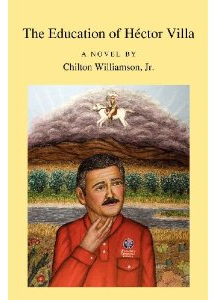

Henry Adams published his eponymous autobiography in the early years of the last century. Now, just about a hundred years after The Education of Henry Adams, we have The Education of Héctor Villa. America is center stage in both, but they are two very different Americas. The one Adams portrayed was on the rise and dazzling the world with its achievements, while the America of Héctor Villa (and of President George W. Bush) is no longer on the rise and no longer dazzling. However, it is waddling along—and pretty darn content with itself.

The Héctor we meet in the opening chapter of Chilton Williamson’s novel is also pretty content. And deservedly so. Like Henry Adams, a direct descendant of two U.S. presidents, Héctor has an illustrious family tree. He is a (collateral) descendant of Pancho Villa, who is, it might be argued, even more illustrious than any member of the Adams family. As honored as those Boston Brahmins may be in the United States, they are of little account in Mexico, whereas Pancho Villa is memorialized on both sides of the border. We are talking here about more than fast-food restaurants. We are talking about Pancho Villa State Park right near Columbus, New Mexico, where, in 1916, several hundred Mexican revolutionaries, led by Pancho Villa, killed 18 Americans. As magnanimous as Mexicans may be, it is doubtful their magnanimity would extend to naming a public park after a murderer of their countrymen. Chronicles readers know well the mordant wit of its senior editor for books, and that wit is on glorious display throughout this novel, but Pancho Villa State Park did not spring from Mr. Williamson’s imagination. There actually is such a place. Is it any wonder Williamson’s hero feels so at home in America?

Héctor Villa has more going for him than a distinguished pedigree. He is a success in his own right. He owns his own computer-repair business and is contentedly married with two very American children: a son named Dubya, in honor of the 43rd president, and a daughter named Contracepción, in the hope she will remember how to keep her honor. Further proof of his success is his house, which, though it would distinguish itself in any community in any part of America, is even highly remarkable in Mexican-American Belen, New Mexico. Héctor is especially proud when he gazes out his front window and surveys his “assemblage of art objects.” These include a miniature drill rig painted orange, yellow, and purple; a windmill nearly as tall as his house; and an old Army Jeep with sunflowers where the engine used to be. Also not to be overlooked are “ceramic confections” in which Adam and Eve and a serpent are grouped with various saints and animals. It is this art, so beloved by Héctor, that leads to his first run-in with the authorities, and the beginning of his education in 21st-century America. In a letter, the philistines on the town zoning board call his yard an “eyesore” and a “public nuisance” and tell him he has ten days to bring his property into compliance with public standards. Heartbroken and angry, Héctor obeys, but his troubles are just beginning.

Returning from a trip to Mexico for the annual celebration of the descendants of Pancho Villa, Héctor decides to save time and avoid the long lines at the international border crossing by taking a bumpy back-road shortcut. However, just after crossing the border he spots, 200 yards ahead, three middle-aged, heavyset men, each one armed and signaling him to stop. Fortunately, Héctor remembers how his hero, President Bush, had described the Minutemen: They are “vigilantes, extremists with dangerous opinions and un-American values.” He steps on the gas and drives straight for the paunchy activists, forcing them to scatter for their lives. “It was no more nor less,” the narrator tells us, “than what Dubya would want—and expect—a man in his position to do.”

While thousands, millions even, of Mexicans have crossed, legally and illegally, into the United States and garnered no attention from politicians or members of the media, following this incident both groups are attracted to Héctor. For the media, he is the journalistic equivalent of the perfect storm. Their victim-hero has dark skin and is a member of a downtrodden minority, while his would-be attackers are white-skinned, potbellied racist vigilantes. The incident also makes Héctor ideally suited for political exploitation. The incumbent Republican representative in Héctor’s congressional district has recently been killed in an auto accident, and a GOP bigwig calls with momentous news: President Bush wants Héctor to run for the seat. How could he say no to Dubya?

