“Hail, happy Britain! Highly favored isle, And Heaven’s peculiar care!”—William Somerville

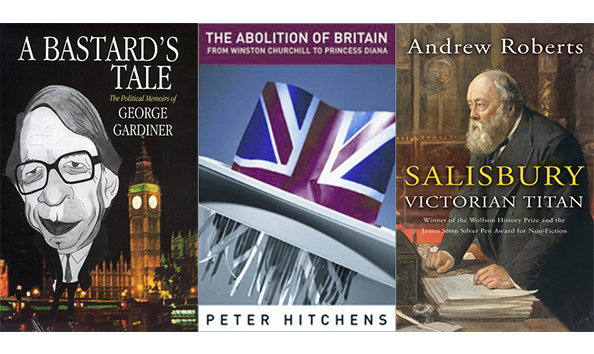

British conservative circles are awash with books at the moment. Apart from the usual think-tank reports and surveys, we have seen recently John Major’s and Norman Lamont’s memoirs, John Redwood’s Death of Britain, and the latest miscellany from Daily Telegraph columnist Michael Wharton (Peter Simple), to name several. Three books, however, are among the most interesting and useful of this post-May 1997 oeuvre.

A Bastard’s Tale is the autobiography of Sir George Gardiner, former Conservative MP for Reigate and briefly the only MP ever for the late Sir James Goldsmith’s Referendum Party. Sir George was Chairman of the influential backbench assemblage of MPs called the 92 Group, which is in many respects the arbiter of power within the Parliamentary Party. During his tenure as leader, the 92 Group pursued a Euroskeptical line which was often at odds—especially once John Major became prime minister—with that of the party hierarchy, culminating in the famous revolt against the Maastricht Treaty and Major’s description of the rebel MPs as “bastards” (hence the book’s title).

Sir George has right-of-center opinions on most issues, notably Europe, capital punishment, and the family, although his views on immigration are unsound. This, however, is true of many Conservatives, who do not understand that conservatism, if it is anything, means the conservation of a particular people in a particular place. His political opinions, his position in the 92 Group, and his physical appearance (he was once described as “Dracula left out in the rain”) have encouraged the growth of legends about him. “Were all the world a stage, [Gardiner] would be played by Vincent Price,” former MP Julian Critchley has said.

Much of Sir George’s book is consumed with minutiae about late-night conclaves in smoke-filled rooms or constituency meetings on the “rubber chicken circuit” and will therefore date quickly, but the author has included considerable detail concerning how the party machine works (or does not work). There are many interesting anecdotes, and stark insights into the vacuity of John Major. “John Major had no deep convictions and little conception of the kind of country he would like Britain to become. Leadership for him was essentially an exercise in manipulation to keep himself at the top of the greasy pole.” Sir George was a political journalist and columnist whose journalistic experience is evident in his lucid and unpretentious style. Those who have a basic knowledge of the Conservative Party and are interested in the personalities involved will find A Bastard’s Tale well worth reading.

Peter Hitchens, broadcaster and Daily Express columnist (also, ironically, the brother of Christopher Hitchens), has produced a well-written and thoughtful overview of cultural trends in his Abolition of Britain. British Tories, for the most part, still do not realize the importance of cultural politics, and their (often rather dreary) books reflect this. Hitchens’ penetrating one begins to address this deficiency.

Hitchens starts by quoting Tony Blair’s words in 1997: “I am a modern man. I am part of the rock and roll generation—the Beatles, color TV, thats the generation I come from.” For Hitchens, this somehow encapsulates the difference between the old Britain, which ran the world’s largest empire and defeated Nazi Germany, and the new “People’s Britain,” which could elect a ludicrous figure like Blair as its prime minister. Like many other conservative-minded people, he found the extraordinary scenes surrounding the funeral of Princess Diana curiously disgusting, signaling the end—or at least a nadir—of British restraint, common sense, and dislike of exhibitionism, by contrast especially with the dignified funeral given Winston Churchill in 1965. One of the most effective parts of the book is the “transplantation” of a mourner from the gates of Kensington Palace in 1997 to the Britain of 1965, where this “time traveller” is confronted not just by lovable, cheeky Cockneys and polite shop assistants, but also by poor-quality food, dowdy clothes, and “rather low” standards of hygiene. Yet there is no doubt which period Hitchens prefers. The book is divided into 15 chapters, plus an introduction and conclusion, dealing respectively with emotionalism, history, class, patriotism, Anglicanism, television, satire, marriage and illegitimacy, the English language, the family, pornography, soap operas, family planning, liberal intellectuals, and the influence of America. Each is rich in elegiac observations, such as Hitchens’ comments on historical awareness:

