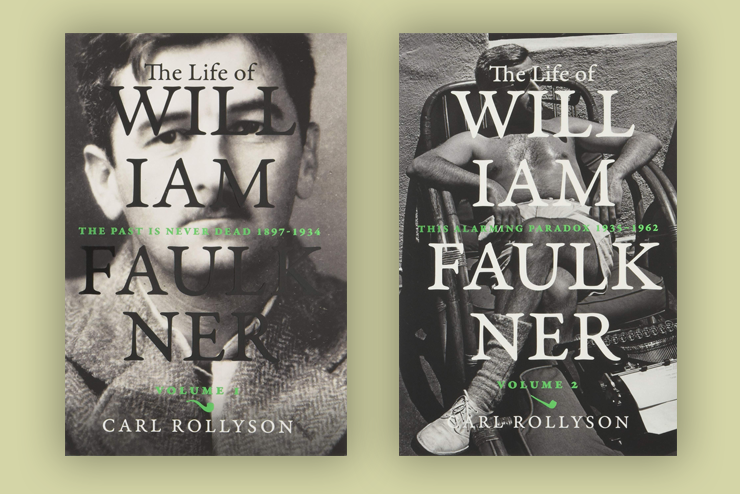

The Life of William Faulkner. Volume 1: The Past Is Never Dead, 1897–1934

512 pp., $34.95

The Life of William Faulkner. Volume 2: This Alarming Paradox, 1935–1962

656 pp., $34.95

by Carl Rollyson

University of Virginia Press

Readers might be excused for exclaiming, “What! Another Faulkner biography?” Yet one can make a case for a fresh examination of this Nobel laureate.

“The Past Is Never Dead” is the subtitle of the first volume of Carl Rollyson’s new biography, quoted from his subject, and it furnishes a useful motif. In William Faulkner’s work, the importance of history and the past as present cannot be exaggerated. He was, as literature professor Hans Skei put it, “steeped in history” of the Old South and its 20th-century legacies. In explaining the choice of Faulkner for a Nobel Prize, Swedish novelist Gustaf Hellström mentioned “the bitter fruits of defeat” explored in his fiction.

Rollyson is a versatile and experienced biographer and professor emeritus of journalism at the Bernard Baruch College at the City University of New York. In re-examining Faulkner’s life, he has done extensive research, especially in the Carvel Collins Collection at the University of Texas, which holds 114 boxes of Faulkner’s documents and correspondence. He reintroduces and adds facts, evaluations, and frank speculation, which, to his credit, he acknowledges as his own. He provides critics’ responses to Faulkner’s writing, and he carefully examines the author’s screenplays in light of his fiction and personal experiences.

There is value in Rollyson’s enterprise because of the shortcomings of earlier biographies. Joseph Blotner’s two-volume study Faulkner: A Biography (1974), authorized by the subject’s widow, Estelle, was not without its critics. Blotner dealt gingerly with Faulkner’s heavy drinking and love affairs and concealed other information. Although Estelle had died by the time Blotner’s work was published, other family members, including his daughter, were still alive. Blotner, even if he had been aware of it, surely would not have included the sexual language that Rollyson reproduces. Blotner’s subsequent updates corrected and enlarged upon various matters but did not offer entirely new appraisals.

Publication of Rollyson’s study by the University of Virginia Press is fitting. It was on that campus where Faulkner first gained academic recognition and on which he served, in 1957, as writer-in-residence, an early specimen of that breed, subsequently holding a prestigious lectureship. The library owns a large collection of Faulkneriana, and Blotner was a faculty member there.

Biographers are not required to provide what is called an “overarching meaning.” Their subject’s life itself furnishes the thrust and themes. But, in providing comprehension and pleasure, a literary biography should present a career. The successful biographer establishes a personal context and traces the origin, development, execution, and reception of creative works. He places his subject likewise in a larger perspective of pertinent literary history and adds the appraisals of others.

