your cousin a cup of coffee right now, Andrew. He has to sober up. You all sound rattle-brained. Stop drinking before you get too crazy. Straighten up.”

“He don’t need coffee,” says my father, pouring him a glass of Cubrówka as Tad tries to speak Polish. Outside, tree branches and pine boughs litter the snow. Drunken night, Polish words, storm, map. We sit in a kitchen where I think the contour of a life, the history of a life, must run like purple lines that show its depth, and I suddenly believe this map of Tad’s should include other people who’ve lived in the East End of Superior and sat together on stormy nights in kitchens, as well as the people on the Old Country map you see at the Warsaw Tavern. Such people are never far from us. Now Tad is making a place for himself on the map of memory. I am trying to, too, by thinking that in the forest among the storm’s windfall of trees and branches this very All Soul’s Eve, departed souls are waiting for another soul to depart—this one for Vietnam. Maybe it is storming in Old Country Poland, too. It is possible, I think, that the herb connects us—the herb, our history, and this old Polish language Thaddeus is trying to speak.

Now Ma tells Pani Pilsudski, “Don’t worry. We’ll get you home.”

Helping her up, Mother hugs her so she knows she’s okay. As Mrs. Pilsudski puts on her wool coat and boots, I throw on a jacket, push open the porch door against the storm.

Between our house and hers, two feet of snow drift over the sidewalk. On the nearby railroad trestle, a train passes quietly. When we’ve crossed the new contours, Mrs. Pilsudski thanks us, tells us she will say a rosary for us. “Arriba,” she says. “Beat beat bongos.”

“Arriba,” we say. “Beat beat.”

I figure Thaddeus will now return to his map; but he goes off—tossle cap, blue sunglasses, and uniform overcoat on—stumbling into the wind, maybe wanting to find a home, maybe wanting to find the Polish Club. “I’m doing fine,” he’s saying.

I lose sight of him in the storm and can’t watch anymore. As I walk back in the house, I see Pa stumbling a little but know he’ll be okay.

I page through the blue booklet Tad gave me. Sixteen pages in Polish, a language I am trying to study but now need Pa’s help to read. “Celem Towarzystwa Bratniej Pomocy in. Tadeusza Kogciuszki. . . ,” it starts, then goes, “bidzie skupienie pod swój sztander Polaków, ku wzajemnemu i moralnemu poparciu. . . . Look-it. ‘The Club’s purpose is the gathering of Poles under their own standard for mutual and moral support,’” I say, reading in Polish after Pa how the Kosciuszko Club and Lodge is also for

the fostering among club members of the feeling of love and brotherhood, for the defending of Polish honor, and finally for the furtherance of the principles and immortal deeds of one of Poland’s greatest sons.

“It’s a symbol,” Pa says.

“You’re drunk, Edda,” Mother says.

“Drinking’ll kill me,” says my father.

“Go to bed, Andrew,” Ma says as the telephone rings.

I answer it. Mr. and Mrs. Novazinski are both talking at once: “Andy! Your cousin says he wants to kiss our walls and floors while he’s out trick-or-treating. He never wants to leave East End, he says. We gave him some candy, told him to get going. Call his house. Tell his parents the kid’s crazy drunk.”

Handing Ma the phone, I go upstairs. I stare at weeds. I read a little in a book. When people die in houses in the Old Country, it says, mirrors are turned in to face the wall, and windows are opened so the spirit isn’t trapped inside the house.

Thinking no one has died tonight, I still turn my one mirror backward to the wall when the phone rings again.

It rings again later. It must be for Tad. Then my dad is in the next room getting ready for work.

“Hawkweed, Tansy, Goldenrod,” I whisper to the weeds of my collection. Mirror turned, I quietly raise the window, then the storm window behind it to let out the spirits of the dead—or in Tad’s case, the living. The warm air of spirits rushes out through the screen. I have followed the old custom.

Hearing Pa go downstairs, I stop whispering and think there is finally peace this night of souls, until a little while later I hear a pounding on the storm door. As I peer through the window into the swirling wind and snow, I see Thaddeus in uniform.

“It’s me,” he’s saying, drunk, frightened. “It’s Thaddeus. Remember where I stood on All Soul’s Eve. Don’t forget where I stood.”

“You’re no Kosciuszko, Tad,” I say to him from my window.

“I know. I want to be. I want to win the war. I want to be a hero.” He’s holding open a paper bag. “See? This is a start. I got a bag full of candy. I can do great things if I set my mind to it.”

Downstairs, the phone rings again. I hear Ma’s voice through the furnace register. “Tad, it’s people,” I yell out to him. “They say you’re kissing their houses, you’re kissing their porches and steps . . . even their doors and mailboxes. Your folks are pretty angry. My pop sure is, with the phone ringing so much. Be careful out there, will ya, Tad? Don’t drink no more. Don’t go trick-or-treating no more.”

“I won’t,” he says.

He kneels down to clear the snow with his hands. I see the earth he has discovered that he loves. I see this one dark spot in the world of white. He is kissing the center of the world.

When Pa steps outside on his way to the gas plant, crazy Tad, like he can’t take his hands from the cold earth of northern Wisconsin, is working at the snow, saying, “I knelt here once. Remember me. Remember where I stood and knelt. Remember the earth I kissed just as winter came.”

When Pa looks down, Tad says, “I’ll show the Viet Cong something they’ll never forget. Oo-la-la, war is hard.”

Still stumbling from the Cubrówka, now Pa kicks at the snow to clear a little more away, as if this could keep Thaddeus in the East End forever.

Leave a Reply