Named Stefanie Karawinski, I’m seventeen years old. The woman in the title of the story, Sister Mary Leokadia, is perhaps fifty. Because the nuns at my grade school here in Superior wear black habits and white, scarf-like wimples covering their hair and ears, I can’t tell their ages. They belong to an order founded for Polish and Polish-American women: the Sisters of St. Joseph of the Third Order of St. Francis, whose main convent is in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, where I’d stop on the way to Milwaukee if it weren’t so far out of the way.

Though this story is about my family, and principally about my dad, and has only a little to do with Sister Leokadia, I’m still naming it for her. Because the nuns do so much for us, and yet remain in the background of our lives, credit is due them. I’m entering Marquette University in the fall partly because of the nuns. Though after attending Szkola Wojciecha, St. Adalbert’s grade school, I went to a public high school, I’d still see the nuns in church; they’d have me do odd jobs for them at school, and sometimes Sister Leokadia would visit our house. Because she’s a holy presence in the neighborhood, this story is named for her, the nun who taught me in seventh and eighth grades.

I’d never name a story for myself. I shouldn’t even use “I” so much, but how else to describe yourself when you’re a character in your story? I have medium-length light-brown hair with bangs. In back, my hair is straight, trimmed evenly across. I wish I were as pretty as Mother. I try to be modest in speech and dress, to read a lot, to study writing in the months before college. A tall girl, I blush when teased. I have pale skin. Who isn’t pale in June with winter not long over in Northern Wisconsin? I wear glasses for all the reading I do. A photo of Stefanie Karawinski, author and minor character in this, her family’s story, would show an average girl, plain in appearance, which is true.

I live with my parents and Dziadua, Grandpa, a retired seaman in poor health, in a house in the East End. So you’ll know both the heredity and environment that shape my life, I’ll describe the two lower floors of our house, starting with the basement, where dustwebs catch on thin plastic window curtains. In the basement fourteen years ago, Dad built plywood cabinets. During winter, the basement—which, in other seasons, is damp and cool—is the warmest place in the house, for in the center stands a furnace converted to burn natural gas. Tin vents rise through the house carrying warm air to us up here, too. Along with the basement workbench and the furnace are the washing machine, laundry tub, scrub board, and the old coal bin, now made into a storage room. Sometimes even on Memorial Day, the furnace comes on.

Most of our time is spent upstairs, where the cabinets Dad built hang above the sink on one wall and above the refrigerator on another. Other cabinets stand next to the stove. We probably have more plywood cabinets in our kitchen than any household in East End. The door frames and the doors to the back porch and the dining room, wainscoting, baseboards, and other wooden kitchen surfaces are painted with ivory-colored enamel. The kitchen wallpaper is yellow. But what you recall about the kitchen is the plywood cabinets with the clear, reddish-brown stain on them to bring out their grain. I hardly remember the days Dad built them, but I know it took strength for him to work eight-hour shifts at the shipyard, then come home to care for the house—painting it, changing storm windows, cutting the grass outside—then to go down the basement to his cabinet project. I think he is the strongest man alive.

Here are four reasons for my thinking this: His gruff boss, who doesn’t shave and can’t pronounce Polish names, thinks Dad, because of our last name, likes to be called “Car Wash.” When the boss yells, “Car Wash, do this,” “Car Wash, do that,” Dad smiles. Everyone believes Dad’s good-natured; but I think his smile means he’s stronger than most for not losing his temper, which he has a right to lose, considering he had a life-threatening accident in the same shipyard where the boss makes fun of him. Self-possession is one of Dad’s great strengths, and there are others. Example two, for instance: He labors all year in cold and snow, heat and pouring rain. Or example three: In addition to being called Car Wash and working in bad weather, he suffers another insult in silence: Across the highway from the Great Lakes freighter the men are lengthening in dry dock stands a Greyhound bus. Nothing else is there but the Greyhound, which a 1940’s baseball team or band toured in—no buildings, no trees, just the broken-down bus with flat tires that someone parked in the field. On a piece of cardboard over the smashed front window, the owner has written, “POLISH SKI TEAM.”

Stanley “Car Wash” Karawinski says nothing about this. Nor, for my fourth example of his strength, did he say a word when I went with him on his bicycle to The Alibi Tavern and a drunk yelled, “Hey, Car Wash, you’re Polack, right?” When Dad didn’t respond, the guy said, “Well, a Polack’s nothin’ more than a sand-blasted nigger.” Though I was only thirteen at the time, I thought about telling the drunken man to be careful who he was talking to, but Dad laughed and left with a bottle of brandy for Grandfather.

