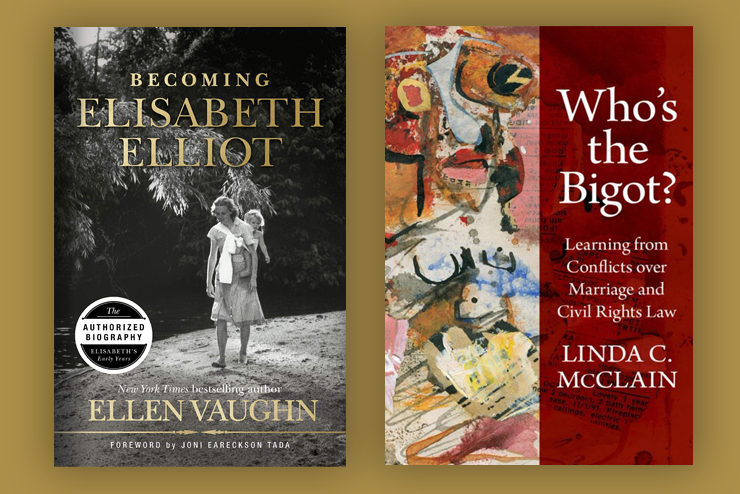

Becoming Elisabeth Elliot, by Ellen Vaughn (B&H Books; 320 pp., $24.99).

This is the official biography of the wife of famed missionary martyr Jim Elliot, who was killed along with four other missionaries while attempting to bring the Gospel to a group of savage natives in the South American jungle during the mid-1950s. Elliot was launched onto the international scene not only because of her book on the lives of the five murdered men, but also by Life magazine’s coverage of her expedition back into the jungle to live and work with her husband’s killers.

Elliot’s intense suffering extended beyond the brutal death of her husband Jim. The book maps her long, uncertain, and often agonizing courtship with him, and the difficulties of their work as missionaries and translators.

Like the biblical Job, Elliot wrestled with hard questions—ones that many good Christians sometimes shy away from asking. She clung to Scripture and her relationship with God, emerging from trials with poignant and profound insights. “Suffering is never for nothing,” Elliot was fond of saying throughout her life.

This grief, this sorrow, this total loss that empties my hands and breaks my heart, I may, if I will, accept, and by accepting it, I find in my hands something to offer. And so I give it back to Him, who in mysterious exchange gives Himself to me.

A well-educated woman, Elliot was not afraid to consider the intricacies of suffering displayed in secular works; she even found and recorded choice insights from D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, a book once considered pornography, to help her process her grief. Regarding these unorthodox tendencies in Elliot’s thought, Vaughn opines that Elliot has more in common with today’s millennial generation than she did with her own. Like Elliot, millennials “are not looking for a seal of approval from some authority figure,” instead they “evaluate material on its merits, regardless of where it comes from, and then make their choice.”

Elliot’s story has strong merits, not only in its raw honesty and its message of hope and healing, but also for pointing its readers toward the Divine Source.

(Annie Holmquist)

Who’s the Bigot?: Learning from Conflicts over Marriage and Civil Rights Law, by Linda C. McClain (Oxford University Press; 304 pp., $39.95).

The United States Supreme Court has declared that the Constitution prohibits laws against integrated schools, miscegenation, sodomy, same-sex marriage, and affirmative action for homosexuals. These progressive pronouncements have provoked no effective pushback from either originalists or champions of democracy.

But why? In this examination of the recent history of civil rights and family law, Boston University law professor Linda McClain reveals the formula for progressive success: accuse opponents of bigotry and make them social pariahs. The lesson is that conservatives need to demand reform before things get worse.

While the progressive strategy has been effective, McClain believes that hurling insults like “bigot” at religious traditionalists is losing effectiveness; traditionalists have adopted the same strategy, screaming “bigot” right back. Instead, she recommends encouraging the “unwoke” to overcome their implicit biases and to educate themselves about the harm they do to others when they insist on living by their principles. Her goal is to reach a “settled social consensus” that makes sincerely held religious beliefs inert.

But what is bigotry, according to McClain? She begins with an examination of family reactions to interfaith and interracial marriages, quoting a definition of a bigot as someone “unreasonably wedded to a particular religious creed, opinion, or ritual.” But she concedes social science shows increased divorce rates for those unions and that societies have a legitimate interest in perpetuating themselves; she cites a rabbi saying that no prophet ever proposed racial or religious groups should cease existing in the interests of universal brotherhood.

McClain observes approvingly that the span from Brown v. Board of Education to Obergefell v. Hodges chronicled the death of originalism, replacing it with “‘abstract aspirational principles’ that we seek to realize over time.” Constitutionality became a moving target, requiring a “moral reading.” Conscience is moral disapproval; moral disapproval is bigotry; and bigotry is unconstitutional.

Conservatives should not forget that for more than half a century the state has been forcing religious people—the first being segregationists—to violate the tenets of their faith, not only those who object to same-sex marriage. Conservatism’s attempt to distinguish these two sets of believers on principle has been incoherent. Transgenders will be the next group to trample religious traditionalists under the Constitution of Settled Social Consensus, with polygamists to follow. After all, love is love.

(Betsy Clarke)

Leave a Reply