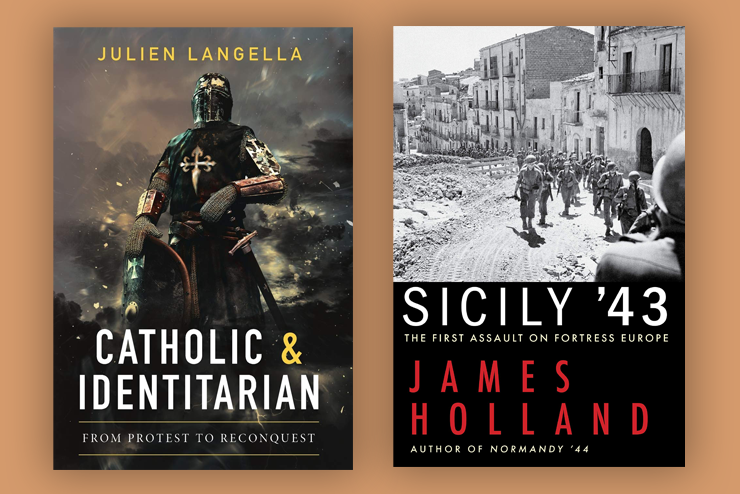

Catholic & Identitarian, by Julien Langella (Arktos Media; 338 pp., $38.95). French commando Dominique Venner committed suicide inside Notre-Dame Cathedral in 2013 as an act of protest against unrestricted Islamic immigration. One cannot but censure Venner’s sacrilegious act. Yet, calling attention to the existential threat to the West in general and France in particular is a legitimate aim. In a disorienting age that has confused the touchstones of family, faith, nationality, vocation, and even sex, the question of identity is undeniably paramount.

Given the Catholic ecclesial bureaucracy’s flamboyant embrace of globalist ideology, it is quite radical enough to point out that, as French activist Julien Langella puts it in this book, “the teachings and traditions of the Church have always respected ethnic and national borders and protected the integrity of authentic human roots.” For the benefit of those unaware of the Catholic tradition’s relationship to patriotism, Langella shows how the local, particular loyalties frequently denounced in modern homilies as “racism” have been affirmed not only by popes and Church Doctors, but by Biblical figures such as the Maccabees, Saint Paul, and Christ Himself.

Pope Pius XII declared in his Summi Pontificatus (1939) that the Church cannot “attack or underestimate” the cultural characteristics that each people “retains and considers as a precious heritage.” The recently canonized John Paul II also observed in his provocatively entitled Memory and Identity that Church teaching “speaks of ‘natural societies,’ indicating that both the family and the nation have a particular bond with human nature.”

Bound up in such seemingly innocuous statements is a critical truth from which today’s Catholic conservative establishmentarian consistently shrinks: There is no argument for denying significance to ethnicity or nationality that does not ultimately translate into an attack upon the natural family itself. Either organic and historic bonds matter, or they don’t.

“Caring for strangers has its limits,” Langella writes. “Only our Father can simultaneously love every creature on the earth with the same intensity.”

Yet, for men of weak character, a shallow love for the other expressed as hypermobile liberal internationalism proves seductive. It is far easier to gaily tour the world while prattling solicitously about the latest PC cause célèbre than it is to maintain messy yet meaningful long-term relationships with kinfolk, countrymen, and next-door neighbors. Whatever good is still to be accomplished in the 21st century will come through those willing to take the hard road, which points homeward.

(Jerry Salyer)

Sicily ’43: The First Assault on Fortress Europe, by James Holland (Atlantic Monthly Press; 599 pp., $30.00). By 1943, Hitler, given to paranoia and dreading loss of his North African outpost, had become obsessed with territory north of the Mediterranean out of concern that the Allies would gain a foothold in Sicily. With little confidence in Mussolini’s army, he grew determined to reinforce the Italian peninsula, even at the cost of pulling troops and matériel from the Eastern Front.

Malta was already in Allied hands; Sicily was the obvious next step, being more manageable and a bigger prize than Sardinia. But why did the Allies not sideline the whole area? Why not put their energies into the crucial cross-Channel invasion, already planned? The British argued that by continuing Mediterranean operations, the Allies would hasten Italy’s exit from the war, possibly prompting Turkey to join them. The Americans agreed, in part because large forces were already amassed in North Africa. And, despite frantic efforts at a naval buildup, the resources required for the D-Day invasion were incomplete.

In this worm’s-eye view of the Sicilian campaign, Holland insists on the importance of geography, topography, and other local conditions favoring the defender—heat, poverty, paucity of water, mosquitoes, bad or nonexistent roads, hills, ridges, narrow valleys , rocky formations, and villages like aeries. Dysentery disabled some troops; the numbers who fell victim to malaria surpassed those of the wounded or killed. Holland justifies this lengthy account by asserting that it has received meager coverage relative to its importance and its strategic lessons.

Holland’s narrative is well-organized. Thumbnail sketches of participants both Axis and Allied, some high-placed, provide an individual touch.

What is certainly annoying, however, is the book’s inferior language, connected, presumably, to his background in writing television documentaries. Apparently, he is not familiar with English subjunctives. Errors in sentence structure, verb agreement, and participle placement jump out. He misuses constantly the pluperfect tense, which must indicate action prior to that of the simple past. Colloquial barbarisms such as “a non-starter,” “dead cert,” “disorientating” are unacceptable. That World War II remains a popular topic does not justify their appearance in an otherwise-scholarly study. The publishers as well as Holland are at fault.

(Catharine Savage Brosman)

Leave a Reply