He looked shaken on the way home, his face set in the grim smile he’s had since the accident. “He shouldn’t call black people that or call us Polacks,” he said.

When we parked his bike in the garage, he was bothered he hadn’t answered the guy in The Alibi. Yet I know a strong man can have a peaceful heart. Violence would have done no good. Though he didn’t stand up for himself, I knew my father had honor and integrity. No matter if people called us Polacks, he always cared enough about the country of our ancestors to fly the Polish flag in our yard. Today, we also have a decal on our front window—over a red eagle, the word SOLIDARNOSC, SOLIDARITY, in white letters; for in Poland this year, the Communist government raises food prices and dismisses workers from shipyards and coal mines and keeps Solidarity leaders in concentration camps. Dad cares about this because he is also Polish and works in a shipyard, where he pedals to work on Mother’s old bicycle, a Schwinn with thick tires, a blue frame and fenders, and a white seat. In bad weather, Tony Stromko gives him a ride.

But I should describe the rest of our house. On the table in our dining room stands a statue of the Virgin Mary; under Her is a lace tablecloth. Thinking that the Blessed Virgin had Her favorite television programs, when I was young I used to turn Her statue toward the TV room next to the dining room. Now Grandfather, who has emphysema and needs his privacy, lives in that room. For the Mother of God, there’s not much to watch on TV, anyway. Behind the crucifix on the dining-room wall, my mother tucks the palm frond after Palm Sunday Mass; and in the TV room are Dziadua’s bed, an end table with a lamp on it, and a commode, because it’s hard for him to get to the bathroom during the night.

We call the last downstairs room the “front room.” If you look in from the yard through the picture window, you’ll see a piano, phonograph, sofa, desk (on it a framed picture of Dad as a young man when he was still O.K. before the accident), comfortable chairs, and a large wall mirror. If you look out the window, you’ll see Washington Park stretch from 4th to 5th Street and from 25th Avenue East to the railroad tracks that run to the Fredericka Flour Mill. This is the downstairs of a house of memory.

Because Dad can’t talk much on the job, he keeps everything stored up till suppertime, when out come the most beautiful stories as well as fantastic tales that a soon-to-be Marquette freshman shouldn’t believe, like the one about Mr. Novotny, who wore a hook on his arm after an industrial accident. How can you anticipate a story like this?—that Mr. Novotny welded his hook to the bumper of a car. Yet Dad insists it happened. He says: “I heard him calling, ‘Help! Someone help!’ The poor, drunken Novotny is crying when he sees me. His shirt’s greasy, his pants sliding down his hips. ‘Get me loose, Car Wash,’ he says. Giving a pull where Captain Hook welded himself to the bumper, I broke him free.” (The indentation in Dad’s forehead from the accident grows shallower as he tells us the story.) “So he stands up, thanks me, stumbles out the garage door, reaches up with his hook to clamp himself to the clothes line he rigged from there to the house, and guides himself by the rope across the yard to the back porch.”

“It’s a safety line for drunks,” Grandfather says.

By now, Dziadua and I don’t know what is true or false. Then Dad tells the story of how, when he was sailing on the Great Lakes ore carrier Arthur M. Anderson, the ship was inundated by migrating warblers that settled on the deck at dusk, awoke at dawn, then flew on their journey north. “Thing is,” Dad says, “they lost ground because we were going southwest.”

This is the mysterious “Car Wash,” the storyteller—Stanley Karawinski, who stands six-feet-one-inches tall, shoulders slumped when he walks, who has a twist of brown hair partly covering his forehead and a ruddy face from working outside. He hears rumors and gossip and wants exciting things to happen to him, though how could he have been at Novotny’s and at work at the same time? I give him the benefit of the doubt concerning the truth of his stories. On the other hand, why was he quiet in The Alibi Tavern or after Sunday Mass when people stood out front of church? Mother does all the socializing there. I think Dad is “slow” from what happened to him when a gantry crane dropped a hull plate to the earth; hitting the ground, it banged against a smaller crane and struck him. Then, I reassure myself that because he rides a bike with a wicker basket tied to the handlebars, doesn’t hurry his speech, and usually only talks at home doesn’t mean anything bad. Figuring he’s still capable of accomplishing big things in life, I apply a saying to him Dziadua taught me: “Krowa co duzo ryczy, malo mleka daje” (“Great talkers are little doers”). Outside of our home, Dad is no talker.

