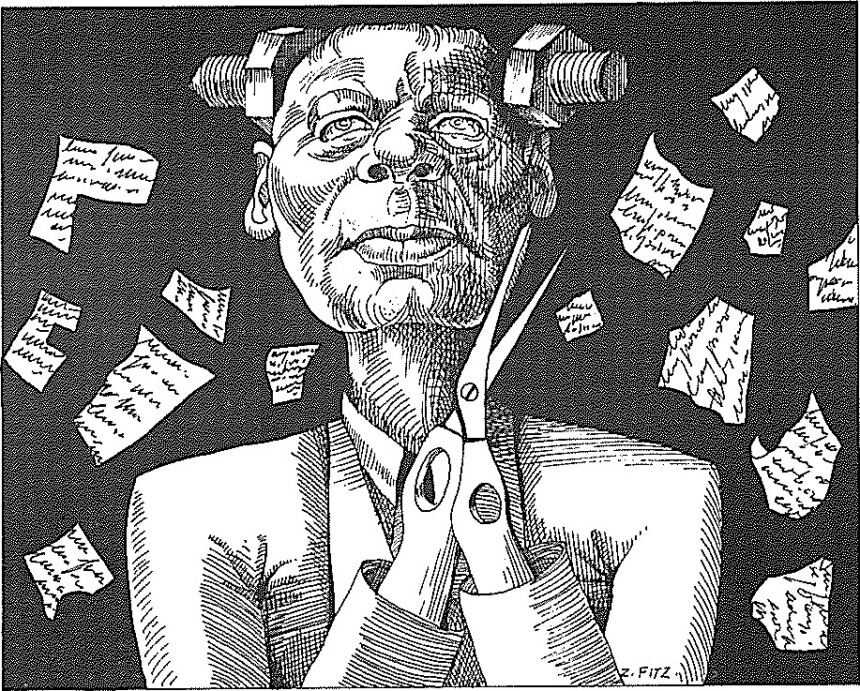

Malcolm Bradbury: Rates of Exchange; Alfred A. Knopf; New York

Vassily Aksyonov: The Island of Crimea; Translated by Michael Henry Heim; Random House; New York.

Signs of massive political fatuity abound. In the face of more than a decade of relentless Soviet arms acquisition, righteous notables in the West chant for a (virtually unilateral) freeze on our nuclear weapons with a disregard for consequences that could make us wish for the days of “Better Red Than Dead,” when at least some price for weakness was implicitly acknowledged. Television news programs now solicit the opinion of Tass apparatchiks as if these men were journalists expressing their own considered analyses of events. Presidential hopefuls strive to outbid one another in proclaiming how many lands they would not defend against enemies of this country. All this seems more than routine silliness: the suspicion grows that many in the West no longer can conceive of a world in which we confront an unyielding rival power seeking the peace which comes with absolute mastery. Or, if genuine foes do exist, so the thinking runs, they surely must be susceptible to the enchantments of “communication” or, failing that, to the sanctions of so-called ”world opinion.” Moreover, many appear not to recognize in the West any values worth defending at more than a nominal cost. Together these attitudes generate a weightless solipsism which denies the fearful and enduring divisions of most of this century.

Two recent novels deal unflinchingly with the profound and enlarging gap between what, on the one hand, much of the West wishes to believe about the Soviet Union and its satellite states and what, on the other, constitute the implacable dynamics of totalitarianism. Indeed, English writer Malcolm Bradbury’s Rates of Exchange and Russian exile Vassily Aksyonov’s The Island of Crimea share numerous similarities. Both novels treat international intrigue in a largely comic mode, creating an unusual blend of adventure, suspense, satire, and occasional pathos. Each novel, furthermore, has as its central character a figure marked by a disquieting hollowness that appears a symptom of our age.

