In the middle part of this century one of the main staples of the Anglo- American reading public was the historical novel, or romance. Such “swashbucklers” were not great literature, but they had their virtues. In the hands of skilled writers like C.S. Forester or Kenneth Roberts, they introduced a great many people to some decent history which they would not otherwise have encountered.

Of course, “historical” themes have often been employed by great writers—as in War and Peace, George Garrett’s Elizabethan novels, or, in the case of the War Between the States, such works as Andrew Lytle’s The Long Night, Caroline Gordon’s None Shall Look Back, or Gore Vidal’s Lincoln. But I am speaking of writers a cut below this level—though the dividing line between a great and a very good writer is not necessarily that sharply defined. Historical novelists like Forester and Roberts and many others flourished in a day when millions read them along with William Faulkner in the old Saturday Evening Post.

Forester’s Captain Horatio Hornblower, Roberts’ Northwest Passage, Rafael Sabatini’s Captain Blood and Scaramouche, and Kathleen Winsor’s Forever Amber, along with many others, became lavish movie productions that brought to the masses a not-contemptible elementary introduction to important epochs of the past (and managed to entertain them without gore, four-letter words, or onscreen copulation). Similar works that were excellent but which did not make it into the movies were the Civil War and World War stories of John W. Thomason and James Warner Bellah, and the colonial novels of Inglis Fletcher. Though romanticized, such works were generally accurate in historical setting. Their fictional characters were genuinely representative, if somewhat unnaturally highlighted, persons, and they mingled with real historical figures who were authentically portrayed and brought to life.

If there is any merit in this genre of literature, we have indeed fallen on evil times. The staples of the reading public, and the viewing public, are now such pseudohistorical fictions as the works of the execrable John Jakes and the faker Alex Haley. The trouble with such books and the sordid television docudramas that are made from them is that, while they claim to be historically researched, they lack any connection with or understanding of the spirit of the tunes and peoples, the social and psychological context, they are allegedly portraying. They are historical soap operas, pandering to the most superficial sentimentalities and concupiscences of our own time rather than educating us to the far and unknown country of the past.

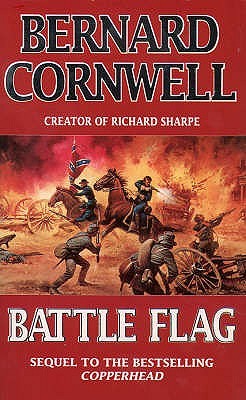

What such a decline reveals, of course, is what everybody already knows, that the powers-that-be in American cultural logistics have essentially lost (or rather never had) any connection with the fabric of American history and society, or indeed of Western civilization: they live in a multicultural world of ephemeral slogans and stimulations. The English are not quite so degenerate, in this respect at least, as measured by the fine set of historical romances about the American War Between the States that have issued in rapid succession from the pen of Bernard Cornwell. The recently published Battle Flag follows The Starbuck Chronicles, Copperhead, and Rebel, which are already in mass paperback editions. Cornwell, who before he turned to our war was already well-known for his Sharpe’s Rifles stories of the Napoleonic wars, has the virtues of those older historical romancers mentioned above.

The hero, Nate Starbuck, is the scapegrace son of a Boston Abolitionist preacher who finds himself in Richmond at the outbreak of the war and is adopted into the Southern community and army. Starbuck is a convincing character, with psychic depth, and Cornwell includes him with a panoply of other characters who, unlike Jakes’ or Haley’s, actually think, talk, and act like real 19th-century Americans. The characters sometimes verge on caricature, but they are authentic and well-drawn caricatures; that is, they are genuine representative types.

As Starbuck participates in the fate of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in Falconer’s Legion—Battle Flag concludes with Second Manassas—he encounters a host of real Southerners, and some real Northerners as well. There is the supercilious blueblood, the tough mountaineer sergeant, the country schoolmaster who develops an unexpected taste and capacity for warfare, the born-again slave trader, and many others. These characters ring true as real types from our past. And on each side there is the ambiguous mixture of good and evil, honor and vileness. For instance, of two Southern Unionists one is a sincere Abolitionist and the other a plundering opportunist. Real historical personages—in Battle Flag, John Pope and Stonewall Jackson—are integrated skillfully by Cornwell and portrayed authentically. His battle narratives arc as well done, as vivid, moving—and wrenching—as they can be.

It is important that Americans regain a real sense of our history that transcends the slogans and cartooning of the mass media. We will not get it from the vast establishment of academic historianship which has bureaucratized itself into irrelevance to the public discourse. Historians, increasingly and for the most part, speak only to each other (and even then they don’t listen). If we do begin to recover some sense of the past, it may be from writers like Cornwell. The Starbuck Chronicles is a pleasant and easy place to start your reeducation on the War Between the States.

[Battle Flag, by Bernard Cornwell (New York: HarperCollins) 384 pp., $20.00]

Leave a Reply