Last week, while we were waiting for him to come home from work, Mother was preparing supper, Dziadua was at the table, and I was in the pantry off of the kitchen thinking back on high school, specifically how one teacher says reading Polish names is like reading an eye chart. After you heard it a thousand times—Polish names equals eye chart—it wasn’t funny. Right off in our freshman year, he shortened Zawistowski to “Zowie,” Kiszewski to “Kazoo,” Waletzko to “Waldo,” which is like what happens to Dad’s name at the shipyard. This is the same teacher who, if you wrote a confusing sentence on the board, called it a “Polish sentence” in front of everyone, no matter if you were Polish or not.

Trying to forget all that, I went to the kitchen table, where Dziadua read the Marine Vessel Traffic part of the newspaper to see which Polish ships were upbound from Sault Ste. Marie to the Port of Superior. Boats with names like Ziemia Chelminska, Pomorze Zachodnie, Zakopane, and Ziemia Bialostocka have put in here a hundred times to load grain and flaxseed. Dziadua was like the harbormaster of our house, the way he knew everything about the port. I couldn’t get mad at him; for when he looked at me, it was like he was asking, “Why am I a widower? Why are my lungs failing? Why are my days at sea over? Why did my son get hurt in the shipyard?” When Dziadua tapped his fingers on the tabletop, I got his watch or fetched his sweater from the armchair. “Can I do anything else for you, Grandfather?”

“It’s hard to breathe in here. There’s nothing anybody can do,” he replied.

“I know. Is there a Polish boat in this week?”

“Ziemia Gnieznienska at Harvest States Elevator,” he might say. “Let’s talk when there’s more air.”

“I’d like to talk about the boats with you,” I told him.

Then I started thinking why about my own life. I was sick of hearing our names look like eye charts, of hearing about “Polish sentences.” I even heard a radio disk jockey announcing the winners of free concert tickets say, on the air, “another frickin’ Polack name” when he stumbled over a good name ending in czyk. Why do people say such things when my father spent a year on a gunboat on a river in South Vietnam; when Dziaduasailed waters patrolled by German U-boats during World War II; when ten Polish seamen have jumped ship in Superior to start a new life here; when, on this very day, coal miners and shipyard and transit workers are fighting the communists in Poland? How can someone joke about such strong men? Of all ethnic groups, the Polish seemed to be the ones people got away with ridiculing.

Having put supper in the oven, Mother was in the front room listening to the phonograph, a polonaise by Chopin. She said it expressed Polish peoples’ courage and spirit. The polonaise reminded me of her. So did a prelude called “The Revolutionary,” which Chopin wrote in Paris to honor the 1831 Polish Uprising against the Russians. A dreamlike nocturne reminded me of my father. I was too young to know much of what he was like before the accident, but I knew I admired him for what he’d been through.

Nocturne

Prelude

Polonaise

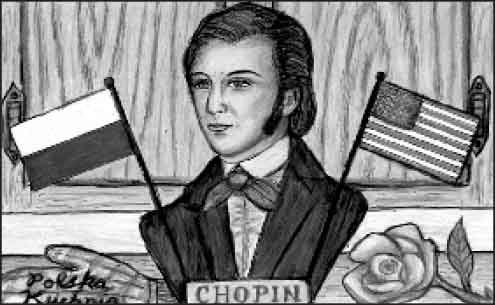

Once, on the gym stage, before a program the nuns sponsored, Sister Leokadia placed a bust of Chopin on a pedestal. I’d come to turn the pages while she played. After she finished practicing the piano, she told me to wait for her while she went to get something. When she returned, she gave me a yellow rose to place on the pedestal. The American and Polish flags stood on either side of the bust. “Go ahead, Stefa,” she said. After I put the rose before the great composer (as I will present my father a rose some day when I show him my Marquette diploma), I touched the stars on the blue field of the American flag and held the red-and-white Polish flag. Kissing both flags, I heard Chopin’s music in the still air. He is dear to the hearts of Polish people. In the national anthem of Poland, which begins “Jeszcze Polska nie zginela” (“Oh, our Poland shall not perish, while we live to love her”), you hear the strains of a polonaise. Polish money has Chopin’s picture on it. A famous statue of him stands in Lazienki Park in Warsaw.

