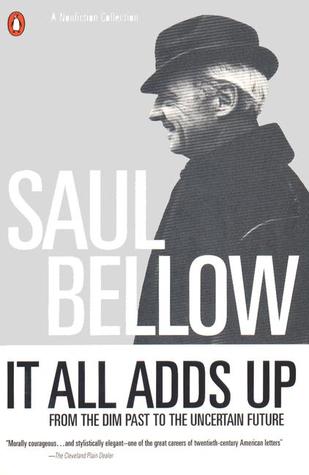

Saul Bellow’s It All Adds Up is his first (and given his age probably his last) collection of nonfiction. Mr. Bellow is close to 80. His introduction suggests a mood of self-reformation, not solemn but tending toward testament. He is said to be at work on a novel. He has outlived most of his generation, still cuts an agreeable and admirable figure among those pretending to literary accomplishment, and one wants to wish him well. He is now older than the Good Grey Poet and still hard at work.

The book consists of a redeployment of elegantly wrought magazine pieces, several self-ruminations called interviews, and shorter and longer memoirs, essays, and public lectures, arranged and cropped for maximum impact and concision though still long for my taste, taking in a considerable span of tumultuous life and literary history. If the life appears to me an exceptionally lucky one (and one gets the impression that Bellow may not appreciate just how lucky), then the history strikes me as ugly. Literature has been swallowed by “political statement,” ethnomania applauded into a ubiquitous vice, general culture (which in any case hardly exists) pumped up into the white elephant one got stuck with at the rummage sale of a nasty past; while any pretense to a settled outlook, a sense of moral splendor, or even mere talent is nowadays subjected to derision.

Bellow speaks with authority, having survived best-sellerdom, big money, numerous marriages and divorces, virtually all known literary prizes, celebrity status, the deaths of beloved fellow writers, and careful critical attention in the midst of the general collapse of serious literary publishing. Covering decades in dozens of pages, he commands fistsful of cultural histories and is unafraid to speak out, change his mind, and loathe his world.

Now perhaps it is time to say I never much cared for him. “Mr. Saul Bellow.” I can still hear the ring of that name in John Berryman’s voice. The poet and man of letters who had more influence on mv young writer’s life than any other living human being was in the habit of hitting his audiences over the head with his opinions like Odysseus clanging the flat of his axhead on a wooden dowel that would hold his raft together to just within sight of the isle of the Phaeacians. Nobody who came into contact with John Berryman’s view of literature could afford to ignore his high regard for the novelist Saul Bellow: “Mr. Saul Bellow . . . who writes . . . just a little . . . bit . . . better” (at this point an authoritative pinky would punctuate the air) “than anybody else!” But I wasn’t buying.

A modest mountain of novels offers a megalomaniac vision of the Jewish Alps. Warmly human it is; Tolstoy it is not. All the flaws of the Russian novel—a sort of discursive elephantiasis, the prose’s voice that of some epic fidgit drumming on the coffee table, improv, patter, one-liners, George Jessel mimicking Cervantes, Fielding, Twain, a little Plutarch, a coffee klatch intelligentsia blab—are reproduced in Bellow’s work.

Well. This would hardly seem the place to begin to explain all this, good reader—but. Deep in the works of Ortega y Gasset, he muses seriously on what he imagines Pericles would have said to my dear friend Hannah Arendt, had either of them been in a position to have experienced the existential anguish of Charles Chaplin in, was it, Hard Times . . .

I have to admit I made this up. But real passages from the published books, Augie March and Herzog, multitudes of them in almost any chapter, are in fact as compulsive as this: self-aggrandizing, flip, fundamentally noninterpretive wastes of print between “episodes.” Eventually, in spite of my reverence for Berryman, I concluded that Bellow did write only “just a little bit” better than, say, John Updike.

