The problem of evil has confounded humans throughout history. Philosophers and theologians have perennially constructed systems and myths to assuage the perception of the contingency of life. Religious belief, at least in Western civilization, usually filled in the gaps between the “ought” and the “is” that conflicted in the minds of those affected by the calamity caused by natural evil, or so-called acts of God. For Jews and Christians, Original Sin and the break it caused within the moral order also disrupted the natural order; this concept provided a systemic understanding of why evil exists. For Christians, the Resurrection is the proleptic fulfillment of mankind’s hope that the moral “ought” is on its way to rectification, making life bearable. With the Enlightenment, however, the world became disenchanted. It relied on science to solve man’s problems, and, when this failed, philosophers eventually accepted the futility of existence and proclaimed the death of God. For postmodern men, neither traditional belief nor “modern thought” is acceptable, according to Susan Neiman. She contends, rather, that both solutions fail to satisfy the man who wishes to know not only why evil exists but how to control it.

Neiman identifies two crises in history that reflect breaks with the dominant worldview of the time. The first was the metaphysical disconnect between human behavior and so-called acts of God, Who had previously been believed to control the natural realm, effecting good or ill in response to human behavior. The second denied moral evil, when philosophers could no longer discover the necessary human intention in the perpetration of human evil acts, e.g., murder, theft, adultery. Neiman dates the first of these dislocations from a 13th-century earthquake that devastated Lisbon and for which, despite the accusations of the clergy, the reprobate King Alfonso refused to take responsibility. The second, she believes, was produced by Auschwitz, where “the banality of evil” seemed to negate evil intentions and, therefore, responsibility for the consequences of evil actions.

Inspired by the cataclysmic events of September 11, Neiman challenges the Kantian dualism that separates the ideal from the real world. She also shows that the pessimism of Nietzche and Freud is contrary to human experience. Neiman posits instead a theodicy of hope, which she believes is constitutive of human experience and necessary for human survival. For her, September 11 was an apocalyptic moment. The truths to be learned from it, she believes, are essential to understanding the precariousness of contemporary human life and to making life more intelligible and more secure in the future. Neiman sees the events of that date—whose causes and damages so resembled the destructiveness of nature (acts of God) but were nevertheless born of human intention—as the rejoining of metaphysical and moral evil.

Although Neiman does not posit a transcendent source of meaning for the world, she seems to move in the direction of a “god within humans” who may now, through a shared will for a more just and humane world, construct the reality of it. While this is not the stuff of religion, it does reintroduce the idea that there is more to the world than meets the eye. Besides achieving a wonderful exposé of the inadequacy of modern thought from Kant to Rawls, Neiman’s book provides the reader with useful insights and a reinforced faith in humanity. The acceptance of nonscientific truth by postmodern philosophy may lead some to go further in searching out the root of those myths that give structure and meaning to life. Here, Christianity remains a realistic possibility for a world in search of hope. Certainly, Neiman’s book will give, short of faith, a glimmer of hope for those seeking to comprehend the tragedy of September 11.

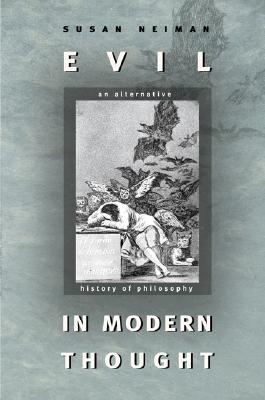

[Evil in Modern Thought: An Alternative History, of Philosophy (by Susan Neiman Princeton: Princeton University Press) 358 pp., $29.95]

Leave a Reply