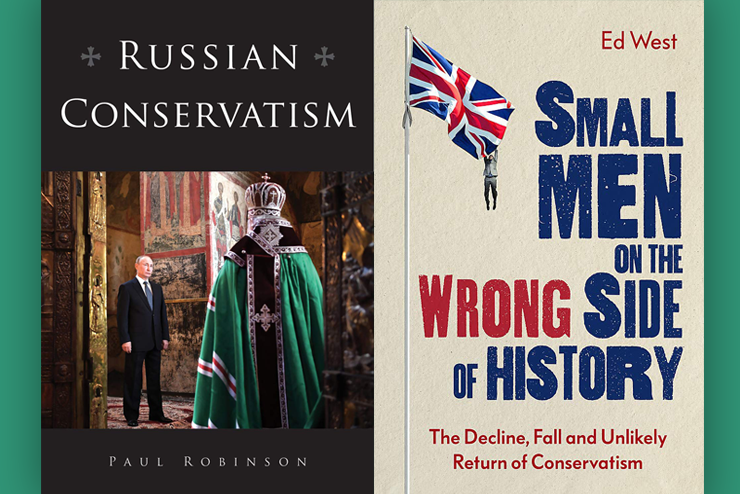

Russian Conservatism, by Paul Robinson (Northern Illinois University Press; 300 pp., $39.95). Canadian historian Paul Robinson has written a highly accessible study of Russian conservatism that extends from the early 19th century down to the present time.

According to Robinson, defenses of the Russian homeland as a spiritual entity and the accompanying rejection of Western late modernity did not start the day before yesterday. These positions are deeply rooted in Russian reactions to Westernization. In fact, much of what has fueled Russian traditionalism derives from this confrontation with a Western world that shows certain cultural and religious links to Russia, but which is also perceived as being different. It is the traditional Russian right that has emphasized this difference in order to preserve what it considers to be the unique character of its country.

One feature of Russian conservatism, which Robinson illustrates by showing all the strains of this movement, is its remarkable variety. Robinson begins his analysis by focusing on beliefs shared by all Russian conservatives. These unifying elements would include some degree of ethnic nationalism, devotion to the Orthodox Church as an uncorrupted form of Christianity, and resistance to the West as a source of dangerous liberal ideas. Robinson examines how these foundational principles have shaped every instantiation of Russian conservatism, from the rule of Tsar Alexander I (1801-1825) to the presidency of Vladimir Putin.

The operation of these principles and attitudes among Russian traditionalists, however, should not cause us to believe that all forms of Russian conservatism are the same. Russian conservatives have differed on a wide range of policy issues, particularly on the question of compromise with Western liberal influences. Robinson takes on Russian historian Richard Pipes who argued that the Orthodox Church in Russia has been mostly a tool of the Russian state. Moreover, according to Pipes, Russian conservatism has been a defense of autocracy. Robinson presents a much more nuanced picture of both the Orthodox faith in the lives of Russians and of the divergent positions found on the Russian right.

Two points may be worth making in assessing Robinson’s excellent monograph. First, there is nothing sui generis about the critical response of Russian conservatives in the 19th century to the economic, political, and cultural modernization that they associated with the West. The same attitudes characterized French, German, British, and other Western conservatives in the 19th century. But unlike in Russia, the conservative reaction in Western countries yielded to other movements that have advanced modernity. Today’s British Conservative Party and Macron’s En Marche! bear little to no resemblance to the English or French right in the 19th century. Western “conservative” or “Christian” parties are now marketing a name brand they find profitable to hold on to, just as Yuengling Beer in Pennsylvania advertises that it has the oldest brewery in America.

In Russia, an essentially 19th-century nationalist right survives under Putin’s rule. This may be at least partly attributable to the Ice Age effect of Soviet rule, which, curiously enough, slowed down modernization in the name of a revolutionary ideology. One of our contributors in the March number argued that Soviet Communism built a barrier throughout Eastern Europe and Russia against feminism, gay rights, and multiculturalism (“How Communism Saved the Eastern Bloc From Cultural Marxism,” by Ian Henderson). These are all forces that have triumphed dramatically in the U.S., the Anglosphere, and most of Western Europe.