With summer passing, I was thinking, as Mother played Chopin on the phonograph, how I’d miss the house, the nuns, and my family when I went to college. Then the door opened, and the bicycle rider stepped in.

A stranger stood on the back porch. Looking like he was thirty-five or forty, he wore a sailor’s blue watch cap, his hair sticking out from under it. A brown suit coat hung off his shoulders, the cuffs pinned under to shorten them. A cream-colored shirt stood out from beneath the coat. As I was thinking how out of place the man looked, Dad said, “Gosc w dom, Bog w dom” (“A guest in the house is like God in the house”).

“Who’s this?” asked Mother. She was always patient with Dad. Smelling cigarette smoke on his clothes, she knew he’d been drinking somewhere.

“He’s off a ship. We were in The Warsaw Tavern. There’s an article in the paper. ‘Immigration mum on ship-jumper.’”

“That’s the Polish boat Ziemia Gnieznienska that was in port,” Dziadua said.

When Dad grows excited, Mother has to calm him. “We have a Polish sailor right here,” he was saying proudly.

“Pleace, I am . . . ” said the man. Leaning against the sink, he looked sorrowful, beaten-down.

“No more beer, Stanley,” Mother said to my dad, trying to coax him into his usual routine of telling stories.

“Here’s a story for tonight,” Dad said. “Tell us what happened to you, Wiktor Urbaniak.”

Unsure of his place in our midst, one minute the sailor tried to stand up straight and smile at us. The next, his forehead would wrinkle, he’d look angry, his shoulders would slump. “Buk-ser,” he said. “I am in America six days. If I stay until ship leaves, then Immigration Office not so much problem for me. There would be no way to go for me to Poland. When I left ship, I shouted ‘Kommuneest!’ at the captain, crazy man yelling down from bow. Instead of taking the taxicab, I am ending up with longshoreman who I am lucky was in his car watching. Now I am reported to Immigration and Naturalization. Buk-ser, Buk-ser,” he repeated.

Dad got a bottle of beer for himself and for our visitor. “Ten sailors have jumped ship here in five years,” Dad said. “All in Superior, and I’ve never seen one till now.”

“No beer for either of you,” Mother said. “And that sailor is already drunk.”

“But I have to join him in Solidarity, Helen.”

When Dad finished sipping his beer, he went in the dining room, returning with his camera and with articles he’d been saving about shipyard workers in Gdansk. “I’m also a shipyard laborer,” he told the sailor. “I’ve been keeping up with your history like we’re one and the same. I’ve got a Solidarity sticker in the window.”

The sailor signaled me to get him another beer. I was afraid not to. He had scars where his eyebrows joined the temples. He had a mark on his forehead. It was like his face had been smashed up.

Dad pointed to his own forehead where you could see the effects of the accident. “See where I got hurt? Did the Secret Service do that to your face? Helen, take a picture of us.”

“Buk–ser,” said the seaman.

“I had an accident,” Dad said. “Hull plate missed killing me. I got banged up.”

“If you want to stay in the U.S., you better not drink so much,” Mother said to Wiktor Urbaniak. “You’ll need to go to INS again.”

“Helen, Stefa,” Dad said, “you don’t know what’s happening in your own kitchen. This is history taking place with him here. They arrest people in Poland all the time. I have an interest in things as a shipyard laborer. I know they can’t beat down our spirit.”

“You don’t know Solidarity from the dairy store,” Mother said.

“Buk–ser,” said the sailor.

“By golly—here, stand by the stove so people will know it’s in our kitchen we took the picture,” Dad said. “Make a V for Victory and smile. Here, hold this, too.” It was an oven mitt that said “Polska Kuchnia,” which means “Polish kitchen.”

Ringed by the stove, refrigerator, plywood cabinets, the sailor tucked his square jaw into his chest. He swung a fist as though trying to loosen up his arms and shoulders.

As Mother said, “I know what he’s saying. He means he’s been a ‘boxer.’” Dad said “Solidarity” and whistled the “Hymn to Solidarity” that the Gdansk workers rally around.

When Dad extended his hand to him, Wiktor Urbaniak’s hand came back in a way Dad didn’t expect. The sailor had had enough picture-taking. Not yet realizing what the drunk sailor meant by the word, when my father said “buk–ser,” Wiktor Urbaniak put up his guard.

Dad blocked the punch the sailor threw. It was as though Mr. Urbaniak off the Ziemia Gnieznienska was shadowboxing.