Malcolm Bradbury’s Rates of Exchange is less overtly political: a (some times sad) comedy of the cultural exchange visit of one British linguist, Professor Petworth, to an unnamed country in Eastern Europe where he aspires, vainly, to do nothing more exciting than be a way from his burdensome wife and give a few canned lectures. But the middle-aged, thoroughly bourgeois professor encounters more than the frustrations he has come to expect as a jaded “cultural traveller” the delays, the mixups, the occasional official bullying, and the constant mispronunciations of his name (as Pitwit, Pervert, Petwurt, and the like). Two women, one his official guide and the other a fascinating novelist, seek to lure him from his academical half-life into a confrontation with a reality fuller and more dangerous than exists on thepath from lecture hall to faculty lunch to cocktailparty. To travel from theWest to a Soviet-dominated country is not, after all, to visit a place distanced only geographically where the people are “really just the same when you get to know them.” Decades of Party control have generated deep and painful distortions in the patterns of human feeling and action. These differences and the system behind them, both of which Petworth is temperamentally inclined to ignore, form the dark backdrop to the tribulations of the bumbling professor.

Two related metaphors structure the contrasts of West and East. One, appropriately, turns on language. The other also involves transactions, financial this time rather than verbal: it is the rate of exchange of the novel’s title. Bradbury skillfully develops the permutations of both figures without letting either become merely clever. Through both the reader comes to perceive clearly what our day’s version of Sterne’s sentimental traveler would wish away thetruth that the physical and mental walls built by communist despotisms are not to be easily demolished by gushes of “interpersonal communication.” Two centuries ago Sterne’s Parson Yorick could travel France without a passport (despite the hostilities between that country and England), overcome cultural impediments, and achieve emotional “connections,” however tentative and ambiguous. As Petworth’s journey shows, ours is a more complicated and harsher time.

Language, for example, raises barriers more daunting than those causing the book’s amusing malapropisms and double entendres. There is the formidable “grammar” of military control evident in the line of armed soldiers at the country’s only commercial airport. Indeed, in this land of pervasive censorship and suspicion, words themselves have a different weight; an airport inspector handles Petworth’s worn and harmless lectures as one would a potentially lethal package that might hold a bomb. The inescapable bugs, hidden cameras, and informers distort private and public speech; and, in so doing, they attack each person’s very selfhood. Words, therefore, are precious, and language becomes a battlefield as the regime overnight replaces one dialect with another as the new “official” tongue. Behind the ensuing riots ia a passion to retain some hold on the past, the local, and nonpolitical, a passion the reverse of the cultural and linguistic rootlessness implicit in Petworth’s standard lecture on “The English Language as a Medium of International Communication.”

Similarly, the otherness of the communist state manifests itself not so much in the chaos of the country’s five rates of currency exchange as in the prices the system exacts for activities, likewriting, which to us are comparatively free. Marisja Lubijova, Petworth’s lively and protective guide, pays with mindless orthodoxy for a job which lets her on occasion escape some of the drabness of the people’s paradise. For the bewitch· ing Katya Princip to publish her books the cost is steeper yet, involving complex measures of self-abasement and betrayal. The artists and teachers dutifully parading on the National Day of Culture are also bartering a portion of dignity in return for some security and the opportunity to practice their profession or create art, in however circumscribed a fashion.

Yet for all the grim bargains they have had to make, it is the women who possess a reality Petworth lacks and which they try to give him. Petworth, described as a man who had “not much soul to start with,” resists living more fully; in fact, he scarcely seems capable of so doing. The professor may strike readers as an academic counterpart of ]ohn Le Carré’s ashen-souled George Smiley; but if Petworth’s spiritual anemia is to be taken as having representative significance, it is not as a sign of Cold War burn-out but as a symptom of what the author elsewhere in the novel suggests is the “provisionality” of the West in contrast to the East’s solidity. In any event, Petworth creates only limited interest or concern on the reader’s part. Despite the journey filled with jolts to his inveterate complacency, he returns to Heathrow a man who, in several senses, has “nothing to declare.” Since his capacity for suffering appears limited, our sympathy goes to those who characters who remain behind in a land whose otherness has touched only slightly the sensibilities of this lightweight traveler.

