The author of these various pieces can truly claim that he has lived “a writing life.” George Garrett has been working—successfully—for decades as a novelist and short-story writer, as a poet, playwright, and essayist, and as an editor and satirist. But there is even more to the writing life, which Garrett does not fail to address in all the fullness, and sometimes fulsomeness, of its postmodern reality.

He views his subject from many perspectives: the personal (in accounts, such as his interview with Madison Smartt Bell, that demonstrate his mastery of the literary trade and his own processes of composition); the generational (“How the Cookie Crumbles: Note on a Literary Generation”); and, finally, in terms of personalities and individual achievements (the “Other Voices” of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Eudora Welty, Fred Chappell, James Dickey, Madison Jones, and William Goyen). Garrett’s breadth of coverage is impressive and satisfying, but there is a something more, an extra quality, that gives his pages a special lift. Exactly what that something might be should be known to readers of this journal, Professor Garrett’s “Cowboys and Indians: A Few Notions About Creative Writing,” having appeared in the May 2002 issue of Chronicles. In that essay, Garrett told some home truths about creative writing and the contemporary American university in a piece that was rejected by the Chronicle of Higher Education, whose editors did not approve of the opinions that they had solicited. They found indigestible his polite and rational account of the contradiction between the nature of creative writing and the demands of a politically correct bureaucracy. But George Garrett’s knowledge—as well as the honesty manifested in that statement—are not the whole of the X-factor that distinguishes his writing.

In discussing the duty of the storyteller, Garrett reminds us of Keats’ phrase for surprise in poetry: “a fine excess.”

To create something new and worthwhile, to surprise by “a fine excess,” question all stereotypes, good ones and bad ones, and the shadow assumptions behind them. Turn the full force of your own doubts and skepticism against the commonplace assumptions of your age and, most especially, against your own personal certainties and assumptions.

It seems to me that, in these pages as in others, George Garrett has done just that. He can remember when the parabolas of Hemingway and Fitzgerald and Faulkner seemed near and accessible, when

Being a writer then became going to war and living to tell the tale, going on safari and shooting lions and other big animals, skinny-dipping in the fountain in front of the Plaza Hotel, and living in a crumbling cobwebby old Southern mansion.

But now he knows, as he tells us, that the gap between the generations is bigger than it once seemed, and the writing game has changed more than a little.

Because of his achieved perspective and his ability to invert stereotypes, Garrett writes shrewdly about F. Scott Fitz-

gerald and effectively about Truman Capote, perceiving the artistic strength as well as the authorial self-mythologization coexisting in In Cold Blood. Recognizing distinction when he sees it, he celebrates the poetic craft of Fred Chappell and pauses to remark, as he places him in context, “One of the great problems we face in much contemporary American poetry is in its trendy insistence on a central core of unearned nihilism.” Garrett knows what to say, even in the face of lies and provocative absurdities, about James Dickey, separating the man from his work. In short, Going to See the Elephant is a valuable and enjoyable collection that speaks to the literary experience of the last two generations and to our present sense that something has gone wrong. But, like Vanessa Williams, I have saved the best for last.

“The best” is the ultimate extension of the principle of “a fine excess” or, perhaps, what we might think of as “negative capability.” Precisely because he is a charming gentleman in his own person, George Garrett the writer is necessarily someone else. And that someone else is sometimes “John Towne,” the persona of Poison Pen (1986), an irrepressible voice of all that is repressed. John Towne tells it like it is, usually lusting after the supermodel celebs he mocks and insulting Howard Stern for his ugliness. In these pages, John Towne addresses the students of the University of Virginia in a highly original and instructive manner hitherto unknown to the president and deans of that admirable institution. He rudely interrupts the discourse of Garrett’s essay, “When Lorena Bobbitt Comes Bob-Bob-Bobbing Along: The Sorry State of Popular Culture”—or perhaps we should say that Towne’s rude interruptions turn that essay into a dramatization of, rather than a statement about, the sorry state of popular culture. And in “False Confessions,” Towne bitterly complains about how Garrett has used him and abused him. The incursions of John Towne across the borders of discursive distinction and tonal probity are proofs—as if they were needed—that, when George Garrett addresses the writing life, we must be there to attend.

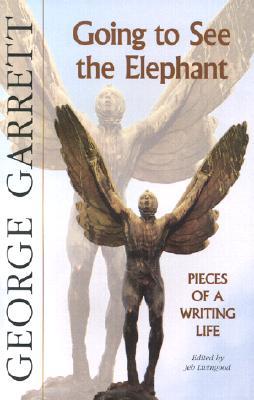

[Going to See the Elephant: Pieces of a Writing Life, by George Garrett; edited by Jeb Livingood (Huntsville: Texas Review Press) 195 pp., $18.95]

Leave a Reply