The creator of Augie old is, it seems to me, very much the consequence of the creator of Augie young. In the course of It All Adds Up, in his best interviewese, Mr. Bellow avers, “Well, what you call optimism may be nothing more than a mismanaged, misunderstood vitality . . . reckless spontaneity. . . I had found—or believed I had found—a new way to flow.” Though he calls himself “the cat that walked by himself,” Bellow walked, it seems to me, the corridors of the idiot optimism of the Jewish Marxist’s secular materialism, from the offices of the Partisan Review across the terrazzo of the Guggenheim Foundation, Bard Campus, The Village, into the offices of Commentary and the pages of the New York Times, biting a hand that always fed him rather well. Sounds suspiciously like lemming syndrome, if you ask me. This has been absolutely everybody’s broad highway, and it is taking every one of us with it over the abyss. Bellow himself, in one of the more daring public addresses of our whole pusillanimous period, put it this way:

I really don’t care to think about the inevitable succession of modernism by after- and post-modernism, I will grant you the “night of the world” and accept the fullest listing of the charges: emptiness of life, the unity of mankind on the lowest level, the increasing vacuity of personal existence, the victory of urbanization and technology—in short, the prevalence of nihilism, the absence of the noble and the great.

This may pass as a fair sample of “late” thought in the volume at hand, and if the view here is grim, it is also a true one. Many times. Bellow returns to Nietzsche’s hideous characterization of the insectile Last Man, to Yeats’s “The Second Coming” (“The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity”), to Wyndham Lewis’s pitiless indictment of modernity’s “moronic inferno,” accusing himself of having been “distracted by the subject of distraction,” and sometimes brushing against genuine profundities and knocking them over. Again, from the most recent of this book’s ruminations: “In no uncertain terms, Nietzsche tells us that the modern age concerns itself primarily with Becoming and ignores Being. And so perpetual Becoming preys on us like a deadly sickness.”

Perhaps the pursuit of Being is incompatible with the habit of holding forth? And perhaps Bellow has fleetingly glimpsed this? “On the other hand, silence is enriching. The more you keep your mouth shut, the more fertile you become.”

That this keeping your mouth shut was an ancient spiritual practice, “echemythia,” or Pythagorean silence, a five-year prohibition on the use of language intended to put the practitioner in contact with the life of the soul, as serious a matter for ancient Greeks as for ancient Hebrews, may not have occurred to Bellow, since Augie‘s one reference to Pythagoras—that he was killed over a diagram—does not appear to be the remark of an expert. But it could hardly have been unfamiliar to Nietzsche, the avowed enemy of Enlightenment Man’s “I think, therefore I am” way of defining Being. Nietzsche’s Last Man resembles a race of sand fleas hopping over its shrunken polluted world principally because the Last Man cannot sacrifice his beloved notion of The Self to save his soul. It is easier for the Last Man to declare that God is dead than that Marx and Freud were phonies. Just because Bellow knows enough to loathe the Last Man doesn’t mean he isn’t one.

This dilemma, which Bellow shares with practically everybody, shows its abysmal depths most dramatically in his bicentenary tribute to Mozart, a genius Bellow obviously loves. In spite of his own “hunch that with beings such as Mozart we are forced to speculate about transcendence,” he still comes out wrong: “When we say he is modern I suppose we mean we recognize the signature of Enlightenment, of reason and universalism, in his music—we recognize also the limitations of Enlightenment.” “We” in this case is a room full of Italian intellectuals, which is to say communists; an audience of a quality Mozart for all his putative modernity could never have imagined, an audience interested in the Don as an allegory for the capitalist class, in Figaro as The Worker, addressed by a novelist sincerely trying to stand up for lost dimensions of human nature—”the noble,” “the great,” as Mozart himself effortlessly embodied them—and walking a fine line between intellectual respectability and the absurdly simple truth.

Mozart is neither “modern” nor one in whom “we recognize the signature of Enlightenment,” by which the audience is expected to understand a historical tradition that begins with Descartes, passes through Trotsky, and ends with the computer revolution. But if there were indeed—and there is, of course—such a signature in Mozart’s music, it derives from those traditions of the soul whence the secularists filched this marvelous word “enlightenment” in the first place: Orpheus, Pythagoras, Plato, St. Augustine, Dante, the Christendom-cum-Classicism of the Renaissance that reinvented music around the theory of the numbers of the soul. Mozart was both devout and classically republican. His last work is actually, not metaphorically, transcendent.

Out of the Descartes-cum-Trotsky tradition came the Last Man, the Stock Exchange, MTV; also liberation theology, death camps, and tens of millions of corpses. If this tradition left its signature on anyone’s music, it is that of Schoenberg. It is time to stop congratulating ourselves on our deepest and deadliest confusions.

[It All Adds Up: From the Dim Past to the Uncertain Future, by Saul Bellow (New York: Viking) 327 pp., $23.95]

Leave a Reply