The sound principles of such an undertaking include rejecting, firstly, the call by mid-20th-century New Critics to separate works from their authors’ lives and intentions, and, secondly, Michel Foucault’s absurd claim denying “the sovereignty of the subject treated as an autonomous agent” (that is, there is no “author”). Equally questionable are simplistic Freudian readings, which detract from many modern literary biographies. Nor can the self be treated as the “mirage” that Jacques Lacan identified, nor as an “oppressive authority,” a creation of power structures. Neither should the literary biographer accept the New Historians’ claim that the historical context of cultural products is irretrievable. True literary biography is directly opposed to these theories. It both assumes and undertakes to reveal the integrity of the writing project.

Rejecting these 20th-century notions separating texts from contexts is especially important in a biography of a man like Faulkner, who is someone of a particular place: the South. The late New Orleans novelist Shirley Ann Grau observed, in connection with her Pulitzer-winning novel The Keepers of the House (1965), that “no person in the rural South is really an individual. He or she is a composite of himself and his past. The Southerner has been bred with so many memories that it’s almost as if memory outreaches life.”

above: William Faulkner (Everett Collection Historical/Alamy Stock Photo)

Persistence of the past in Faulkner’s vision, and its weight on the individual, do not mean, however, erosion of the person. On the contrary, as the artist’s project transcends his surroundings, powerful characters of his creation likewise transcend, by their individuality and intense humanity, the givens of their place and time.

For the most part, Rollyson has endeavored to fulfill the biographer’s charge, avoiding the pitfalls of modern criticism. He resists the unconscious as an easy explanation, while noting Faulkner’s “Freudian orientation” and emphasizing sexuality in the current fashion. Faulkner’s writings receive lengthy treatment, perhaps beyond what a biography calls for (there is a 36-page section, plus more pages elsewhere, on Absalom, Absalom!). Whether seasoned readers will be glad to refresh their memory, thus avoiding undertaking a reread of the source material, is uncertain. While previous critical approaches and opinions (including reviewers’) are cited, the summaries and assessments of Faulkner’s work are the biographer’s own.

Who is the Faulkner emerging from Rollyson’s study? As the subtitle of the second volume, “This Alarming Paradox,” suggests (again, a Faulknerian phrase), he was a complex and contradictory person. (Aren’t many artists a knot of contradictions? Yet trajectories and patterns remain discernible.) Rollyson contends that, like blacks and homosexuals, Faulkner felt “left out”—hence his ability to convey “black rebukes to white power.” Unimposing in stature, with early interests in poetry and drawing, he initially appeared a lightweight in the macho world of southern manhood—hence, perhaps, his eagerness to serve during World War I.

When the U.S. Army rejected him, Faulkner joined the Royal Canadian Air Force. Later he embroidered his war record considerably. His athletic abilities, expressed in tennis, horsemanship, and his fishing, boating, and hunting skills were genuine, however. He remained boyish (an attractive attribute, usually); or was it childish (and therefore less attractive)? The enduring appeal that military uniforms held for him seems to have been a sign of immaturity; his attachment to family much less so.

Convinced—rightly—of his genius, Faulkner remained faithful to his literary vocation and its imperatives, while leading a complicated life, in a marriage sometimes unhappy. Along with heavy family responsibilities, he had extensive properties, starting with an old house, originally in poor condition, which he named Rowan Oak. Rather improvident and usually in arrears, though erratically practicing thrift, he made sacrifices to keep and enlarge his holdings, begging for payment extensions and publishers’ advances. Both ambitious and enterprising, he was nonetheless diffident—keeping at the edge of a party, for instance—modest, and not smugly self-important. That he outgrew the rather oppressive agency of Oxford, Mississippi, attorney Phil Stone, an invaluable, if heavy-handed, early booster, is not surprising.

above: exterior of the Rowan Oak house, Faulkner’s home in Oxford, Mississippi, from 1930-1962 (Wikimedia Commons/Wescbell)

Faulkner’s experiences elsewhere became extensions of himself. Memphis was important, for practical reasons and human interest. Months in New Orleans were crucial. In Europe he appreciated the vast cultural resources; in New York City, he made friends, visited publishers and bookstores, enjoyed the company at the Algonquin Round Table, and, of course, drank. The many months spent in Hollywood working on film scripts were far from worthless, both to him and to the industry. Rollyson remarks that, while biographers have treated Faulkner’s Hollywood stays as a digression, “they were all of a piece with the rest of his life.” Yet he always needed to return to his home soil and its people, mores, and speech.

