Wired: The Short Times & Fast Life of John Belushi by Bob Woodward; Simon and Schuster; New York.

Bob Woodward is an aggressive journalist who has helped reveal the secrets of Supreme Court Justices and a president. Like his previous efforts, Wired is a best-seller full of gossip and intrigue. Excerpts have appeared in the Washington Post, New York Post, and Playboy.

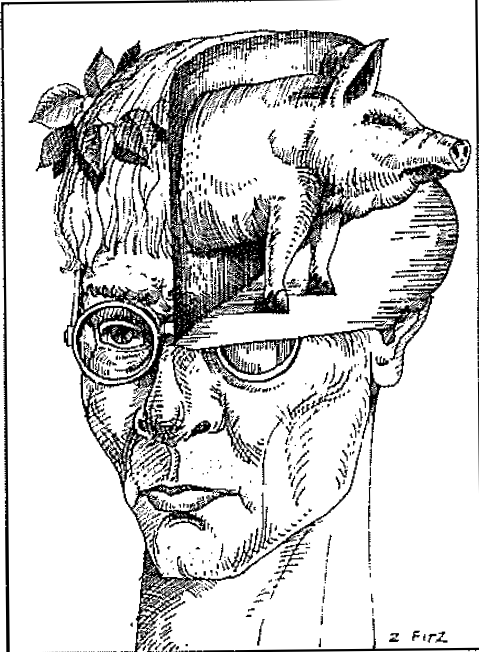

John Belushi found fame in I975 as a member of “The Not Ready for Prime Time Players,” the comedy troupe that appears on NBC-TV’s Saturday Night Live. He became more famous to the public through a series of (with the exception of Animal House) forgettable films. He became more famous to Holly wood through a social life that was driven by drugs and ended by drugs in 1982.

While Belushi’s life was not quite as short and fast as the title intimates, Woodward focuses on just a few essential aspects.Wired is not a biography that tries to trace emotional and psychological trends from childhood to the climax of a career. But where Woodward chooses to focus he examines with diligence. Wired contains so many facts about what Belushi did and where he did it, that if Belushi had lived he could not have delivered a more detailed account.

After a brief profile of Belushi’s high school years in Wheaton, Illinois, where he was cocaptain of the football team and the school’s best actor, Wired depicts his climb to national stardom. The mercurial actor distinguished himself in improvisation shows in Chicago, earning rave reviews from city newspapers. This was the early 1970’s. His wild appearance with long, frizzy hair and slightly bulging belly fit both the times and his temperament. In narrating this period, Woodward points to the start of Belushi’s drug use, also apropos for the early 1970’s. This, and not Belushi’s talent, emerges as the dominant motif.

Woodward, while maintaining the drug theme, does describe the years at Saturday Night Live and the making of several movies. Some intriguing points are raised. When Columbia Pictures was convinced that the movie Neighbors would be a disaster, producers adopted a hit and run strategy—releasing the film just a few days before Christmas, hoping to hit the big market and then let the poor picture die. Their strategy proved prudent, for the film was a loser.

Self-indulgence causes trouble in Hollywood. Movie budgets are often said to be inflated to cover drug purchases, and when a star cannot control his appetites, he can subject an organization to strange pressures. Woodward recounts one incident, when Belushi arrived at director Louis Malle’s office demanding to see a script:

John kept thrashing about . . . sweating as if there were a flame under him. Word was being spread … that John was there, and people from some other offices popped by to see him or hang around outside. . . . It was like Mardi Gras and all of a sudden a John Belushi float had entered the room.

Woodward is so confident of his research that he does not hesitate to tell the reader who in Hollywood takes or sells drugs. Jack Nicholson and Robert De Niro are on his list of takers—which might explain some recent flops.

Obviously, the real story is not just John Belushi but drugs, psychological instability, and Hollywood. Woodward only gets part of the story. Although Woodward is renowned for getting behind the scenes, he does not know what to do once he gets there.Wired has the facts but offers no more insights than a travelogue. And Woodward’s style is no more elegant or interesting than Belushi’s wife’s, if her diaries are any guide.

What was Belushi like, when he was not a Mardi Gras float? Why did he become a Mardi Gras float? At times Woodward tells us that Belushi could be endearing, but this seems unlikely. Woodward gives the impression that there might have been more to Belushi. The only hints are that Belushi would cry every few years when a friend would tell him to cut down on cocaine. Once he stopped crying, however, the habit would resume. According to his wife, he was the same about his weight:

John looked stuffed, his stomach like a giant, taut beach ball. Finally, she decided to broach the subject wouldn’t it be tough when he had to sing and dance hard for the filming? He agreed it would and said he wanted to do something to lose weight. But that night they went for a big dinner.