Against a background of fast cars, luxurious living, double agents, and high-stakes international maneuvering, Vassily Aksyonov’s The lsland of Crimea explores more directly the theme of the failure of will afflicting the West. Aksyonov’s first novel to appear since he came to this country in 1980 has as its imaginative base the premise that the Crimea is an island, instead of a peninsula, which the White Army held against the Red in the Revolution and which has developed into a wealthy and free capitalist showcase in the shadow of the U.S.S.R.—in short, Russia’s Taiwan.With this fictive postulate, the book could easily have become a thin political fable, but Aksyonov creates a detailed and believable setting in which recognizably contemporary currents are modified in ways appropriate to this fictional land. Generating the novel’s action, for instance, is a movement for reunification with the Soviet Union called the Common Fate League, an entity headed by the book’s main character, the dashing, liberal newspaper publisher, racing car driver, and celebrity, Andrei Luchnikov. The movement is no simple stand-in for, say, unilateral disarmament; for part of its appeal is a complex longing the Crimeans feel to be part of their mother country, even a guilt at having escaped the horrors communism has inflicted on her. But in the dilettantish liberalism of Luchnikov, in his father’s stalwart dignity, and his back-packing son’s radical agitation for the rights and the (nonexistent) culture of the island’s older “Yaki” population, we recognize analogues to the situation in the West.

The book’s clarity of focus, unfortunately, does not equal its vividness of setting. A conflicting mix of subgenres contributes to the novel’s sense of diffusion; such is the blend of comedy, political intrigue, and satire that, not quite knowing what sort of book he is in, the reader does not take seriously enough the dangers either to the protagonist or to the island itself. Although there are a number of well-drawn characters (one of the best being a Soviet diplomat who cannot believe the Crimeans are seriously contemplating giving up their autonomy), their very profusion in this fairly short work detracts from a sense of direction. Not until the international race car rally in the late chapters does the novel regain its initial momentum. Nor does the main character sustain excitement. A play boy who is boring and egocentric, a political figure without intense ambition or conviction, Andrei Luchnikov emerges as something of a classy poseur, a man heading a potentially suicidal movement simply because it is fashionably contrary. There exists at the core of the man a nullity which makes it hard for the reader to care much about his fate; worse, his superficiality invites us to lose track of the stakes involved in his trendy, self-righteously foolish cause. (Again, as in Bradbury’s novel, it is a woman, here Luchnikov’s compromised Soviet mistress, who has a depth missing in the leading figure.)

The indistinctness of the novel’s protagonist may result from the author’s disturbing vision of the West as being so fundamentally self-preoccupied that it cannot come to terms with even the most dangerous forms of external reality. His treatment of television’s ability to to trivialize to the level of gossip even national catastrophe suggests as much; it has the wit and bite of the satire of a writer who comes fresh to our culture from one where they play for keeps. Equally insightful is Askyonov’s portrayal of the Common Fate League (whose acronym in Russia is SOS). The League’s appeal combines snobbish guilt over the island’s prosperity with a self-congratulatory, semireligious notion of the Crimea becomming a leaven which will altyer the direction of the Soviet Union. Adding to the mix is a fake realism about the consequences of the merger, as Luchnikov’s Courier runs pieces exposing selected and not especially horrendous shortcomings of the Soviet system; such hints of darkness have the effect of a dare, making the public more willing to embrace the challenge. The most powerful ingredient in the League’s appeal, however, is the sheer inability of the island’s comfortable population to believe that this movement is not just another routine political spectacle, a media event, which will in the end not disrupt the pleasing rhythms of their affluent lives. Things, they feel, will go on nicely; arrangements of some sort will be worked out; somewhere there must be insurance coverage against genuine national disaster.

In theme, tone, and structure, both Rates of Exchange and The Island of Crimea attempt to reflect the crazy quilt nature of attitudes in the West toward the continuing superpower struggle. Within the weakening in the West of what is now derisively tagged as the “Cold War mentality,” no single pattern of thinking has come to dominate. An older realism, somewhat muted, continues; leftist revisionism has achieved some status; more prevalent than either, however, may be the indisposition to think seriously, if at all, of the conflict whose we were once willing to face, whatever our political views. Now we ignore it, wish it away, or deride it as antiquated. The problem for both novelists is to embody mass vacuousness in characters who, if they are to be more than satiric targets, need to have an intellectiual and emotional richness which the authors see as missing from the contemporary picture. To write of a triviality of spirit without creating trivial main characters who lose our interest is the difficulty neither Bradbury nor Aksyonov fully solves. But both have captured an important dimension of our situation and in so doing have created enjoyable and worthwhile political novels. Since in each fiction the laughter, the cocktail party chatter, and the trendy poses halt in pain before the realities of regimes which have changed little in decades, we must hope the authors have not also given us works which prove prophetic.

Leave a Reply