“Literature is news that stays news.”

—Ezra Pound

George Garrett is a man of letters—a member of a diminishing breed that may soon vanish. For well over three decades he has regularly published poetry, criticism, and fiction long and short; he has also written screenplays and memoirs, and explored still other modes. This very facility as a writer of poetry and prose has somehow prevented him from receiving sustained attention and consequent rewards from the critical establishment in this country, especially the East, that he has deserved for a long while. This is not to say that Garrett has been ignored, for that is not the case. He was honored with the 1989 T.S. Eliot Award from The Ingersoll Foundation, and other prizes have come his way. But on the whole he has not received his due as a writer, nor has he been sufficiently recognized for his manifold and profound service to the Republic of Letters, a service that extends beyond what he has written to the people he has taught and others he helped, the many books he has edited, the dozens of projects he has nurtured.

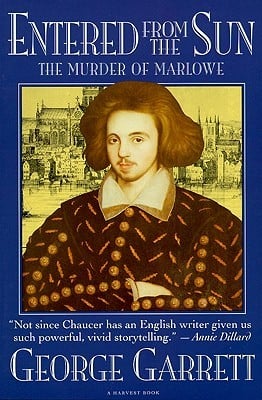

Perhaps with the publication of Entered From the Sun this sad state of affairs will be altered to the good. Certainly Garrett has carried out his responsibility to his craft and to the reading public and has earned the praise that this novel is beginning to receive and that it richly deserves. And just as certainly he is first and foremost a novelist.

Entered From the Sun is the last novel in Garrett’s Elizabethan trilogy, a glorious work that began with Death of the Fox (1971) and continued with The Succession (1983). The first novel culminates with the execution of Walter Raleigh in 1618; the second, in the death of Elizabeth and The Succession of James I in 1603. The present novel centers on the events surrounding the murder of Christopher Marlowe in 1593; its action chiefly concerns the last year or so of that same decade—the end of the 16th century. We discern that the novelist has been steadily moving backward in time, but the period covered by the three novels, especially The Succession, runs from the birth of James in 1566 to his death in 1625. The three novels therefore extend over a considerable sweep of history but at the same time are focused on dramatic events that unfold in relatively short periods of time.

As Monroe Spears brilliantly demonstrated in “George Garrett and the Historical Novel” (Virginia Quarterly Review, 1985), Garrett has pushed the historical novel as a form to its limits but at the same time not been bound by the perceived limitations of that form. He has neither written popular fiction in this vein—that is, costume romance—nor has he allowed himself to be cribbed, cabined, and confined by the facts of the period as they can be ascertained through documentary evidence. Yet he has stayed within those facts—and not given himself the free rein of the costume romancer to career through history and trample it.

The facts concerning Christopher Marlowe’s death are precious few, and that death will always be mysterious. That he was the Muses’ darling, as his contemporaries, especially his fellow poets and dramatists, thought; that he was probably a homosexual and an atheist and a spy as well, not to mention an extraordinarily difficult, contentious, and hot-tempered man are matters hardly open to dispute. Marlowe, Garrett believes and makes us believe, was murdered by agents of Sir Francis Walsingham, a patron of the arts who also created England’s first professional secret service and thus helped defeat the Spanish Armada by indirect means. Marlowe was on Walsingham’s payroll and perhaps refused his orders, with the result that his service and life were terminated.

The plot of Entered From the Sun turns upon Marlowe’s death. The leading characters of the novel—Joseph Hunnyman, a minor player in the theater and a petty confidence man, and Captain William Barfoot, an adventurer and soldier—are hired by rival shadowy organizations to investigate Marlowe’s death and to seek new evidence and determine what was involved beyond an apparent tavern brawl among drunken acquaintances.

The engine driving the action of Entered From the Sun is one of the oldest in literature—the detective plot. Think of Hamlet, Bleak House, Crime and Punishment, and many another classic in which the action is powered by the reader’s wanting to know the simple—and yet endlessly complicated—facts of a dazzling crime (often, as in this instance, murder). It is a dramatic situation fraught with possibility and worthy of our fascinated scrutiny.

This plot leads the reader into the rich world of the Tudors, a world previously dramatized to such good effect by only one other novelist—Ford Madox Ford (in his Fifth Queen trilogy, which deals with Henry’s reign and concerns intrigue in all its guises). I mention Ford for several reasons: Garrett has Ford’s easy command of the idioms of the time and his same ability not to fall into mimicry or burlesque or archaism while forging a style appropriate to the period and at once modern—contemporaneous, not contemporary, we might say. Garrett also has Ford’s singular ability to use real people as leading characters, but he creates a wider range of fictitious characters to people and move his action. The principal historical figure is, of course, Raleigh, who appears in a brilliant scene toward the end of the new novel—and on the eve of Barfoot’s departure for a campaign in Ireland. It is there that we last see Barfoot: he is surrounded by Irish irregulars and fighting for his life.

In contrast Hunnyman, who in terms of simple poetic justice has much less right to a long life than Barfoot (who has survived many a scrape during his honorable service), lives to be an old man. Such are the whims of the world, the chances of Dame Fortune (or the turns of Mutability), Garrett is saying—but not in his own voice. The action is filtered through the consciousness of Barfoot, Hunnyman, and still others; it is presented pictorially and scenically and through invented letters, actual quotations, and still other means that only a skilled writer who is saturated in the history (social, cultural, popular) of the times could possibly bring to bear with any substantial degree of authenticity. It is this authenticity that has been praised by such literary historians as Samuel Schoenbaum and O.B. Hardison, Jr., as well as by such critics as Monroe Spears and Walter Sullivan.

The reader of any of these three novels—which do not depend upon one another but which together constitute an impressive whole—immediately enters the world of everyday life in Tudor and Stuart England. You get a keen sense of how the mundane world impinged upon the ordinary Englishman who was struggling to make a life for himself and his wife and children and who might find himself caught in a web of intrigue involving religion or politics or both. In such a web Marlowe was caught, as was his erstwhile roommate and fellow dramatist, Thomas Kyd; and many another artist found himself faced with the loss of limb or life for sins real and imagined against the state.

Christopher Marlowe, whose poetry was generated by a fine madness and was often “all air and fire,” as Michael Drayton observed, remains a splendid poet and playwright. During this summer and last my wife and I have seen superb productions of Faustus and Edward II mounted and performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford. It is little wonder that various people from Marlowe’s time to ours have argued that he did not die in the brawl at the tavern in Deptford but lived on to write Shakespeare’s plays. Garrett is too shrewd to suggest such a thing, but he catches the essential mystery of the man’s life and death in this novel, which finally is only incidentally about the Muses’ darling and which ultimately celebrates the mysteries of the very uncertain life during this time of woe and wonder.

George Garrett has been contemplating this world for most of his mature life, and he nearly wrote a dissertation on it while a graduate student at Princeton. He did not, thank God, spend himself on such a puny assignment but instead wrote these fascinating novels and in the process recreated the Elizabethan world, the most complex and various by a large measure that English civilization has witnessed during its mighty history. Anyone seeking to understand that world—to experience the impulses that ran hot and cold in the blood and marrow of Englishmen great and small—will learn more of it from these novels than any source or book in history. This is history with a profoundly human dimension, fiction fortified by history—the world of the past coming to life in the present.

[Entered From the Sun, by George Garrett (New York: Doubleday) 368 pp., $19.95]

Leave a Reply