Thirty or forty years ago, we might all have known the stories of Alfred and the cakes, of Canute and the waves, of Caractacus and Boadicea, Hereward the Wake and Thomas a Becket. The titles of the parables—the Sower, the Prodigal Son, the Talents—would have instantly conjured up a picture in the rich colors of a stained-glass window . . . Now these things are as meaningless to millions as the forgotten myths of Greece. We drive past ancient churches, Victorian town halls, abandoned grammar schools and guano-spattered statues, quite unaware of the forces that brought them into being, the struggles they commemorate or the sort of people who built them.

The list of topics, while demonstrating Hitchens’ ambition with this book, also suggests, perhaps, an undue degree of pessimism. Like many conservative works. The Abolition of Britain may even tend to inculcate pessimism, although the author does remark that “it is not certain that the struggle is finished or that the modernizers have already won,” and that the forthcoming referendum on the single currency represents an historical opportunity to reject the “liberal conformist” worldview. He advocates a patriotic alliance with those on the left who are concerned about nationhood and the decline in morality, although the details are sketchy—and how many on the left really care about the nation-state? Yet the experiment ought to be tried.

Confirmation of Hitchens’ pessimistic conclusions might be found in a comparison of Prime Minister Blair and thrice-Prime Minister Lord Salisbury. The Beatles-and-color TV PM can only be contrasted unfavorably with the man who presided over the British Empire at the moment of its greatest extent, and whose wise stewardship ensured peace in Europe during decades of expansionist restiveness. (To be fair to Blair, most modern Tories also look bathetic when placed alongside this Victorian titan.)

Andrew Roberts, commissioned by the sixth Marquess of Salisbury to write the life of his great-grandfather, took pleasure in the task of rescuing his subject from undeserved obscurity. “I have an unpleasant suspicion,” he says, “that, aged 36, I will never again find so congenial a subject.” Roger Scruton, editor of the Salisbury Review, has said that the journal’s title pays honor to an ideal prime minister who “never did anything,” i.e., never passed any legislation. Joking aside, not only did Salisbury for the most part eschew legislative remedies, but his diplomatic labors were carried out exceedingly discreetly. Salisbury despised compliments, which he called “discreditable to the utterer and odious to the receiver,” and discouraged personality cults of the sort which grew up around Disraeli and Gladstone. As the author notes sardonically, “There could never be a People’s Robert . . . ” It is probably for these reasons that Salisbury is neglected even by thoughtful Conservatives. Yet he wrote over two million words of trenchant political commentary and book reviews, displaying a profound knowledge of such varied non-political fields as German philosophy, science, and theology. Historian Robert Blake has called him “the most formidable intellectual figure that the Conservative Party has ever produced.” How many could combine the office of prime minister with the presidency of the British Association for die Advancement of Science, or present a highly regarded critique of the theory of evolution to an audience made up of some of the greatest scientists of the time? Obviously, any man who could be described as “too Conservative for modern times . . . a man of a past age, [who] has no sympathy with life, the stir and growth of the present and no belief in the future” is worthy of study.

Roberts combines scholarship with caustic humor. He takes particular delight in remembering the verses of the jingoist Alfred Austin, including the masterful couplet from a poem attributed to him on the illness of the Prince of Wales: “Across the wires the electric message came: / He is no better, he is much the same.” Also, he enjoys quoting Salisbury’s famous red-inked bons mots and marginalia. “If Admiral Hornby is a coolheaded, fearless, sagacious man, he ought to bring an action for libel against his epistolary style,” Salisbury commented on an 1878 letter. Touches like these, as well as the realization that one is sailing in little-known waters, make reading Salisbury an unmitigated pleasure. There may never be another PM quite like him, but while there are enough people interested in Lord Salisbury for a major publisher to bring out his biography, surely all cannot be lost.

[A Bastard’s Tale, by Sir George Gardiner (London: Aurum Press) 280 pp., £18.99]

[The Abolition of Britain, by Peter Hitchens (London: Quartet Books) 351 pp., £15.00]

[Salisbury: Victorian Titan, by Andrew Roberts (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson) 938 pp., £25.00]

Leave a Reply