Eleanor Roosevelt and I go way back. My father taught me to read from a stack of her “My Day” columns in 1940. We happened to have a plentiful supply of “My Day” in the house because the doctor had refused to be responsible for my reactionary grandmother’s blood pressure unless she stopped reading it. I was at the stage when children discover the scissors and enjoy cutting things out of newspapers, so they named me official censor. Far from raising the blood pressure as her early columns so often did, the samples in this third volume, written between the triumph of Eisenhower Republicanism and her death in 1962, more often than not raise the gorge. There is enough banality here to choke John Chancellor himself.

Lauding the pacifistic outlook of the “Interdependence Council,” one of those starry-eyed fringe groups she could never resist, she wrote in 1956: “This organization may be only a candle lighted in a world which at present seems very dark to those who would like to see peace and goodwill established. But even a candle is better than no light at all, as many of us have discovered who live in areas where occasionally electric light is cut off for a time.”

On how to be rich without money: “One of the real gifts that brings you riches, I think, is the power of appreciation. If you can enjoy the blue sky, the beauty of the fresh snow, or the first green of spring, if you can hear music and have it leave a song in your heart, if you can see a picture and take away something that is real and vital to dream about for days, then you have the ability to get joy out of your surroundings. That kind of appreciation is perhaps more valuable than some more tangible kinds of riches.”

As ever, she is powerfully troubled by the tensions of our great cultural diversity that she did so much to bring about, but offers as solutions the platitudes of a chirpy headmistress settling a squabble over roommate assignments: “Whether the apartment next to you is occupied by a Greek or an Indian or a Negro or a Jew should make very little difference to you. My experience is that in New York City one sees very little of his next door neighbor, and unless you want to know him, you certainly are not obligated to make friends. But you are obligated to be courteous and to willingly share the facilities which have to be used in common,” she wrote in 1957. Two years later, the difficulties encountered by Harry Belafonte when he tried to rent an apartment in a white-only Manhattan building led her into one of those self-consciously noble and unconsciously funny Pollyannaisms that made millions of anti-New Dealers apoplectic: “I can think of nothing I would enjoy more than having Mr. and Mrs. Belafonte as my neighbors. I hope they will find a home shortly where they and their enchanting little boy can grow up without feeling the evils of the segregation pattern.”

Anticipating Martin Sheen and Robert Redford, her favorite entry in the 1958 Worid Day of Prayer was the invocation of Chief Yellow Lark beginning “O, Great Spirit.” In a 1955 column she beats the drums for the Thai “wai” form of greeting (palms pressed together in front of the body) over the Western customs involving physical contact: “I am not sure that they are not far better than our habit of shaking hands or the European habit of a gentleman kissing a lady’s hand. The latter may be a charming and pleasing custom to the ladies but may not be so sanitary.”

Mrs. Roosevelt wrote about whatever popped into her head, and there was very little that did not pop. Wisely, her editor has not even tried to arrange the columns in anything but chronological order, that being the only order they ever had. From Israeli kabbutzim to Cat On a Hot Tin Roof to “geronto-matriarchy” (her word for the control of American wealth by aging women) to lunch with Tito is par for the course. There are also pit stops at self-destructive romanticism, as when she plugs no-strings-attached foreign aid—”I feel somehow that agricultural surpluses are gifts from the Lord and it is not up to us to decide what shall be the political ideology of hungry people”—as well as an abundance of sheer drivel: “I do not know that Gandhi’s plans for living could be applied to modern life, but there is no doubt in my mind that the more we simplify our material needs the more we are free to think of other things. Perhaps what we all need to do is to sit down and think through how this could be accomplished without the loss of gracious living.” One Worldism meets the Junior League.

Although she was a member of the American aristocracy, she shrank from the aristocratic birthright of plain speech. The tone of her writing pulses with a cloying genteelness that makes her sound more like a socially insecure parvenu guided by the middle-class dictum, “If you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all.” Attending a performance of John Brown’s Body starring Raymond Massey and Tyrone Power, she explains laboriously: “I am frank to confess that I had not expected Mr. Power to give a performance which would satisfy me as this did.” Having said, in effect, that she considered Tyrone Power a mere movie star, she reverts to sweet nothingness: “I saw many of my friends, so that it was a pleasant social evening as well as one of great artistic satisfaction.”