By contrast, in Russia an older cultural and political tradition survived Communist rule and has re-emerged in the post-Communist era. Robinson shows how the Soviet regime cultivated conservative nationalism as a pillar of its system of control. Some self-described Russian conservatives believed the Soviet state was preserving the Russian nation by creating a powerful Russian imperial state. This may have been true, if one overlooked the brutal fashion in which the Soviet state ruled and its war against religion, including the Russian Orthodox Church.

The second point is that there is no reason to measure the degree of conservatism in Russia by how affirmatively it accepts a market economy for its citizens. Russia’s tradition is not a classical liberal one; nor is its government’s involvement in the economy designed to advance LGBTQ rights or the liberation of women from the family. Russian collectivism has a right-wing, not a left-wing, character, and supposedly aims at the protection of core social institutions.

That does not mean that state bureaucracies in Russia have not been corrupt. They most certainly have been. What it does mean is that the state is conceived of by Russians in a conservative way. In the U.S., and elsewhere in the Western world, the advance of a centralized administrative state has been accompanied by massive social engineering, and almost every program now undertaken by “liberal democracies” is supposed to be benefiting groups allied to the sociocultural left. From Robinson’s book it would seem this has not been the case in Russia.

(Paul Gottfried)

Small Men on the Wrong Side of History: The Decline, Fall and Unlikely Return of Conservatism, by Ed West (Constable/Little, Brown; 432 pp., $17.99). Yeats’ memorable phrase “the best lack all conviction” came to mind as I read British journalist Ed West’s latest book, which is part review of conservative history and philosophy, part survey of the research on political belief, and part memoir of West’s development as a conservative in the land of the left.

A child of London newspaper journalists and a writer himself at The Catholic Herald, The Daily Telegraph, and The Spectator, West writes of having been tormented his entire life by his natural conservative political disposition, which he concealed out of shame, “hiding my horns and tail and mimicking a humanoid appearance so they don’t know I’m not one of them.”

Conservatism’s long-term problem, in West’s view, is that it is low-status and unattractive to the ambitious, with conservatives having been shown the door at all of society’s premier institutions. Suffering from an “extremely low embarrassment threshold,” West nearly panicked when he was spotted by an acquaintance while canvassing for a Tory candidate. After writing frankly about Britain’s immigration problem in his 2013 book, The Diversity Illusion, he was courted over the phone by Steve Bannon to join Breitbart News, which he turned down, as “it would mean being hated and shunned, while being praised and supported by some absolutely terrible people.” After joining a Brexit think tank in 2016 to write speeches advocating for Britain’s departure from the EU, West nursed secret doubts on the wisdom of separation, and was dismayed when the news came in that the Leavers had unexpectedly won. “What had we done?” he lamented.

This can grow tiresome quickly, despite the charm of West’s skillful prose. It’s too bad, because despite his tremulous attitude, West provides many insights into the current conservative political predicament, as well as an interesting survey of research into the genetic, biological, and social factors that make individuals and groups hold one set of political beliefs or another.

One such insight is that membership in political groups tends to be formed by opposition—shared enemies, rather than shared beliefs, tend to push people into one party or another. Based on this, West predicts that the current trend in America of Democrats identifying as the diversity party while pushing anti-white rhetoric will tend to drive conservatives, however reluctantly, into an opposing racial stance. “I imagine the main thing holding the broad Republican coalition together will be whiteness,” he writes. “And inevitably something similarly depressing will follow in England.”

The current hostility toward conservative thinkers “has selected the sort of person who can handle hostility, or even revels in it,” West writes, admitting that he is clearly not one of them. If conservatism is to be anything other than “progressivism driving the speed limit,” Michael Malice’s phrase, it needs people with more passionate intensity than West has to offer.

(Edward Welsch)

Leave a Reply