An utter political neophyte, Héctor brings nothing to the race but an eagerness to help his country, most especially its president, when it needs him and the advice of a drinking buddy even more politically clueless than he is. The support he gets from the state Republicans is not just clueless but damaging: The New Mexico GOP bestows on him a campaign manager who is president of the New Mexico chapter of the National Association of Paranormal Americans. One indication of how seriously he takes this position is his practice of distributing brochures from the International UFO Museum & Research Center during Héctor’s campaign appearances. Even these liabilities would not be insurmountable, however, if the New Mexico Democrats were to oblige Héctor with a lackluster opponent. Unfortunately, she is Tomasina Luna, who could instruct David Axelrod in the nitty-gritty of running a nasty campaign.

Even before Héctor declares his candidacy, Tomasina is relentlessly on the attack. Of course, his campaign manager is no help at all, unable even to draft a campaign speech (though he does twice offer the suggestion that Héctor should say Tomasina is from Mars). Yet, in spite of his opponent’s constant battering, for a brief period toward the end of his campaign, Héctor has hope, in the form of information—information he believes to be so devastating that it would take him all the way to Washington, D.C., and the House of Representatives. A Republican agent, posing as a journalist, has gained access to Tomasina’s computer and discovered that her screen saver is a most unflattering image of Vice President Cheney, wearing nothing but a Roman general’s helmet. (The most shocking feature is the negative impression of Mr. Cheney’s manhood.) All that Héctor has to do is to hold a big rally where he will release this truly scandalous development. Tomasina is going to learn that he, too, knows how to play rough.

Héctor, however, has underestimated his opponent. Just as he is on the point of unveiling her obscene screen saver, Tomasina brazenly interrupts the proceedings with a bombshell of her own: Héctor Villa is an illegal alien! For one of the few times in the campaign, she is not lying: Twenty years earlier, Héctor and his wife had snuck across the border with a party of Arabs, guided by a coyote. He fit in so easily, adapted so readily to the American lifestyle, that never before had his legal status been challenged, whether by his neighbors, his employers, or the Republican officials who pressured him to run for office.

Tomasina’s revelation brings Héctor’s political career to a quick and humiliating end: He will not, after all, be the first illegal immigrant elected to Congress. A lesser man, a lesser American, would have quietly gone back to his computer business and paid no more attention to the wider world. But Héctor is indomitable. As a private citizen (sort of), he is always on the alert to defend America—which is a good thing because, even in his own little corner of New Mexico, there is plenty to defend against. This includes his daughter Contracepción’s burqa-wearing English teacher, a Mrs. Ahmadinejihad from Iran, who has a weak command of English and a great hostility to America and her leaders. Contracepción falls in love with the dreamboat son of a Muslim cleric from Afghanistan who masterminds an attack on a prayer meeting led by Héctor’s preacher, Brother Billy Joe. And there are the jihadists who sneak across the border— an international corridor, not reserved for incoming Mexican invaders—and carry out attacks on, among other things, Héctor’s neighborhood taberna. Through these and other outrages and near catastrophes, he tries to maintain his trust in George W. But it’s hard keeping a faith no one else seems to share. The media and even the police don’t take any of the incidents very seriously. After fighting and losing so many battles, the sadder and wiser Héctor does what would have been unthinkable when we first met him: He returns to Mexico, to Chihuahua, where he was born. “Life here, Héctor knew, was good for the Villas.”

Unfortunately, it is also boring, and so it isn’t long before Héctor begins yearning again for America, where, unlike in Mexico, it is morning every day. The Héctor who crosses back to America is a changed man, nevertheless. No longer is he sidetracked by concerns that he is not doing enough to assist George W. in the war on terrorism. What matters to him now is what matters to the vast majority of his countrymen. After they recross the border, he and his family head straight for the city he considers the iconic American metropolis, the city that has everything he’d ever sought in coming to America in the first place: Las Vegas. Héctor’s education is now complete. He’s a real 21st-century American at last.

Kevin Lynch, a former articles editor of National Review, lives in Arlington, Virginia.

[The Education of Héctor Villa, by Chilton Williamson, Jr. (Chronicles Press) 212 pp., $29.95]

Leave a Reply