Charles Fletcher Lummis was born near Bristol, New Hampshire, in 1859 and received an extraordinary education at the feet of his father, Henry Lummis, an erudite Methodist minister. This homeschooling was so effective that, by the time young Charlie got to Harvard, he found that he had already read through its then-rigorous classics curriculum. Bored with his studies, he became a “campus prankster,” which led to outrageous behavior that occasionally resulted in suspension. The unchastened rebel finally dropped out in his senior year, but not before striking up a friendship with another strong-willed undergraduate, Theodore Roosevelt.

Following a short stint as a reporter for the Chillicothe, Ohio, Leader, Lummis decided to make a national name for himself after landing a job at the fledgling Los Angeles Times. In September 1884, Lummis—newly married to Boston University medical student Dorothea “Dolly” Rhodes—set out alone to walk from Chillicothe to Los Angeles. The “tramp,” as he called it, spawned widely reprinted newspaper dispatches written en route and, later in life, a book. The vagabond slept in railroad section houses, hunted antelope on the prairies, and crossed the Rockies in frigid weather. His 3,500-mile meandering journey took him four months. In Los Angeles, Lummis soon became the Times‘ overworked star reporter. Two years later, he suffered a breakdown that caused a temporary paralysis of his left arm and changed his life forever.

In 1886, Harrison Gray Otis—the mercurial publisher of the Times—sent Lummis to Arizona to cover the last phase of the Indian Wars, Gen. George Crook’s pursuit of Geronimo in the Southwestern borderlands. Lummis’s experience traveling with Crook and covering the Apache War only added to his love of the wide vistas of the Southwest. He had spent time in the New Mexico pueblos region while on his famous tramp and, after his 1887 breakdown in Los Angeles, returned to Isleta on the Rio Grande for an extended convalescence. Here, Lummis found his life’s work and a happier marriage.

He became a much-demanded freelance writer, contributing articles about life in the Southwest to national publications, including the Atlantic Monthly, the Century, Harpers, and such newspapers as the New York Tribune and the Los Angeles Times. And he began to write the books that made his reputation: A New Mexico David (1891), A Tramp Across the Continent (1892), and The King of the Broncos and Other Stories of New Mexico (1897), among others. At the same time, Lummis divorced Dolly—now a successful Los Angeles physician—and married Eve Douglas, a brainy local schoolteacher. Their courtship coincided with the gradual disappearance of his mysterious paralysis.

Lummis quickly went from poverty to prosperity, thanks to his demanding work ethic. A typical 20-hour day consisted of mounting a horse and exploring Isleta and environs—hunting, fishing, inspecting archaeological sites, chatting with resident Indians—then staying up all night to write about it. He took up photography to increase his cachet with editors by submitting photographs (a new innovation practiced by few writers at the time) to accompany his endless stream of freelance pieces. He was the first photographer to record the secret ceremonies of the Penitentes, an obscure Catholic sect scattered throughout New Mexico and southern Colorado. Each year on Good Friday, they met to reenact the Crucifixion, sometimes so realistically that one of their number died from the ordeal. Lummis’s pictures of the ritual—sanctioned by the Penitentes after diplomatic coaxing—appeared, along with a descriptive article, in Cosmopolitan in 1889.

Because of his connection with Isleta Pueblo, Lummis was active in Indian political affairs. He vigorously opposed—in courtrooms and in print—the practice of separating children from their parents and sending them to distant Indian boarding schools from which they were forbidden to return for vacations, cutting them off from family and their native culture for years. “Are the thoughtful of us so absolutely secure of the success of our civilization as to force it upon the unwilling?” he wrote. Later, Lummis’s old friendship with President Theodore Roosevelt enabled him to influence progress in reservation reform; finally, however, the Interior Department’s red tape hindered him more than Roosevelt’s executive tenure could help him.

Lummis is probably best known as the editor of Out West, first titled Land of Sunshine. Initially founded as a promotional publication for the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, Lummis’s tenure rapidly turned it into a first-rate monthly magazine of politics and culture, boasting such contributors as John Muir, John Burroughs, Ernest Thompson Seton, Joaquin Miller, and Jack London. In an American journalistic milieu that took its cue from the East, Out West was the first credible “Western” magazine. During his decade-long editorship, Lummis and his contributors took a clear-eyed view of the West that was free of dime-novel mythology. In his monthly column, In the Lion’s Den, Lummis tackled such national and international issues as American foreign policy in Cuba and the Philippines. President Roosevelt was an enthusiastic reader.

One of Lummis’s great passions—along with his wives, children, and work—was El Alisal, the small-scale stone castle he built near Los Angeles. His mostly solitary, part-time labor on the house occupied ten years of his life. He died of cancer there in 1928. Bill Croke writes from Cody, Wyoming.

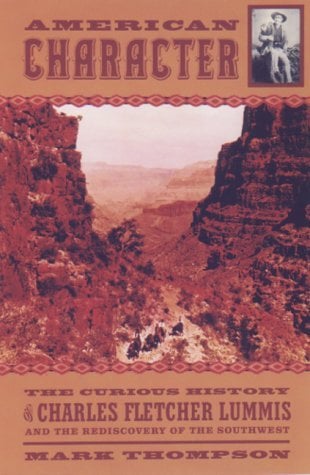

[American Character: The Curious Life of Charles Fletcher Lummis and the Rediscovery of the Southwest, by Mark Thompson (New York: Arcade Publishing) 372 pp., $27.95]

Leave a Reply