A salient claim in Rollyson’s biography is that, along with “a new kind of novel,” Faulkner produced “a new kind of history,” in which “history itself is the intense focus of his attention.” This claim is not defined precisely nor illuminated by reference to historians or a school of historiography. Readers are left on their own. Is it history seen through Faulknerian “critical consciousness,” leading to a rewriting of the past? Or simply a new “sense of history,” involving reassessing Southern convictions on race and the Civil War—as in his film script for Battle Cry—and denouncing segregation?

Denounce it he did, finally, reluctantly, and in a highly nuanced manner that did not disavow the South, and chiefly on pragmatic grounds. He rejected all militant tactics. In a statement from an interview, which he subsequently both disavowed and confirmed, he remarked, “If it came to fighting, I’d fight for Mississippi against the United States.”

Although Rollyson does not specify so, the claim about a new kind of history might, plausibly, be related to Faulkner’s modernist compositional techniques. These often layered on one another, involving fragmented, disorderly, contradictory expression, suggesting “the cumulative and incremental efforts of the character-narrator historians over several generations.” For Faulkner, form and content were always very close. The style would be—or would at least suggest—the substance, as in so much modernist writing.

History is not simply exterior, linear, and objective, because the past is not. Rollyson emphasizes how Faulkner underlines its inescapability. The insight is not new, of course (think merely of Greek drama); but it is powerfully expressed in Absalom, Absalom! by the character Quentin Compson, who, Rollyson asserts, “carr[ies] with him what becomes, by the end of the novel, the burden of southern history itself.” That novel exemplifies Faulkner’s plight “as a modern man and a vestige of an earlier epoch.” Implied is the inevitability of change. Rollyson does not say that this change is dialectical, however. Hegel does not appear in the index, nor does Marx…

above: book cover for William Faulkner’s 1936 novel Absalom, Absalom! (Vintage International)

Applying a contemporary grid to Faulkner’s work, Rollyson calls on the clichéd triad of oppression by race, class (or caste), and sex to cast historical shame on the South, past and present, which, by implication, needs a second Reconstruction.

All three social identifications were already prominent in Faulknerian commentary, though not necessarily in the reified -ism form. When Faulkner wrote, class and sex distinctions were, in Mississippi as elsewhere, pragmatically recognized, and peculiar Southern aspects might be noted. Rollyson’s notion of “gender” roles then is unduly neat and ironclad. He emphasizes an instance of these roles’ threatening reversal in The Wild Palms, as if women had never before exercised initiative.

As for race, while the Old South, with its prominent paternalism and, in the 20th century, Jim Crow, was distinctive, consciousness of differences between whites, blacks, Indians, and immigrant groups, and its companion, language-consciousness, marked nearly all of America. In effect, the entire nation was, according to today’s progressive rhetoric, classist, sexist, and racist. Except, perhaps, for the far-seeing Faulkner. Possibly without realizing it, on the way to a new critical consciousness he turned racism into a “cynosure,” even an ontological category, something like the Fall, which touches all men. Or so Rollyson paints the picture, at any rate.

To those oppressive behaviors, reflecting anxiety about “the Other,” Rollyson adds fascism and colonialism. Light in August is connected to Faulkner’s “understanding of American fascism” and his own “latent fascist mentality”; the state of Alabama in his time was “fascist.”