The columns are full of these empty-calorie niceties, a few of which are unintentionally funny, such as: “I began to worry about getting to Pasadena in time for dinner and the evening meeting, remembering that the freeway between Los Angeles and Pasadena between five and six o’clock can be very crowded and very slow.” That was the night she met Sophie Tucker, who dropped what may or may not have been a bombshell into ER’s lap. We can’t tell, because ER either chose to ignore it or else she did not realize the significance of what Tucker said: “She came to meet me at the end of her performance, saying it was high time we should meet since she had known my boys for a very long time. She is full of life, and I could not help thinking what an extraordinarily vivid personality she has.” Very nice, but when somebody nicknamed the Red- Hot Mama says she knows all four of your sons, it is time to sit up and take notice.

Sometimes she knows perfectly well what she is saying, as when she adopts a mother’s hurt feelings to inculcate guilt in her son James when his 1959 book, Affectionately, F.D.R., showed her up as a bad nurturer. In his book James criticizes White House housekeeper Mrs. Nesbitt, “and in doing so, of course, in an indirect manner he criticizes me,” ER wrote tremulously, “for he does not seem to realize that whatever Mrs. Nesbitt did she did under my direction.” Such as using FDR arid her sons as guinea pigs for Department of Agriculture menus devised for the poor. It was at one of these Lucullan feasts that James asked her if he paid an extra nickel, could he have a glass of milk? His book, ER concluded nobly, expressed “the feelings of a very young man, perhaps at the time not quite capable of understanding certain things and who, therefore, was impatient.” James was 51 at the writing.

Her mask drops only once, revealing so thoroughly what she wishes to deny that one is almost embarrassed for her. The play Advise and Consent, based on Allen Drury’s novel, filled her with “complete depression and disgust.” It depicted “all the worst things that can be found in political situations that are brought about by the weakness of human nature.” She was especially upset by the portrait of “the man who is willing to lie because he thinks the ultimate good will be a justification. . . . It was a shock to see the office of the President included in the general downgrading of human beings who go into politics with legitimate ambitions but who are still weak, small, vindictive, determined to gain their own ends whether good or bad, and ruthless where anyone except themselves is concerned.”

She comes close to advocating censorship: “If this were wartime I think one would cry treason at this play.” After voicing conventional fears about what the play will do to “young people,” she calls for a positive, upbeat story about American politics to counteract the harm Drury’s will cause, and concludes, “I think perhaps the fact that the play is so well done is something to be deplored.”

The volume is not helped by editor Emblidge’s lavish adoration of Eleanor Roosevelt, which makes many of his introductions to the columns almost as cloying as the columns themselves. He is right, however, in his belief that there has never been a woman quite like her. She has many clones in the feminist movements past and present, but in the history of wives of heads of state, she can be compared to only two.

In her officious energy she recalls Philippa of Hainault, who took advantage of her position as consort of Edward III to become a career woman, importing her native Flemish weavers and starting England’s woolen industry between countless good deeds. And in her puritanical self-righteousness she recalls Mme. de Maintenon, morganatic wife of Louis XIV, who punished her pleasure-loving husband with her bans on overeating and sex.

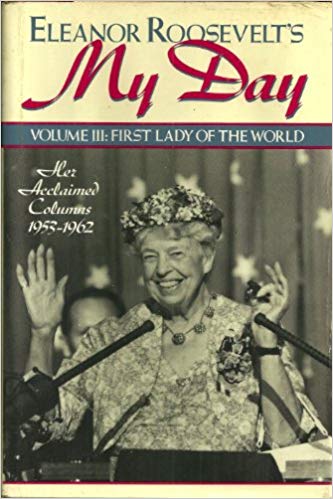

[Eleanor Roosevelt’s “My Day,” Volume III: First Lady of the World, 1953-1962, Edited by David Emblidge, Introduction by Frank Freidel (New York: Pharos Books) 361 pp., $19.95]

Leave a Reply