“What’s he punching anything for?” asked Mother.

“To show his solidarity with me,” Dad said.

Moving his head from side to side, the sailor looked between his fists, oven mitt on one hand. “Problem?” he said, pronouncing it “Pdob–lem,” as he threw another punch that missed.

When my father dropped his guard, saying, “Hold on a second; I said ‘Solidarity,’” a fist connected. Dad’s eye swelled. He got hit again. I heard the wind rush out of him as he muttered “Poland.” Trying to clear out what he’d just learned, my dad shook his head. Tasting his bloody lip with his tongue, he was saying, “There’s been a mistake.”

When Dad’s smile returned, Mother, angry, said to the sailor, “He’s not right. Can’t you see? Why do you think his forehead’s like that and he rides a bicycle everywhere? He’s not been O.K. for fourteen years. His daughter is the only one who can’t see that,” she said, pointing to me. Then, to the sailor, she said, “You’re getting out. Come on. We don’t want you here, Solidarity or not.”

I didn’t know where they took the sailor. As my dad washed his face, trying to sober up, Mother and Dziadua drove Wiktor Urbaniak back to The Warsaw Tavern or to the immigration office. I didn’t care where, not while Dad sat at the kitchen table talking to himself, head in his hands. He couldn’t figure what’d happened, but I knew that a drunken immigrant seeking asylum didn’t care what “Car Wash” Karawinski thought about world affairs. They lived in different countries.

Seeing Dad bewildered, I wanted to do what Sister encouraged us to do in our lives. She’d say it over and over, “Nigdy nie przegap okazji, zeby powiedziec komua ze go kochasz” (“Never waste an opportunity to tell someone you love them”). But I couldn’t do that right now, not when he was so busy shaking his head as he tried to explain things to himself. He was talking in a whisper about Gdansk, about The Alibi Tavern, the shipyard . . . everything that made him feel special.

When he said he was all right and wanted to be alone for awhile, I went out to the garage for his bike. With Grandfather and Mother still away and my dad resting, there was no one to talk to. The house and yard were quiet. A far-off train whistle made me lonely. What did all this mean? I wondered as I rode the bike across the lawn to the front sidewalk. By the time I turned toward St. Adalbert’s School, it was dark. You could smell lilacs, and I was glad to be out of the house. There’d been drinking and rough talking in our Polish kitchen. Dad had been embarrassed he couldn’t stick up for himself. I figured what happened would cure him of the need to talk after work. Earlier, during the drunken chatter, he told us that Alphonse Zukowski, a Polish man who ran the auto-body repair shop on Winter Street, owned the Polish Ski Team bus. I guess Mr. Zukowski thought it was harmless for Polish people to laugh at themselves or to be laughed at by non-Polish people.

It made me laugh knowing Mr. Zukowski’s joke was on us Poles. As I rode along, I thought someone like Mr. Zukowski wouldn’t care for Chopin. And, regarding my father, the joke was on me, on Stefanie—“Stefancha,” if you pronounce it the Polish way. I never wanted to admit my dad was slow, that he was confused by things. Once I acknowledged it, I laughed all four blocks to Sister Leokadia. When I arrived, I wasn’t laughing anymore, for she knew what was courageous and noble in a spirit like my father’s. Sister Leokadia knew everything.

As I walked across the school lawn, I could hear through the open gym window Sister practicing a nocturne, my father’s music. The nocturne was moving and sad—like Poland must be this night. As the music rose into the darkness, I wondered whether the great Chopin heard it in heaven, whether Dziadua and Mother heard it, whether Stanley “Car Wash” Karawinski heard it at home in our Polish kitchen. A laborer confused by things people took for granted, my dad’s only fault was he had to tell the stories most people didn’t want to hear. In doing so, he thought he’d make himself into someone he wasn’t. I hoped he’d forgive me for thinking this about him; but I am his daughter, Stefancha the storyteller, and maybe when accidents happen to me, a nocturne will express who I am, too.

Nocturne

Prelude

Polonaise

As I entered the St. Adalbert’s gymnasium and saw Sister with a rose for Chopin, I knew I’d remember how, to honor her, fireflies came out for the first time that summer. I also knew that, during this evening, I’d tell Dad the saying Sister Leokadia had taught us. “Never waste an opportunity to tell someone you love them.” I would bow to my father and tell him this in Polish.

Leave a Reply