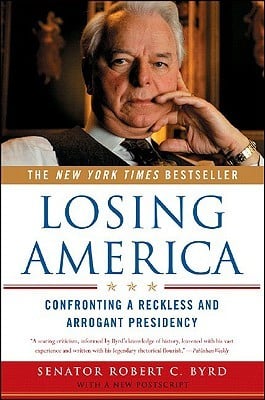

Losing America: Confronting a Reckless and Arrogant Presidency

by Sen. Robert C. Byrd

New York: W.W. Norton & Co.; 270 pp., $23.95

Robert Byrd is the ultimate political survivor. He has served in Congress for more than 50 years and has cast more votes than any other senator in American history. Publicists for the Stupid Party generally sneer at the senator from West Virginia for being an ex-member of the KKK (some 60 years ago) and for directing as much pork to his home state as possible. The occasionally sensible Michelle Malkin recently suggested that Byrd is senile. Her colleague Ann Coulter described him as a “vain, ranting windbag of a kleptocrat” shortly before Congress authorized war in Iraq. The far wiser Paul Craig Roberts recently suggested that Byrd is the “Constitution’s greatest—and perhaps only—defender in the US government.” Roberts is on to something: Byrd is the closest thing to a constitutionalist in the U.S. Senate. He is particularly concerned with maintaining the separation of powers and defending the prerogatives of the Congress.

Subjects that provoke Byrd’s anger in Losing America are President George W. Bush’s attempts to infringe on Congress’s spending power and the latter’s frequent refusal to fight back. Immediately after the attacks of September 11, the President sought “such sums as may be necessary” to respond to the terrorists, and Congress did not require the executive branch to account for how the money was spent. The infamous $87 billion request in the fall of 2003 contained several provisions undermining congressional appropriations power, including three billion dollars in “transfer authority” funds for Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld to spend as he sees fit. Byrd states that, “in setting up large accounts to be spent without congressional ‘meddling’ we have legislated a return to the slush fund.” In attempts to score points against the Kerry-Edwards ticket (both men voted nay), administration supporters regularly imply that voting against the appropriation was the equivalent of voting against the troops—as if American soldiers would have been abandoned in the field had Congress failed to fund the “War on Terror.” Byrd shows that the issue is far more complex.

The middle of President Bush’s term was marked by a stunning victory for the Republicans in the 2002 elections, built largely on the GOP advantage on national-security issues and on Republican support for creating a Department of Homeland Security. The (bad) idea for this new department originated with Sen. Joseph Lieberman (D-CT). President Bush originally made Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Ridge a member of the White House staff with responsibility for homeland security, answerable only to the President. Citing his position as a presidential advisor, the White House turned down requests from Byrd (then chairman of the Appropriations Committee) and Sen. Ted Stevens, a Republican from Alaska, to let Ridge testify about a homeland-security funding request that would cover multiple agencies. Before the administration flip-flopped on creating a Department of Homeland Security, the two senators introduced legislation to require that Ridge be confirmed by the Senate, so that he would have to testify.

Byrd denounces the President’s rush to create the department without thinking the issue through. He describes a particularly fruitless meeting on this topic in which members of Congress were brought in to serve as “potted plant” backdrops. Byrd’s assessment of the President is scathing:

I was struck by the president’s dismal performance. To say it was mediocre would be a gross exaggeration. He was disorganized, unprepared, and rambling. This fellow was all hat and no cattle, as they would say in Texas. It was obvious that he had no idea what was in his Department of Homeland Security proposal, nor did he seem to care.

While so many prominent Democrats, spines as stiff as macaroni noodles, went along with the administration’s drive to invade Iraq, Byrd stood firmly and solidly against the rush to war. In Losing America, he examines the war from several different angles. As an advocate of the separation of powers, he is especially angry about the blank check that Congress gave the Bush administration to wage war. Byrd describes a depressing meeting of Democratic senators before the vote, in which he learned that some of his colleagues helped draft the resolution that “complete[ly] hand[ed] over [the] congressional war power to the president.” Most of them then voted for the resolution in order to be able to highlight other issues in the 2002 elections.

Senator Byrd also takes offense at Bush’s carrier-landing stunt in May 2003, during the brief triumphal period after Saddam’s fall and before terrorists and guerrilla warriors started to exact a heavy price in blood from U.S. troops and Iraqi civilians. Byrd strenuously denounced the President from the floor of the Senate a few days later. He includes the speech in the book and notes the contrast between the “simple dignity” of Abraham Lincoln, speaking at Gettysburg, and the “flamboyant showmanship” of the current occupant of the White House.

There is plenty of politics in Losing America, which nevertheless rises above the usual partisan blather. Byrd’s criticism of the President is harsh but principled, and he does not spare his Democratic colleagues. The book is a worthy addition to what will someday be a vast library of volumes describing the disaster that is Bush II’s presidency.

Leave a Reply