Like most Western children, I was reared partly on fairy tales. Presented in beautifully illustrated Ladybird books, these were as much a part of my early childhood as the house decor, encouraging me to read and arousing inchoate ideas of an ur-Europe of forlorn beauties, wandering princes, vindictive stepmothers, dangerous fruits, fabulous treasures, ravening beasts, warty witches, magnificent chateaux, and thorn-swathed castles lost in trackless forest. When I encountered the Disney versions I swiftly lost interest in them, boyishly repelled by song-and-dance numbers and twee-ness. But still the stories stayed, lodged in my image of myself and the civilization to which I felt I belonged. It was years before I realized that fairy tales were much darker and more interesting than Disney or Hans Christian Andersen had led me to believe—and years more before I heard of Giambattista Basile, the most inventive of all fairy-tale writers, to whom we owe such classic characters as Rapunzel and Cinderella. This elegantly translated, superbly annotated new translation of his Tale of Tales—which Benedetto Croce called “the most remarkable book of the Baroque period”—should therefore be of abounding interest to anyone who has any proprietorial regard for European culture.

Establishing the origins of traditionary tales is often impossible, stemming as many do from before written history and the commonalities of the human condition leading to adventitious parallels even in widely separated cultures. For example, the ninth-century Chinese folk tale of Yeh-hsien is reminiscent of Cinderella—a girl ill treated by step-relations but aided by a giant fish to attend a great ball attired in kingfisher-feather dress and gold shoes, one of which she mislays and which is too delicate to fit anyone else, until at last the lovelorn royal suitor finds her in a scullery. Tales have also interpenetrated each other to some extent through borrowings and translations. The Arabian Nights, for example, has partly Indian origins, compiled by Ashokan folklorist intellectuals in the third century b.c. as the Panchatantra, from stories that were old even then. (They were not translated into Arabic until the eighth century.) The cities of the Mediterranean littorals have always been interfaces as well as flashpoints, and one of the oldest and greatest of these was Naples, where Giambattista Basile first bawled lustily for attention circa 1575, the newest addition to a socially ambitious middle-class Posillipo clan.

The youthful Giambattista was reared in a rich-historied, Vesuvius-conscious, lushly grown, staggeringly vital city of around 200,000 souls, caught between its unquietly sleeping pagan past and the splendid Catholicism of the 16th century, Commedia dell’arte and the Counter-Reformation, Harlequin and the Holy Ghost. In summer, he probably swam, as one day I did, in the swelling bay beneath the ruins of a Roman summer house—perhaps that of ogre-like Vedius Pollio, a first-century b.c. equestrian who fed slaves to lampreys—and doubtless attended High Mass at the Cathedral of San Gennaro, where thrice yearly throngs come to see the miraculous liquefaction of the patron saint’s ichor. Etruscan, Greek, Western Empire, Byzantine, Ostrogoth, Lombard, Saracen, Norman, Hohenstaufen, Angevin, Spanish, and Near Eastern influences vied in everyone’s ether, while overlapping visionaries like Giordano Bruno, Bernardino Telesio, Caravaggio, and Saint Joseph of Cupertino augmented the sensory-intellectual banquet.

Naples’ part-Spanish nobility proving slow to patronize the young Basile, like other ambitious Campanians he decamped northward, eventually becoming a mercenary guarding Venice’s Cretan outpost of Candia (Heraklion). Here he joined a dilettantish society, Accademia degli Stravaganti (“Academy of Oddities”), and started to write letters, verses, songs, and anagrams. By 1608 he was back home, where his sister Adriana had won European fame as a singer, fêted as la sirena di Posillipo. Helped by her connections, Basile began to garner a literary reputation as well as that of a skilled administrator, becoming secretary to noble families as far afield as Mantua and later a several-times city governor within the Kingdom of Naples. Although he styled himself Il Pigro (“The Lazy One”), in what must have been his limited spare time he turned out poetry, plays, and scholarly editions of mannerist classics in Italian, while also authoring, gathering, and restyling the mass of dialect material that he would transmute into The Tale of Tales. Circa 1624 he was ennobled as Count of Torone, and continued what an obituarist called his “very peaceful tenor of life” until falling to the flu in 1632.