This charge is misplaced. While its philosophical origins antedate the 1920s, and Mussolini made the term fascism available for Faulkner’s generation, Rollyson’s use of the word “fascism” does not fit, unless he means by it simply oppression. Faulkner does not exploit fascism in his fiction. A loose resemblance between anti-Semitism and Southern racism, established in one of Faulkner’s unpublished letters, underlines prejudice in each case but not political or ideological equivalence. What Rollyson gains by using the term is unclear; perhaps it is to show how far from his Confederate roots Faulkner traveled. He had seen coming, Rollyson’s argument goes, “the fascism that would engulf the world, and that his own fiction, a new kind of history, had done to expose.” Thus, a series of film scripts Faulkner wrote in the 1940s were “aimed to unite the American people in a war meant to overcome class and racial differences.”

Colonialism applies, in Rollyson’s understanding, not just to the plantation world, nor its feudal beginnings, nor its later capitalization, but to the whole of America, which from the earliest settlements on was founded on dispossession and exploitation of the earlier inhabitants. He fails to acknowledge the place of invasions and occupations elsewhere in history. Rollyson cites film scripts by Faulkner containing allusions to warfare with Indians, seizure of land, and early class structure, and speaks of what Faulkner called in another connection “recognition of one race and repudiation of another in the service of imperial nation building on land originally occupied by other nations.” To the uncertain degree that these scripts can be taken as critical cinema, they would prefigure such revisionist films as Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves.

Notwithstanding Rollyson’s emphasis on Faulkner’s “new history” and his social awareness, it can be argued that, despite inventing or adapting modernist narrative techniques, Faulkner was basically conservative. He resisted change. His vision was classical; he honored the soil and his people, illustrating in The Hamlet what Rollyson identifies as “the classic perspective of the pastoral poet.” The local embodies what the novelist called “old universal truths,” including the givens of nature and human nature and the invaluable human patrimony. Regionalism does not signify parochialism.

Dashiell Hammett criticized Faulkner’s refusal to sign any liberal or communist petitions or take an interest in reform movements. Individualistic and anti-federalist, Faulkner opposed the New Deal, preferring personal initiative. A Kenyon Review writer called him “a traditional moralist, in the best sense,” arguing that his novels were built around the conflict between traditionalism and the anti-traditional model.

above: William Faulkner receives the Nobel Prize for Literature from King Gustav of Sweden, 1949. The Nobel committee commended “his powerful and artistically unique contribution to the modern American novel.” (MARKA/Alamy Stock Photo)

A human tabula rasa seemed, to Faulkner, to be both undesirable and impossible. The flourishing of humanity was not to be engineered by force. There would always be error, failure, and sorrow. What these failings meant and how they could be accepted was the question. In The Wild Palms, a man says, “Between grief and nothing I will take grief.” (Recall Shakespeare’s Richard II: “You may my glories and my state depose, / But not my griefs; still am I king of those.”) Literature, Faulkner asserted in his Nobel speech, was to lift up man’s heart, “by reminding him of the courage and honor and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past.” Perhaps, Faulkner hoped, man can, by increments, endure and, in his term, even prevail.

Recontextualizing past literary products is inevitable, as tastes and conditions change. The German literary scholar Hans Robert Jauss viewed the process as crucial to continued understanding, along with two other critical dimensions: knowledge of the author (and his intentions) and of the original context of a work’s production. Such recontextualizing may illumine works anew. But, used abusively, it sheds light merely on the present.

The twisted application of alien or anachronistic critical viewpoints to canonic authors is widespread. Rollyson’s charges of fascism and colonialism are of the same shoddy character as facile Freudian interpretations of Shakespeare, feminist screeds against male authors (sometimes female), and Marxist categories imposed indiscriminately. Being widespread does not make such readings true; better to read through the lens by which the author saw the world—the sensibilities of his time—rather than through presentism. In any case, masterpieces endure, the current campaign against the word “master” notwithstanding.

Leave a Reply