More surprising, we do not even discover whether Belushi was a genuinely witty, clever, or funny person. Woodward must have spoken to hundreds of people who knew him. But no one seems to have told the author that his main character had a sense of humor. Often it is difficult to judge whether a comic actor is a good comedian with an amusing wit or just a talented actor. Lucille Ball, for example, continues to credit her writers for the humor in I Love Lucy. Lucy may have been a good actress, but not much of a comedienne. Woodward does not adduce enough data to judge Belushi’s real talents. Belushi’s disdain for writing might suggest he was more an actor than a truly funny man. At first one might attribute Woodward’s shallowness here to his admitted ignorance of arts and entertainment. But these same questions should be raised in Washington, where Woodward is more at home. Even The Brethren questions whether Supreme Court justices write their own opinions.

For Woodward the most important question seems to be, Why didn’t anybody stop Belushi’s self-destruction? Responses from friends and acquaintances in Hollywood and New York are unconvincing: I thought he’d outgrow it; I didn’t know how bad it was; I didn’t know him well enough; etc. Although Woodward is too objective to weigh the merits of these excuses, he does find it sad that so many people knew of Belushi’s problems but did not take firmer action. His agents felt torn between acquiescing to his demand for drug money and turning him down—which might put Belushi in even worse trouble. One might question, though, the sincerity of remarks from people who had knowledge of the drug habit. No one, it seems, was willing to admit that he or she happily supplied Belushi with drugs. But some people must have. Belushi was not a lone junkie lost in California. He was part of a fast Hollywood crowd, working in an industry where cocaine was often as vital to a movie set as a camera.

Some of the apologiae for inaction sound plainly silly or contrived. A few months before Belushi died, he offered Saturday Night producer Lorne Michaels cocaine. Michaels hesitated, Woodward writes:

To refuse would be to appear to judge John, to stand above him. What good would that do? There had always been, always would be, a cultural gap between the two. Not just because Michaels had once been the boss, not just because John was now infinitely more famous and powerful; not just because Michaels was private about his own drug usage and John almost hysterically public about it. But John was reaching out, and the two had shared a lot.

Michaels took a little cocaine.

Although Woodward talks a lot about drugs and about Hollywood, his approach is not sophisticated enough to ask why so many people in Hollywood use drugs and why so many people out of Hollywood do not care whether their heroes are performing under the influence of narcotics. Indeed, many of Belushi’s funnier moments on Saturday Night were monologues about drugs during news report parodies. Richard Pryor’s near fatal accident with drugs has provided him with many new jokes but few new thoughts about drug use. A movie star or starlet might become an addict or alcoholic because of emotional or psychological disorders. Yet, there are some who see drugs as a recreational tool. To them, drugs are fun. How long they can contain their usage is another issue. We do not know why Belushi began using drugs, or why he continued, or why he could not stop or be stopped. Woodward seems to blame a stilted family life, in particular Belushi’s rather. But all that Woodward could find about Adam Belushi was that he worked holidays and was Albanian. Neither hardworking fathers nor Albanian fathers necessarily cause drug addiction, at least as far as it is reported in the medical literature.

The more fascinating question con cerns our response to famous people who are drug addicts. Many people are more tolerant of celebrities taking drugs than they are of commoners using drugs. As Albert O. Hirschman points out in The Passions and the Interests, people used to believe that only royalty had the capacity to feel real passion. In literature their trials and experiences were metaphors for entire nations. Tragic heroes, according to Aristotle, had to be of noble rank. The common man could not face real tragedy. The point is that stars, many feel, are entitled to drug and alcohol use, because they have the capacity and the need to go beyond the natural, normal lives most of us lead. They are royalty. Like Henry VIII they have big appetites for food, sex, liquor, and adventure.

When the Judy Garlands, Mario Lanzas, and John Belushis of the world are destroying themselves, tearing their minds and bodies down, some think the stars are just living it up—as they would if only they were “great” men, if only they had the “lust for life.”

I do not know whether Belushi would have been a drug addict if he had not made it to Hollywood, if he had taken over his father’s restaurants instead. But I do know that no one near would have tolerated him or his habits. And he might not have tolerated himself either.

Maybe there cannot be classical tragedy among the middle and lower classes. Surely, though, the upper class can be just as pathetic as the rest of us. And we should not mistake their pathos for passion.

Leave a Reply