It is oddly predictable that Basile’s scholarly works should have fallen into obscurity, and that he is remembered today almost solely for Lo Cunto de la Cunti (also called Il Pentamerone, because it contains 50 tales told within a five-day period, and as homage to Boccaccio’s Decameron), which was not published until four years after his death. Why he did not have it published is unclear. It was not a question of a sophisticate embarrassed by his provincial roots, since he always championed Neapolitan artists and writers. It might have been difficult to find a publisher, translator Nancy N. Canepa suggests. Perhaps he did not feel it was ready for publication. In any case these stories were intended to be told rather than read—and told within a circle of listeners. The collection is subtitled “Entertainment for Little Ones,” but the intended audience was decidedly adult—aesthetes, intellectuals, and wits, who would appreciate Basile’s ornate language and lavish metaphors, his torrent of classical and contemporary allusions, sly squibs, urbanity, and lugubrious eclogues on courtly life or moral virtue. There is also surrealism—such as in The Crow, when a king becomes besotted by a freshly killed crow whose blood has leaked onto white marble and searches ever after for a wife with such coloration of hair, lips, and skin. In short, the stories are characterized by what Cambridge don E.R. Vincent called “euphuistic sophistication.”

Older children would, however, probably have been shocked-delighted by Basile’s gleeful descriptions of sex, his paragraphs of profanities, and comical conceits such as elderly and deformed storytellers beguiling the periods between narrations playing chasing games and hide-and-seek. Then there are magical transformations, gore, and grotesquerie by the cartload—to the extent that it is sometimes a relief to take refuge in Canepa’s pellucid footnotes.

The Tale of Tales went through several partial or complete Neapolitan editions between 1634 and the early 18th century, then passed into the Bolognese dialect, and at last into Italian. In 1846, it was translated into German and, in 1848, into English (by John Edward Taylor, illustrated by Cruikshank). The best-known Englishing, however, was by that bourgeoisie-scourging romancer Sir Richard Burton in 1893.

Basile was vastly original, obviously, but his urbane auditors would have recognized all kinds of antecedents. Beneath all the phantasmagorical, sometimes disgusting detail—guitar-playing crickets, the decapitated being reanimated, a wizened dyer who bleaches and pins her skin to fool a king into sex, geese being used as toilet paper, cockroach suppositories—lie deep, millennia-old structures, like palaces swallowed by forest but visible from the air. These tales are crammed with traditional tropes, some of the 2,500 enumerated so laboriously (and, one suspects, slightly joylessly) by folklorists Aarne and Thompson.

The book starts with one, “The Supplanted Bride”—the unsmiling princess Zoza forced into laughter by witnessing an argument between an old woman and a boy, ending with the enraged crone cursing Zoza for laughing. This curse inevitably involves the princess being cheated out of her prince by an ugly and foolish slave, whom he marries instead. But kindly (and apparently inegalitarian) fairies inevitably aid Zoza, and social equilibrium is restored after a salutary (but unserious) tossing and goring. These stories are more psychological safety valve than moral lesson or political message. As Iona and Peter Opie observe in The Classic Fairy Tales (1974),

In the most-loved fairy tales, it will be noticed, noble personages may be brought low by fairy enchantment or by human beastliness, but the lowly are seldom made noble. The established order is not stood on its head.

Classical and medieval literature are, as Canepa notes, full of fates being circumvented, gods being outwitted, monarchs being lampooned or traduced, heroes who can be monsters, time-slips and bizarre metamorphoses. As these ideas endlessly return, so do character types, imagery, and styles. Basile’s “unexpectedly modern” heroines are not actually more “empowered” than, say, Clytemnestra or Salome. Basile’s contemporary grossness was prefigured in Rabelais, his surrealism in Aristophanes or in works by Bosch and Arcimboldo. The author’s “stylistic hybridity” is a reflection, simply, of unrestrainable genius, rather than a model for literature (or society), then or today.

Basile was gleaning in ancient fields, but he added piquant persona to all the things he found, making them his own—but also oddly ours, aspects of an outré Europe that subsists below and still feeds into modernity. Those who wish to learn more about Naples, Italy, the 17th century, the baroque sensibility, and the wildest shores of Europe’s identity should avail themselves of this foundational, fantastical farrago.

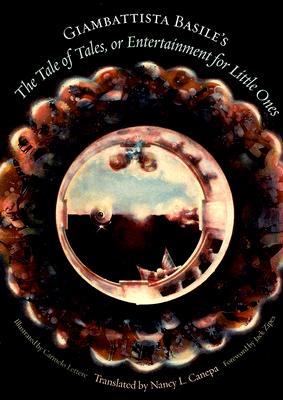

[The Tale of Tales, by Giambattista Basile, translated by Nancy L. Canepa (London: Penguin Classics) 544 pp., $20.00]

Leave a Reply