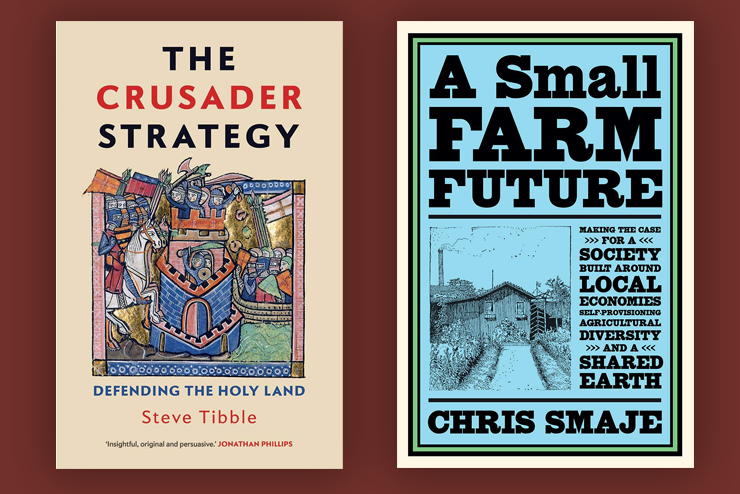

The Crusader Strategy: Defending the Holy Land, by Steve Tibble (Yale University Press; 376 pp., $35.00). If one gets his Crusades history from Karen Armstrong or the History Channel, one is likely to think that nasty and brutish Franks went off half-cocked to the Holy Land to rape, pillage, and enslave peaceful Muslims. This is an ignorant and irritating trope, and a pernicious falsehood that folks like former President Barack Obama still trot out in speeches. Steve Tibble corrects the record by scrutinizing the careful military strategies employed over the course of two centuries by the crusader states of Edessa, Antioch, Tripoli, and Jerusalem.

Tibble is the most interesting military historian of the Crusades writing today, and his most recent work is a follow-up to his 2018 book, The Crusader Armies: 1099-1187. While he does not break new ground, he helps readers see the old ground more profitably. He is an entertaining writer and his tone is often casual, but that does not come at the expense of scholarship or insightful use of historical sources.

This book fills the gap between Christopher Tyerman’s How to Plan a Crusade (2015) and Malcolm Barber’s The Crusader States (2012). Tyerman’s book is the gold standard on crusade planning and logistics. Barber’s is the best single volume on the history of the cultural, legal, political, and economic systems of the Latin East. Tibble builds on both by demonstrating how the crusader states employed coherent and sustained strategies to preserve a narrow strip of land surrounded by enemies.

As in his first book, Tibble limits his focus to the period of 1099 to 1187. Survival required multiple strategies after the crusaders successfully conquered Jerusalem. It often amounted to choosing the best of bad options. Nevertheless, these were detailed and highly developed plans carried out over decades and diverse regions by Christian rulers with varying abilities. Tibble divides long-term crusader planning into strategic categories: coastal, hinterland, Ascalon, Egyptian, and frontier.

The coastal strategy was the most successful, benefitting from army-navy joint operations and the use of naval engineers to build siege equipment. The Ascalon strategy finally brought the pesky Fatimid city into Frankish hands in 1153, but it was only temporarily successful in helping the Franks reallocate resources to aid Antioch and Tripoli to the north. The Egyptian, frontier, and hinterland strategies saw limited tactical successes but ultimately were doomed by a lack of military manpower and rural settlement. After reading Tibble’s account, one is more surprised that the crusader states succeeded at all than by their eventual failure.

(Timothy D. Lusch)

A Small Farm Future, by Chris Smaje (Chelsea Green Publishing; 320 pp., $22.50). Chris Smaje is probably the only sociologist-turned-farmer in England. This unusually ecologically-aware agriculturist hopes the sobering effects of COVID-19 will help reset society by restructuring rural areas.

Food chains are fragile due to population pressure and economic and ecological challenges, and Smaje says there should be a new emphasis on small farms and on local self-reliance over factory farming and mass-market consumerism.

These are old ideas, but in our Anthropocene age they feel increasingly urgent. Smaje makes his case carefully, patiently sifting realities from fallacies on everything from organic farming to veganism, and property rights to the supposed vibrancy of cities. He discounts the “zombie liberalism” of both left and right, and the complacent fantasy that innovation will somehow save us from the consequences of our carelessness. He combines academic insight with hands-on agronomy to argue not only that small farms can feed the world, but that they may one day be the only thing that can. Even now, Smaje asserts that such farms and organic practices can out-yield conventional agriculture, without causing comparable devastation.

Smaje is gainsaying not just agribusiness, but the whole structure of the modern state and centuries of cultural drift encrusted with snobbery against country life, manual work, and the “backwardness” of tradition. He plows a lonely furrow, pointing towards far-distant prospects to transition from consumerist and urban-oriented economies to a “distributed, omnivorous, de-centralised agricultural order.”

A minority will find Smaje’s vision attractive, because even now rural life is associated with authenticity, community, “escape,” and Cincinnatus-like moral virtue. But is it feasible as a mass movement?

Nobody wants to return to Smaje’s “hardscrabble life of toil retained in folk memory.” Few will forage for food, slaughter their own livestock, or make their own wine when the supermarket beckons. His priority is therefore to make his “materially adequate” future seem slightly more appetizing, not just to eco-conscious individuals, but more importantly to the economists, philosophers, and politicians in thrall to economies-of-scale, “growth,” homogenization, scientism, and short-termism.

There are precedents for Smaje’s vision, and hints of change. Small farms were the default setting for much of history, and many countries still have many small farms. Even the modern West is not that far removed from this tradition, and more of us are altering our attitudes, growing different crops, eating better meat, and using fewer chemicals. If Smaje is right, these choices may soon become necessities, and the “easy option” will be no option at all—and then we’ll be grateful for cultivators of his kind.

(Derek Turner)

Leave a Reply