Writing—literary creation in the fullness of the sense that we have known it in the previous century and even in the one before, from the French and Russian masters, the daft Irish, the mad Yankees, the haunted Southerners (and from elsewhere, of course)—sometimes seems to be on the way out. Senses of language, of irony, of place, of reality, appear to have been dulled or even eradicated by education and cable television. Contemplation does not square with institutionalized victimology, nor does listening jibe with noise. Or, as a thoughtful man put it the other day, “American literature is over.” “It’s not over,” I replied. “Maybe it’s just that Americans aren’t writing it any more. I can’t remember what Edward Said said, but Yogi Berra said, ‘It’s not over till it’s over.’”

From what I can perceive from these collections of short fiction, there is a certain identifiable quality that emanates. The Shape of a Man includes the story “Laissez Faire Redux,” in which the first thing that springs to mind today when you say “South Carolina” is treated fictionally and dramatically and humorously, not politically or ideologically. The question of flying the flag, or which flag, is resolved in a demonstration of the shared Southern culture known to both races in their familiar history, music, and flag—a point easily understood by those who know a culture from the inside and baffling to ideologues who do not. That is much, but even better is the first paragraph: “It was a mistake to get cable television, just like it was a mistake to get a brother-in-law, because when you put the two of them together, there is no peace for me.” Such a sense of voice tells us that we will hear a story, not a diatribe.

The next story in that volume is set in Manhattan, as a man tells a story about how his perception of a socialite changed. And the next is narrated by a woman of a certain age, the fourth by a younger one, as both confront erotic challenges. The novella, “The Shape of Man,” a gothic tale of violence, is set in the 1950’s. The last story, in the third person, concerns a woman who memorializes her son, dead in World War II. In short, we see from Randall Ivey various angles of attack: different decades, classes, sexes, and tonalities. Ivey seems to be attracted to obsessed personalities, and he adjusts his language effortlessly to whatever the requirement might be.

The stories in The Mutilation Gypsy are even more varied. Two ghost stories, “Son” and “The Book and the Computer,” are so different from each other in diction, tone, and conception that we would be hard-pressed to know that they were written by the same author. “The Present Unpleasantness” is a satirical treatment of contemporary South Carolina that has little in common with either the experimental “Sunset” or the fable “Appassionata.” The title story recurs to the realm of the Southern grotesque and the traditional subject of growing up through experience. As a collection, The Mutilation Gypsy shows that Ivey can do just about anything and that he finds inspiration all around.

This author has declared that his work has a center, that it derives, even in variety, from an identifiable location.

Most of these stories . . . are grounded in very familiar environs, the South Carolina upcountry, where I have lived, save for my college years, practically all my life. Early on I set out as my life’s work the depiction of my fellow upper Carolinians in a cycle of short stories and novels set in the apocryphal Compton County, a cotton mill town of my own imagining, populated by mill hands and farmers and bankers and preachers and politicians both honest and suspect and academics and illiterates and poets manqué and renegade movie directors and transplanted Yankees and scalawags of all sorts and young folks striving to get out of their home country or remaining and trying to make sense of it and old folks who have not yet settled down to enjoy their twilight years but are still pursuing life with fierce appetites.

Ivey’s declaration makes sense as an introduction to his work and also as a response to the experience of it.

Randall Ivey, who professes writing and literature at the University of South Carolina at Union, has, in all probability, developed views on the state of writing today. Even so, his practice is itself quite a statement about the craft and the possibilities of writing—one that says, among other things, “It’s not over.” Randall Ivey is among those few so possessed by vision and word and voice that he might say with Flannery O’Connor’s Hazel Motes, “They ain’t quit doing it as long as I’m doing it.”

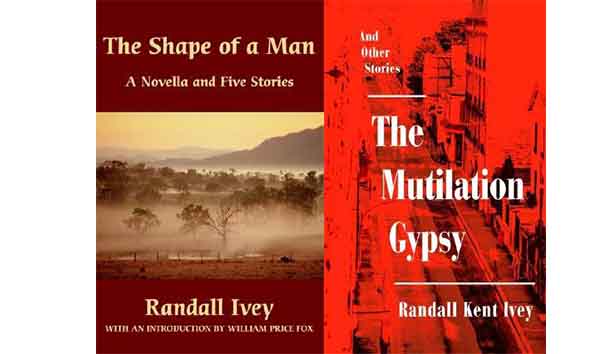

[The Shape of a Man: A Novella and Five Stories, by Randall Ivey (Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, Inc.) 121 pp., $10.95]

[The Mutilation Gypsy and Other Stories, by Randall Ivey (Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, Inc.) 157 pp., $13.95]

Leave a Reply